Ballarat’s dark past: ‘Women are living on edge’ after third suspected murder in less than three months

The death of Hannah McGuire is the third suspected murder in a matter of months to blight Ballarat — a city where people say they no longer feel safe.

Women feel unsafe on the streets of Ballarat as the Victorian city grapples with the deaths of three women in less than three months.

A rally decrying violence against women will take place at Ballarat train station on Friday after Hannah McGuire was allegedly murdered last week by her former partner Lachlan Young at the home they bought together in the town of Sebastopol, on Ballarat’s rural fringes.

Her body was found in the wreckage of a burnt out car in bushland less than a 15-minute drive from the home.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.

The death of Ms McGuire, a popular 23-year-old from the nearby town of Clunes where her family owns the local pub, came after two other recent deadly incidents. There is also a legacy of unsolved women’s murders over the past decades.

On February 16, police believe Rebecca Young’s partner, Ian Butler, who has links to outlaw motorcycle gangs, stabbed her to death at their home in Sebastopol before taking his own life. Two of mother-of-five Ms Young’s children were present during the suspected murder-suicide.

Just weeks earlier, on February 4, Ballarat mother-of-three Samantha Murphy disappeared after going for a run. Patrick Stephenson, the son of former AFL player Orren Stephenson, has been charged over her murder.

Rally organiser Sissy Austin said women no longer felt safe on Ballarat’s streets, but added that violence against women was a national crisis.

“Women are living on eggshells, living on edge,” she wrote on the online event page.

“Putting on the runners and going for a run feels like risk-taking behaviour; it is not and we shouldn’t be feeling like this. It is not normal for our beautiful bushlands to become known as a place where men’s violence is perpetrated on our bodies.”

Ms Austin told The Nightly that violence was peppered throughout the history of Ballarat, including the bloody battle of the Eureka Stockade and the legacy of the Ballarat orphanage, which housed more than 4000 children over the course of its operation between 1865 and 1980.

A 2002 lawsuit brought by 14 former wards of the orphanage made claims of physical and sexual abuse in the 1960s.

“I think that there’s been an issue of violence for quite some time in Ballarat, that hasn’t been talked about,” Ms Austin said.

“Like Ballarat is a very over-institutionalised regional town to start with and there’s a lot of poverty as well in Ballarat that needs to be addressed.”

The median weekly household income in Ballarat is $1429, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, compared with $1759 for Victoria.

Rates of domestic and family violence are higher than in the rest of Victoria, according to data from the Crime Statistics Agency.

There were 2200 reports of family violence in Ballarat in the year to December 2023, an increase of 3.9 per cent on the previous year. There was a 2 per cent increase across Victoria in the same period.

In that same period, almost three times as many female family members (1617) were affected by violence — almost 70 per cent at the hands of an intimate partner — as the 580 males recorded by police.

The most common forms of violence recorded by police at reported incidents in Ballarat include verbal abuse (44.1 per cent), emotional abuse (30.3 per cent) and physical abuse (11.3 per cent).

Yet, of the 2200 incidents of family violence in Ballarat last year, police only issued protective Family Violence Safety Notices less than 9 per cent of the time. That figure lags well below Statewide FVSN rates, with police across Victoria issuing them in 12.3 per cent of instances.

Ballarat mayor Des Hudson admitted the spotlight was on Ballarat for all the wrong reasons. He told The Nightly that it was understandable some felt unsafe after the spate of tragedies, residents were horrified by the alleged crimes.

“The type of behaviour that we saw (by) the individuals allegedly who have committed those actions is not OK, and certainly not something that we stand for in Ballarat,” he said.

“In fact, most of us would be absolutely disgusted and outraged by that.”

Ballarat is a city that is grappling with a dark past, the trauma from which still lingers in a population of about 115,000.

The Royal Commission into Institutional Child Sexual Abuse in 2017 found a culture of secrecy and catastrophic failings by the Catholic Diocese of Ballarat.

The city was also the domain of notorious paedophile priest Gerald Ridsdale, possibly the worst abuser of children ever caught in Australia.

Ballarat haunted by unsolved murders

Ballarat is haunted by the unsolved murders of several women.

In 1987, 70-year-old grandmother Kathleen Severino was found beaten to death inside her bedroom. A $1 million reward remains for information that can help catch her killer.

In 1991, the body of nurse Nina Nicholson was found on the back porch of her home. She had suffered fatal head injuries.

In 1998, the body of Tracy Howard was found dumped on Clarkes Hill Road, her clothes scattered along the ground.

Howard, whose de facto partner had links to a motorcycle club, was last seen leaving Cheers Night Club in Ballarat.

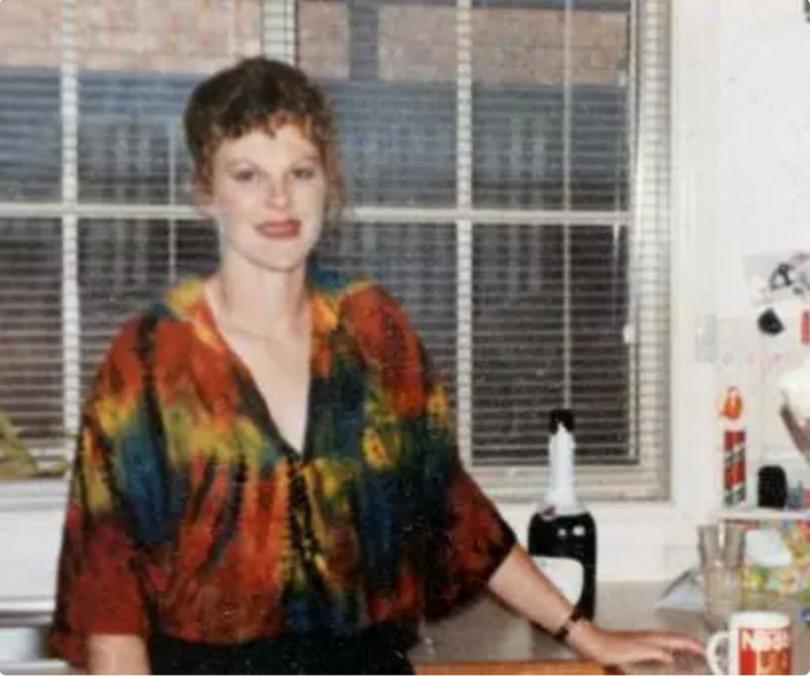

And, on July 6, 1999, the body of Belinda Williams was found by bushwalkers on Mount Buninyong Access Road.

An autopsy later revealed she had been strangled.