Best Australian Yarn 2023: Grey Paint by Josh Lowe

The Best Australian Yarn 2023: An emotive story by Josh Low about a young man who returns to his narrowed-minded home town and the hard-bitten father who refused to accept his teenage son was different.

I grew up watching this town devour its residents.

For some, it was instant: here one day, gone the next.

Others were chewed down slowly as the years rolled by.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Smiles melted into pursed lips, laughter faded into wheezy cigarette-scented coughs, and youthful faces withered into leathery frowns that lingered at the bar. This place would eat and eat until all that was left were the bones of people I used to know.

Yet, no one else ever noticed. Nobody wanted to see that we were as trapped here as the sugarcane that proliferated around us. With our roots sunk deep into the earth, we’d helplessly await the day we’d be cut down and fed to the beast. Knowing but not knowing alienated me, and I think my parents always knew, but chose to ignore the obvious. It felt as though acknowledging what this place was, and what I was, would be the end of us all.

My mother once said,

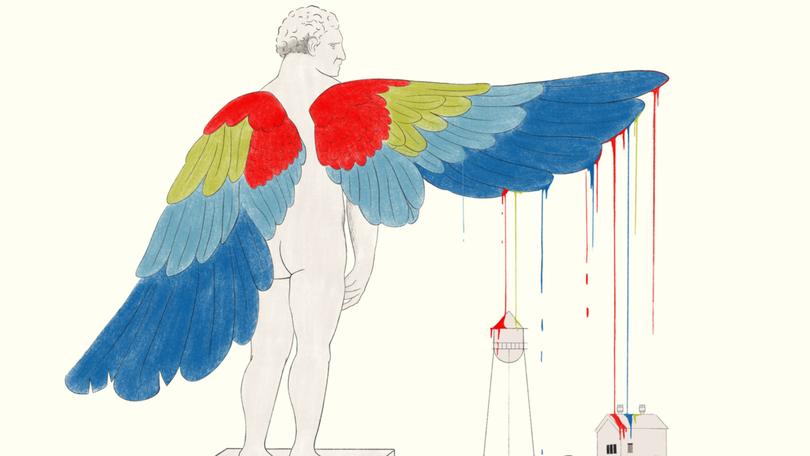

“Such are the troubles of a parrot raised amongst pigeons.”

I never truly understood what she meant by this, but figured, based on the tone in which she’d said it, that I was the parrot in her personalised proverb. I know she meant no harm by it; her nature was too gentle to hide razors in her words. Still, the problem with being a parrot in a town full of pigeons was that it drew attention, and the problem with drawing attention in a place like this was that it got you eaten alive.

Shame was this town’s favourite flavour, and perhaps this is what my mother had always meant to say, but the truth remained the same regardless.

Colourful feathers don’t fare well in monochrome towns.

So, I painted them grey.

I feel it breathe me in, dragging me forward like a hungry animal as I drive down the dusty road. Blurs of sugarcane stream by the windows, gently swaying as if to wave and welcome me back. There’s a sharp pull to my left and I wrestle the wheel to keep me on the road. Only a few kilometres into town and this place is already snapping at my throat, shaking my car like a bird caught in the bite of a rabid dog.

The car stops.

I find myself staring at the flat tyre for far longer than the few seconds it should have taken to diagnose the problem. The part of me that never wanted to come back here is begging to fly away, to take this as a warning and get out.

I don’t.

Instead, I find myself listening retrospectively to a lecture from my father. At thirteen, he had me changing a tyre in the old shed beside our house for, in his opinion at least, that was what men did. I remember feeling his stern gaze on my back as I panicked to follow instructions.

Make sure you’re on firm ground, handbrake on.

I suppose, in his mind, he was teaching me how to survive in this place, giving me more grey paint to lather over my colours. There are two things fathers are expected to do: teach their children the ways of the world, and show them they’re loved unconditionally.

He managed to do one of those.

Remove the hubcap, then loosen the nuts.

I drop the wheel brace to the dirt when I’m done with it and use my fingers to check the tightness.

Find the jacking point, then raise the car. DON’T put yourself underneath it.

