Veteran Jason Crocker’s tragic death sparks calls for urgent reform

‘We became the enemy. Because we were trying to save him.’

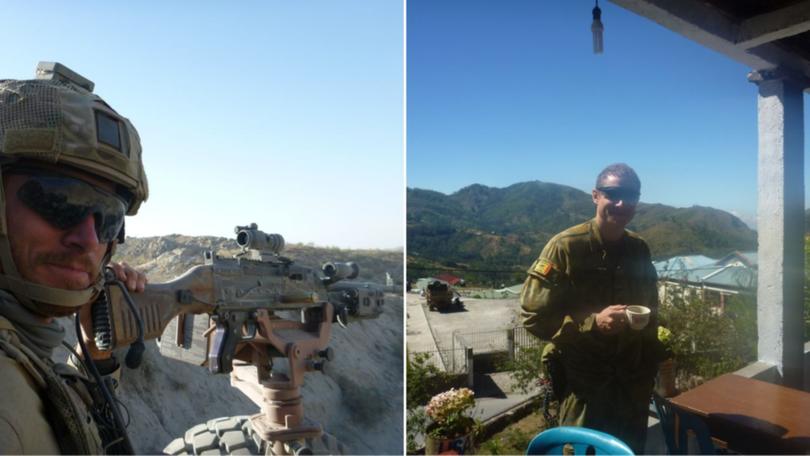

Jason Crocker was a veteran.

He served with the Australian Army and Navy.

He died homeless, alone, and in the grips of mental illness.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.As Australia honoured its fallen on Anzac Day this week, his daughter Claudia is preparing to bring her father home from a morgue in Blacktown, in Sydney’s west.

“My dad suffered immensely after leaving the military,” she told 7NEWS.com.au.

“He was never in his right mind to make decisions.”

While the nation paused to remember those lost in war, Jason Crocker’s story is a reminder of those who return and continue to struggle.

Recent data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare shows that suicide rates among Australian Defence Force (ADF) veterans are far higher than those lost in combat.

‘Support comes too late or not at all’

Ex-service members say the real fight begins when the uniform comes off.

From navigating broken systems to rebuilding their identity after discharge, veterans say the support they receive often comes too late or not at all.

Now, Queensland-based veterans are stepping up to demand real reform, sharing raw and personal stories of survival not just from battlefields overseas, but from the mental health system back home.

“Too many veterans leave service only to find themselves lost in a system that isn’t built for them,” said Brodie Moore, a former 6RAR soldier.

Moore is now CEO of Medilinks Access, a veteran-led service helping to navigate ADF members through the often overwhelming Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA) process.

‘It’s measured in lives’: Delays that cost veterans everything

“While reforms are underway and we have seen a significant reduction in claim backlogs, too many veterans are still waiting for services that should be immediate and accessible,” Moore told 7NEWS.com.au.

“Delay isn’t just measured in paperwork.

“It’s measured in lives.”

Claudia Crocker knows that reality first-hand.

Her father Jason served at Lavarack Barracks with 1RAR and later at Gallipoli Barracks in Enoggera with the Armoured Corps, before completing a year in the Navy.

A system not built for healing

After his discharge, he struggled with addiction and mental illness.

Claudia said her father was diagnosed with schizophrenia and substance use disorders, recognised by the DVA, but lacked support.

“Veterans are handed compensation and pensions, but without real help, it just enables the addictions,” she said.

“They are handed money and most veterans I know or have heard of turn to substances to numb the pain.

“The older generation of men aren’t used to talking and mental health, so they turn to what they know.

“When people aren’t in their right minds, it’s hard for them to make decisions about what will benefit them.”

‘We became the enemy’: A family shut out while trying to help

Claudia and her family tried to step in. They reached out to DVA. They contacted police. She even attempted to file a missing person report. Each time, they were turned away.

Between 2001 and 2018, data shows more than a quarter of all ADF suicides occurred in Queensland — a stark reminder that the state sits at the heart of a national crisis.

Moore said support often comes too late or not at all.

“Over 45 per cent of veterans struggle to adjust to civilian life,” he told 7NEWS.com.au.

“We’ve made progress, but the system is still far too complex.

“We need coordinated, veteran-led pathways that deliver timely mental health care, not months of red tape.”

His colleague, Michael Albrecht, who served in both infantry and intelligence for 11 years, says many veterans don’t even know what help they’re entitled to.

