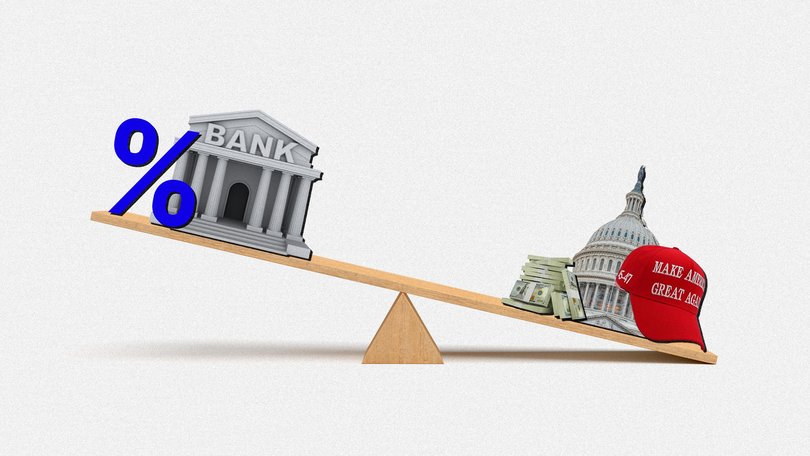

Donald Trump keeps messing with our interest rate

How Donald Trump’s ‘big, beautiful’ tax bill is impacting Aussie housing prices

Donald Trump’s “big, beautiful” tax bill is starting to look ugly.

After a period of relative exuberance following the 90-day tariff pause, Wall Street got the jitters again, dumping shares and pushing the Dow Jones down 1.9 per cent and the S&P 500 down 1.6 per cent.

Equity investors are being spooked by their more influential cousins: the bond traders.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Those investors, who represent $US140 trillion ($217 trillion) in global savings, don’t like what they see in US spending and are pushing up interest rates on long-term 10- and 30-year US Treasuries.

The White House is trying to extend the tax cuts of the previous Trump administration through US Congress. That would reduce tax revenue by $US4.1t over the next ten years, according to the non-partisan Tax Foundation, at a time when US deficits will soar to $US36t and well above 100 per cent of GDP. In effect, the US will be borrowing money to fund tax concessions.

All of this largesse was supposed to be paid for by tariffs - increasingly unlikely to raise anywhere near as much as hoped - and a cut in government spending.

DOGE, the Department of Government Efficiency, seems to increasingly be in the doghouse, with Elon Musk on the weekend telling a business forum that it has no power to mandate cuts. So far, the promised $US2t in savings is a paltry $US170b.

Last week, Moody’s ratings agency downgraded the United States’ creditworthiness and bond markets have responded pushing 30 year interest rates to 5 per cent.

“The market is basically saying, ‘look, we haven’t had a surplus since Bill Clinton and there is no end in sight to the deficits that we see,” said Christian Baylis, chief investment officer at Fortlake Asset Management and a former economist at the Reserve Bank

“In that case the US is a riskier prospect now because of its inability or lack of willingness to right the trends in fiscal spending. And the bond market is saying we need to charge you more for that additional risk.”

The bond market isn’t just worried about rising deficits, it’s also watching the inflationary impact of tax-cut-driven economic stimulus.

Government spendathon

Unfortunately, while the US is exploring new levels of profligacy, there aren’t all that many places for bond investors to hide.

Thanks to Mr Trump’s withdrawal from the global rules-based order, countries have decided they will have to spend far more on self-sufficiency.

Germany is a case in point, announcing an exemption from its “debt brake” rule for defence spending above 1 per cent of GDP, an increase in the borrowing cap for federal states from 0 per cent to 0.35 per cent of GDP, and, at the centre of it all, a new infrastructure investment fund valued at €500 billion.

Extrapolate that across the world, where nations feel they have no choice but to increase their own domestic production base, meaning less efficient industry and higher prices in the event of tariffs, or their own military for fear of a breakdown of Pax Americana.

Put that together and you have both a lift in global inflation and deficit-financed government spending.

Corporate spendathon

It’s not just governments going hell for leather on the cash burn.

As Westpac’s Luci Ellis points out, corporates are doing it too, primarily on the potentially transformative power of technology.

Hundreds of billions of dollars are pouring into the construction of energy-hungry data centres, driven by surging demand for artificial intelligence. This boom also brings a relentless need to reinvest in fresh banks of chips every year.

Westpac has already noted the impact of this trend in Australia’s capital expenditure figures. But there’s another notable shift underway: a growing share of this expenditure is going toward so-called intangibles, particularly software.

These technologies depreciate far faster than traditional manufacturing equipment. Where industrial machinery once lasted two decades, data centre infrastructure may need replacing in as little as two and a half years, demanding continuous and significant capital investment.

The promised land of the AI revolution will be another competitor for capital.

Australian rates can’t escape

For the bond market, all of this new indebtedness is feeling riskier and riskier and as a result there is this upward trajectory for long term interest rates.

For the Reserve Bank, that is a problem, Mr Baylis said, because Australian interest rates are highly correlated with US ones.

“Central banks will not be able to cut as deeply as they used to, because most governments are spending like drunken sailors. If all of these governments started printing fiscal surpluses, that would put downward pressure on interest rates, and that would allow the RBA to cut through that neutral level of, say, 3 per cent to 3.1 per cent.

“Basically, it means we’re going to have much higher levels of interest rates than people have been used to over the last few years,” he said.

Government spending back home is exacerbating the problem, with budget deficits well into the next decade and a pipeline of growing spending for an ageing population.

“I think the market is just ultimately saying we’re sick of it. No government is really doing anything without spending, and the bond market’s saying you guys need to wake up to yourself, because we’re not going to keep financing you into perpetuity at low rates if you actually don’t start to make some changes,” Mr Baylis said.

“There’s always this dog ate my homework-type excuses as to why they can’t fix it which means as the cost of debt goes higher and the interest bill goes a lot higher, it becomes a bit of a vicious circle.”

The housing impact

If you think this is just some treasury mathematics, think again. Interest rates are inversely correlated to house prices, and the market is saying longer term, those interest rates need to go up.

Australian banks borrow in international markets, so more expensive debt there means higher rates here, or a reduced ability to follow the RBA’s cuts down.

For mortgage holders looking for a bit more repayment relief, watch what US Congress is doing.