I jump backwards, picturing a graphic image of bloody legs sticking out from underneath my collapsed Subaru. This town would feast on my remains if it got the chance. My breathing becomes shallow and sweat beads from my skin, but the lesson continues.

Remove the nuts, then the flat tyre… Put the spare on, then the nuts. Lower, tighten, check, replace the hubcap.

When I’d first learned how to do this, my father’s silence let me know I hadn’t messed it up. My mother’s quiet applause let me know I’d done it well. She was the perfect counterbalance for his abrupt and clinical demeanour. She radiated sanguinity and, despite her tranquil nature, had a fierce power about her. You’d see it in the slightest of moments. A gentle hand placed on my father’s shoulder could sway conversations in entirely different directions, directions which I’m sure were the ones she’d always intended, and ones that were usually in my favour.

I heard them arguing one night, their sharp whispers seeping through the crack below my bedroom door; fragments of a conversation I didn’t want to hear. My father thought I was too soft and that some hard labour at the next crush was the solution.

“He’s thirteen, he should be out doing things with his friends, not working his childhood away,” my mother protested.

“He doesn’t have any friends,” came my father’s voice, followed by a stern hush from my mother.

That stopped me. He wasn’t wrong. People say the best way to make friends is to just be yourself, but I was buried so far beneath layers of grey paint that authenticity was impossible. Not having friends in a predatory town was like laying yourself down on a chopping board and begging to be eaten. The irony of it was that being a parrot did the same, so no matter what I did, this place was going to eat me. All because I was born with those damned coloured feathers.

I did make one friend eventually though, Payton. He moved here with his parents in the ninth grade from the city. It was our mutual hate for this town that sealed the deal, but I suppose he won the title by default given the lack of competition. Each afternoon, we’d trek down the dusty road from the bus stop, kicking rocks and making grand plans to one day get out of this place.

Most kids our age had already surrendered themselves to the town’s hungry jaws. People born here scarcely left, not because they didn’t want to, but because they never felt they could. They were born to girls too young to be mothers and raised in schools too underfunded to be useful. They dropped out early, became slaves to the sugar mill, and the cycle would begin again with a new generation of victims. All the while, this town devoured the hopes they once held so high.

My mother was one of those victims. I think, in her own way, she knew what this town was and was desperate for me to escape its grasp. She’d leave university pamphlets on my dresser and sign me up for after school tutoring, all in the hope that it’d give me a chance to escape this place in the years that followed. My father was never onboard with it though. He’d protest the idea at every chance he got, always reminding me that crushing season was upon us and that it’d need to be all-hands-on-deck if we were going to get through all of the cane.

The farm was all he knew, and a life of monotonous labour was the only distraction he had. If he stopped he’d be eaten alive. My mother was the perfect remedy though. She’d wield her magic words to help him see life through a different lens, and he’d loosen his grip on me.

She was always a slim woman, built so delicately that one could easily imagine her floating away in the afternoon breeze. Sometimes I wonder if she once had colourful feathers like mine, and if they’d just faded with years of entrapment. It should have been obvious to me that this town was slowly chewing away at her, and perhaps if she’d been of a larger stature to begin with, I would have noticed before it was too late, but as the months rolled by, her bright eyes yellowed and she grew thinner and thinner until one day this town swallowed her up entirely and she was gone forever.

Her passing broke me, but it completely destroyed my father. His stubbornness metastasised, and he fell into a negative spiral of booze and resentment as the town sucked the joy from his bones. He became one of the leathery faces at the pub with the sad eyes and haggard breaths.

Each afternoon, I’d pray to find a changed man when I walked back through the front door, but I’d always be let down by the stench of spilt booze and unwashed clothes. So, I kept my distance for a while, spending my time at my only friend’s house. Payton’s mother was happy enough to have me, she never asked about my father, but she knew what this place had done to him. Payton, on the other hand, was less subtle about his disapproval.

“Tell your old man to get his crap together,” he’d say. “Or I’m gonna have a word with him.”

He was joking of course, but Payton was big for the sixteen-year-old he was at the time. I’m sure, if he had ever ‘had a word’ with my father, he probably would have been rather intimidated, not that he’d have let on.

