Tasmanian tiger: Melbourne scientists team up with US biotech company to bring iconic animal back from extinction

The species has been gone for almost a century, but that might be about to change.

Last month, a US biotech and genetic engineering company worth billions of dollars announced it had brought back the long extinct dire wolf.

Featuring in works of popular culture for decades, including in the Game of Thrones novels and then later the hit TV show, dire wolves were bigger than the wolves we know today, with larger jaws and teeth.

In April, Dallas-based Colossal Biosciences said it had “de-extincted” the animal, which died out over 10,000 years ago, using ancient DNA, cloning and gene-editing technology to alter the genes of a grey wolf.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.The news caused a buzz of excitement within the science community and created a flurry of questions about how the technology worked.

Closer to home, scientists in Melbourne, led by Professor Andrew Pask, are on a journey towards a similar scientific breakthrough — this time resurrecting the infamous Tasmanian tiger.

With Colossal’s backing, Pask is confident we could see the animal roam the island again in the not-too-distant future.

What happened to the Tasmanian tiger?

Pask has always been enthralled by the Tasmanian tiger, also known as the thylacine, and has spearheaded efforts to bring back the animal for the past 25 years.

He currently leads a team of 40 at the University of Melbourne’s TIGRR (Thylacine Integrated Genomic Restoration Research) Lab which in 2022 partnered with Colossal to accelerate the process.

“They have a huge set-up, you know, they have hundreds of millions of US dollars to actually build these massive genetic engineering facilities and things that we don’t have here in Australia,” Pask told 7NEWS.com.au.

“So being able to partner with them on this project has actually been a massive game changer, and it’s really accelerated the time that we can get this stuff done.”

The last Tasmanian tiger died on September 7, 1936 at Hobart Zoo.

The species was completely driven to extinction by humans, with European settlers mistakenly blaming the deaths of their sheep on the animals.

“It probably wasn’t killing sheep, very rarely. It wasn’t its major food source,” Pask said.

“But because it looked like the European grey wolf, it looked like predators that had been problematic for farming practices where they came from.

“The thylacine was, unfortunately, the scapegoat.”

Despite many hopeful Tasmanians claiming to have seen the animal over the last seven decades, and Pask’s lab regularly sent ziplock bags filled with faeces that people claimed were from the Tasmanian tiger, it was never seen again.

But Pask is confident he and his team can change that — and this is how.

How is this actually possible?

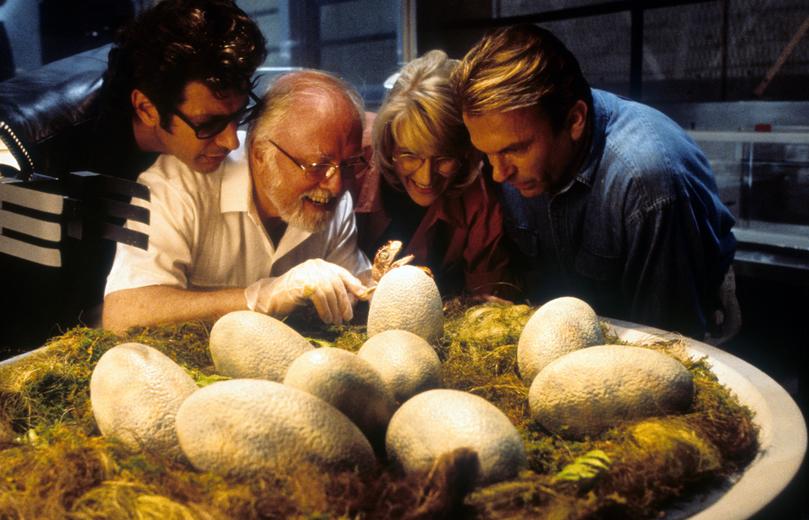

When we think of bringing back animals that have been wiped from the face of the earth, for most of us, our mind goes straight to Jurassic Park.

In the book, and film, scientists used DNA extracted from prehistoric insects preserved in amber to clone the dinosaurs.

Gaps in the DNA sequence were filled with reptilian, bird, or frog DNA.

What Pask and his team are doing to bring back the Tasmanian tiger is a little different, thankfully, as we all know what happened in Jurassic Park.

In 2018, Pask and his team published the first genome sequence of the Tasmanian tiger. A genome is the entire set of DNA instructions found in a cell.

This DNA was taken from a 108-year-old specimen preserved in alcohol at the Melbourne Museum.

“You cannot create life where there is none. You have to start with a living cell, and you need to edit that living cell to become your extinct animal,” Pask said.

“We can sequence the entire DNA of a thylacine, and we’ve done that end to end, every single bit of its three billion bases we know every single part.

“Once you’ve got that, you can say, what is the closest living relative?”

In comes the fat-tailed dunnart, a very small, very cute, mouselike marsupial.

The animal is the Tasmanian tiger’s closest living relative, with the two being over 99 per cent the same.

Unlike Jurassic Park, where scientists filled in the gaps of the frog or bird DNA to create a dinosaur, Pask and his team will go in and make edits in the fat-tailed dunnart’s DNA.

“We actually just make every single edit so that that final genome is a thylacine genome,” Pask said.

“The DNA from the last (Tasmanian tiger) that died, it’s broken up into hundreds of tiny little pieces.

“Though we know exactly what that code was, it’s in little bits now, rather than being in whole chromosomes, and so you have to put it back together.

“We can’t do that, but we can use an animal that has its chromosomes altogether.

“It’s easier to fix that 1 per cent than it is to try and rebuild the whole genome.”

While it’s not possible to rebuild a complete set of DNA from an extinct animal’s DNA, it might be possible one day in the future.

When Colossal announced it had brought back the dire wolf, some critics said the animal was mostly still a grey wolf.

This will not be the same as the animal that Pask and his team are trying to bring back.

“I think they made 20 edits across the whole (grey wolf’s genome), but if you were to completely rebuild it, like we do, into the thylacine again, it would be thousands and thousands of edits,” he said.

“For the animal we want to put back into Tasmania, it’s got to be complete. So, it’d be 100 per cent (a Tasmanian tiger).”

Pask and his team are up to the editing stage, which he says could take another 10 years.

In the future, when they’ve got to the stage of creating a Tasmanian tiger embryo, it will be implanted into a surrogate.

This surrogate will be a fat-tailed dunnart, and gestation can take up to 42 days.

Michelle Dracoulis, mayor of Derwent Valley Council in southern-central Tasmania and chair of the TIGRR Lab, travelled to Melbourne this week for Colossal Biosciences’ first annual Tasmanian Thylacine Advisory Committee summit.

She said Tasmanians are ready and waiting for the return of their beloved animal.

“The thylacine is a huge thing in Tasmania. Culturally, it’s part of the identity of the people down there,” she told 7NEWS.com.au.

“I think people would just be absolutely over the moon (if it was) out there again, because they dream of it. People think they hear it. People think they see footprints on the beach. It’s never gone away.”

Dracoulis said the tiger’s return would be vital from both a tourism and environmental perspective in Tasmania.

“We’re right at the edge of the world. It’s nearly pristine parts, and the fact we’ve taken this apex predator out, protecting that moving forward, especially when the world is changing so much, is vitally important,” she said.

Pask said what drives his work is the moral obligation he feels towards bringing back an animal that humans were responsible for destroying.

If the technology is available, and it is, then humans have to try.

“It’s morally unjust (to) not put everything into trying to bring this species back,” Pask said.

“It’s just a matter of going, we owe it (not just) to this species, but to the ecosystem, to bring these animals back.

“I feel very passionate about that.”

Originally published on 7NEWS