“Mental health challenges don’t always surface the day someone takes off the uniform.

“Often, it’s months or even years later—after the structure fades, the identity shifts, and the sense of purpose starts to erode.”

Despite the government’s recent passing of the VETS Act, which aims to improve the transition process for veterans into civilian life and streamline access to services, veteran advocates say it’s only a first step.

“Trust is the biggest barrier in veteran care, which is why peer-led organisations like Medilinks work so well - because we’ve walked the same path,” Albrecht explained.

“That shared understanding breaks down stigma, makes space for honesty, and builds bridges where institutions often can’t.”

For Claudia, this was the kind of support her father desperately needed — but never found.

Jason spent his final years disconnected from his family in Redcliffe, north of Brisbane, living between shelters and the streets.

Claudia says his condition worsened so severely that he began to push away the people trying to help him.

“We became the enemy,” she said.

“Because we were trying to save him.”

By early January, Claudia and her siblings were desperately trying to find their father.

Her younger brother, who is just 19, was posting on community pages in New South Wales asking if anyone had seen Jason.

“We were about to fly down to where he was last known to be to physically look for him and get him help,” Claudia said.

“But while we were making plans, he had already passed.

“It’s devastating, and I’d hate to think this has happened to any other family because no one deserves this.”

The family learned of his death too late.

Police knew his name and had informed DVA in January.

But no one told Claudia and her family, she said.

“The sergeant said to my mother, ‘What difference would it make?’” Claudia recalled.

“The difference is, he would already be home with his family, where he belongs, and not sitting in a morgue for four months, cold and alone.”

And that’s what Salute for Service aims to prevent.

Healing beyond policy: Why veterans say connection is key

For former Australian Army Private Marc Diplock, who now leads the veteran focused charity Salute for Service, recovery doesn’t always start with policy.

Sometimes it starts with connection.

“Leaving the military isn’t just about changing jobs — it’s leaving behind a tight-knit community, a shared purpose, and a sense of belonging that’s hard to find elsewhere,” he told 7NEWS.com.au.

“That unwavering trust, that knowledge that someone always has your back — that’s mateship.

“At Salute for Service, we’re here to help keep that spirit alive.”

He said many Australians only see veterans as either heroes or broken people.

“But real life is rarely that black and white,” Diplock said.

“The sudden loss of structure and purpose can trigger mental health challenges, but it doesn’t mean they’re broken.

“It just means they need the same compassion, respect, and support we’d want for anyone navigating a major life shift.“

For Paul ‘Warlord’ Warren, a former 1RAR soldier who once locked himself inside his house to avoid the world, healing didn’t begin with therapy.

It began with one conversation.

“Someone checked in on me — that’s all it took to start building trust again,” Warren said.

“Every veteran needs one person to believe in them.

“Then it’s about slowly finding your way back — to services, to community, to yourself.”

A month into his deployment, Warren lost his leg to an IED blast that also killed his mate.

Discharged from the Army, he faced a system that wasn’t built to support him — but he went on to captain Australia at the Invictus Games, wrote his memoir The Fighter, and was recognised with the Prime Minister’s Veteran Employment Award.

“Many of us come out with strong values, resilience, and a mindset that’s shaped by service and not just hardship,” Warren told 7NEWS.com.au.

“Psychologically, veterans are often incredibly capable: We’ve learned to solve problems under pressure, adapt quickly, and overcome adversity.

“That kind of experience belongs in the workforce and in our communities.

“If we shift the conversation from ‘what’s wrong with veterans’ to ‘what strengths do they bring’, we start creating space for them to thrive.“

As we pause to remember on Anzac day those who died in war, the veterans are asking the nation to look closer. Not just at the past, but at those still here. Still hurting. Still waiting for help.

For Claudia, Anzac Day is no longer only about the fallen in battle. It’s about those who came home, only to be left behind.

She launched a small fundraiser to help with the costs and to honour his memory.

This week, Claudia and her siblings are travelling to Blacktown to begin the process of bringing their father’s ashes home.

Not just to lay him to rest, but to make sure his story is heard.

If you or someone you know is struggling:

- Open Arms (for veterans and families): 1800 011 046

- Lifeline: 13 11 14

- Beyond Blue: 1300 22 4636

Originally published on 7NEWS