I laughed his comment off, feeling slightly uncomfortable with the banter. He was as boisterous as they came, but gentle at heart. Like a big sulphur-crested cockatoo amongst a town of pigeons, his splash of yellow blended into the monochrome, and perhaps that’s why he became so popular. I always wondered why he chose to befriend me, the guy with weird paint-covered feathers, when making friends came so naturally to him. Deep down though, I think I always knew the reason, and I only wish I’d been brave enough to see it.

In the last year of school, we spent almost every hour together, enduring the endless study days and spending the weekends planning our escape from this place. As I look back on it now, it was obvious that this town was slowly biting down on him, like it had my mother. It was in the distracted moments, where he’d get lost in conversations, and in the forced jokes he’d make when asked where his mind had wandered to. He was right there with me every day, until one day he wasn’t, and he never would be again.

His mother told me the news.

Death was not a stranger to me, but this was something worse. This town ate my mother, but Payton had fed himself to it, and I couldn’t help but wonder if there had been more to him than white and yellow. I lay in bed rotting away for what felt like weeks. It’s selfish, I know, but after a while I found myself praying that his passing would be the wake up call my father needed, that he’d see what this town was doing to us and sober up.

He didn’t.

Tensions rose in the weeks that followed until one day, drunk on adrenaline and grief, I told my father the truth. I washed the grey paint away and showed him, with trembling words and shifting eyes, what he was always too afraid to see.

I kept my distance while I spoke, hovering by the front door of the house but still close enough to the couch on which he sat to hear his bitter response.

“If that’s what you really are,” he said coldly, his gaze fixed sternly on the glass of whisky in his hand, “then fly away.”

So, that’s what I did. I took to the skies two weeks later, and I’ve been in flight ever since.

With the flat in the boot, I slam the car door behind me, leaving the memories outside by the sugarcane, and drive further into the belly of the beast from which I came.

It’s been almost a decade, but the house looks the same as I remember it. A dishevelled Queenslander in need of fresh paint stares down at me as I drag my feet up the veranda’s steps, legs shaking.

I’d always thought that escaping this town would mean I’d finally be free, but it turns out this place comes with you when you go. Like a parasite, it latches onto you, draining every drop of life that it can. I can feel it breathing down my neck now, preparing to strike.

This is my last chance to cut myself free.

I raise a shaky hand to the door and knock.

No response.

I don’t know for sure that he still lives here, but if the old man is as stubborn as I remember, there’s no way he would have sold this place. I pause for a moment, smooth down my feathers, and gather the courage to knock again.

Nothing.

I breathe a breath of frustrated relief and retreat down the steps, my legs eagerly carrying me back towards the safety of the car. Every beat of my heart feels like it could be the last.

The sugarcane beside the house rustles angrily in the breeze. Cockatoos screech in the distance, and I prepare to surrender myself to the jaws of the beast. Something moves in the corner of my eye, and an old man emerges from the shed by the side of the house.

This place has not been kind to him.

A few strands of wispy grey hair cling to his head like cotton, and his sun-kissed skin is wrinkled into leathery folds. His clothes are caked with so much dirt that it’s difficult to tell what colour they once were. Despite all of this though, he still looks better than he’s looked in years because he’s holding a spanner in his hand and not a bottle.

As we cautiously step closer to one another, I can see his eyes are damp with sorrow and regret. He’s staring at me with suspended disbelief, as though he’s afraid this town will snap me up at any moment, like it did my mother and dearest friend. His mouth is trembling, and a series of unintelligible choked sobs are spurling out.

I don’t blame him though, there are no words for what he must be feeling now.

My wings are shaking uncontrollably, preparing to fly me up into the clouds and away from this place at the slightest whiff of disapproval, but I stand my ground and hold on.

I hold on because, in this moment, I realise I’ve found what I’ve spent my life searching for. Finally, deep within my father’s gaze, and in the warmth of his gesture as he reaches for a hug, I find a sense of pride.

I grew up watching this town devour its residents, painting myself sombre and cowering in its shadow. But I can tell now that this place will never be able to eat me, not because I’m of the same feather as most, but because for the first time in my life, I’m wearing these colours without shame.

Originally published as Best Australian Yarn: Grey Paint by Josh Lowe