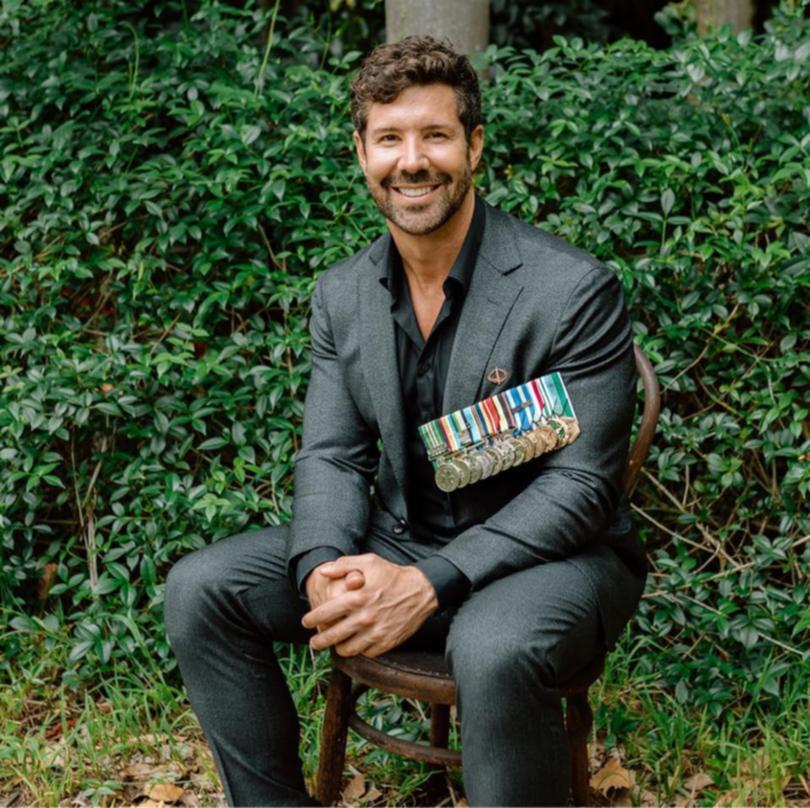

Special forces soldier Heston Russell explains why he kept his sexuality secret for 20 years

The former commando officer’s memoir reveals he used deception to prevent his soldiers discovering he was gay.

For any parent, there is a passage in ex-special forces officer Heston Russell’s autobiography that could break their heart.

When Russell was a young teenager, his father realised his son had used the family computer to search for images of a male actor in same-sex pornographic movies.

Over dinner, his father said: “Is this going to keep happening?”

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.“No Dad,” the ashamed boy said. “It’s never going to happen again. I promise.”

For the next two decades Russell kept up the lie, as he describes in Forging the Will to Fight. His career as an incognito gay man in one of the Army’s most aggressive units, the Sydney-based Second Commando Regiment, is a powerful reminder of the pressure many non-heterosexual people feel to hide their sexuality at work.

Soldier, leader, athlete

The life of Australia’s first known gay commando may also be an inspiration, and a warning, for all.

Russell was a terrific soldier, a great athlete and a fine leader. He fought for his country, was falsely accused of a war crime, considered suicide, and emerged as a celebrity whose every misstep is covered by the press. His life is a complicated mess.

“For a long time I’ve struggled with this feeling that I don’t fit into this world,” he writes in the book. “I realise that I haven’t yet found my place and have allowed the discomfort of this feeling, and my constant struggle to find meaningful connection with people, to take over too much of me.”

The story feels like Russell’s sense of separation may have been driven by his sexuality. As a young officer he used sex with women as camouflage for his attraction to men. He created fake dating profiles to find one-off sexual partners, pretending to be a high school sports teacher.

When Russell arrived in Afghanistan, where he led 30 commandos, his bedroom’s walls were covered by photos of naked or partially naked women.

To avoid suspicion, he left them up.

Mardi gras and defence

The defence forces have long ended any formal discrimination based on sexual preference. The Department of Defence has participated in Sydney’s Mardi Gras since 2013, an involvement celebrated by the RSL.

In the 2000s, Russell worried being gay could cost him a security clearance, which was necessary to be a special forces officer. Perhaps more importantly, he wanted to be judged for his professional performance, not who had sex with.

Russell is the only special forces veteran publicly revealed as gay, a fact that became hard to hide when a media outlet reported in 2021 he had used the OnlyFans website to generate income from men who found him attractive while working for a veterans’ charity.

Some colleagues may have suspected the truth. When he began his first job in the commandos, leading an anti-terrorist unit in Sydney, a much older non-commissioned officer said: “Maybe you’ll be the first gay platoon commander? Who knows? It’s a new army. Just be good at your job.”

In trouble

Russell’s military experience was not perfect. In Afghanistan he was told off for killing a Taliban fighter with a $200,000 Javelin missile, which he fired personally. His commander said he should have called in a non-Australian fighter jet to drop bombs on the enemy, which Russell estimated would have cost around $1 million.

In his last week in uniform, he was criticised by a war crimes investigation led by NSW Supreme Court judge Paul Brereton for firing warning shots near suspected Taliban fighters to stop them running away so they could be arrested. Australian soldiers are taught to only use their guns to kill.

After leaving the Army, instead of being celebrated as a LGTBQ pioneer, the ABC reported he participated the execution of a prisoner in 2012. Federal Court judge Michael Lee found the allegations untrue and awarded him $400,000 and his legal costs.

Last September, Channel 7’s Spotlight revealed the ABC had added gunshots sounds to video footage of commandos on a mission in Afghanistan. The public broadcaster apologised for the mistake. Now trying to build a career as a public speaker, Russell is campaigning for an independent inquiry into the ABC’s reporting standards.

Looking for a mentor

The fight over his reputation has pushed Russell’s sexuality into the background, but his memoir explains how it forced him to spend most of his life hiding his identity.

“The hardest part for me in the whole journey was not ever having another gay special forces person to be mentor,” he said this week.

In hindsight, Russell believes he made the right decision. Military culture requires the individual to subjugate themselves to a group. In communities like Sydney’s gay scene, which Russell belong to today, individuality is celebrated.

There were practical problems too. Homosexuality is banned across most of the Middle East.

“It’s very difficult to be the first of your kind, and that is what the whole journey is about,” Russell said.

“Me coming out being gay might have made me feel better personally, but could potentially have detracted from mission effectiveness.”

Once a soldier, always the soldier.