The Saturday Night Live machine grinds on as it celebrates 50th birthday

Like Sally O’Malley, Molly Shannon’s spry, bouffant-sporting quinquagenarian, Saturday Night Live is 50 years old, limber for its age and a little too proud of itself.

It isn’t hard to understand why.

In 1975, Lorne Michaels’s brash experiment was supposed to garner NBC’s Saturday late-night slot more viewers than Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show reruns — while channelling the counterculture, modernising the variety show and luring a generation of disaffected young people back to TV.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.It did all that and more.

Saturday Night Live gave TV a little rock-and-roll cachet partly by making fun of it.

The show lampooned commercials and presidents and TV executives.

It launched squadrons of memorable characters, dozens of stars, commandeered NBC’s late-night lineup and influenced several generations of American comedy.

As the world takes stock of the scrappy, anti-establishment underdog that became a gigantic (and respectable, even stodgy) comedy institution, two things are clear.

The first is that any grand theory of American humour is doomed to fail; there is still, even after all these years, no reliable formula for a successful SNL sketch.

The second is that the show has been around so long that genuine novelty is all but impossible.

This last is as true for sketch premises as it is for behind-the-scenes histories.

SNL being an oft-memorialised show, it sometimes feels as if everything worth saying about it has been said.

It’s a truism by now that Michaels, the show’s creator, is a popcorn-loving cipher known for lavishing attention on some cast members while others wait five hours for an audience.

Everyone working on the show is miserable.

The production schedule is murderously stressful by design, and the output is comedically uneven but — from a television production standpoint — almost miraculously competent.

Performers describe living through a breakout moment, when a sketch is really working, as the best feeling in the world.

And no matter how bad the backbiting and internecine competition gets, the experience of surviving it all tends to bind cast members old and new.

Pop culture aficionados will recognise that those conditions sound like a decent premise for a TV show.

It’s not a coincidence that two of the more successful projects Saturday Night Live inspired, Jim Henson’s The Muppet Show and Tina Fey’s 30 Rock, focus on the backstage antics and giant egos with which the stressed-out showrunner of an SNL-type variety show must contend.

Both were driven by a vague but firm consensus that the show must go on, even if no one quite remembers why.

Both established that the onstage material the public sees is the least interesting stuff happening in the studio.

From the beginning, one thing that defined Saturday Night Live as a phenomenon was that stories about the show constantly threatened to overshadow interest in the show.

SNL became a hit, spawning imitators and setting the conversation among young people.

It was also an industry fable — a rupture in a business (and a genre) people thought they understood.

And a star-maker that inspired interest well beyond what happened on-screen.

By the fourth season, which began in fall 1978, the original cast had gone from nobodies to celebrities fighting off paparazzi and fans.

John Belushi was on the cover of Newsweek; Gilda Radner was on the cover of People. Fans couldn’t read enough about the cast or the show’s bizarre backstage culture.

In Saturday Night: A Backstage History of Saturday Night Live, Doug Hill and Jeff Weingrad note that the New York Post even did a story (with photos!) on the show’s cook.

There were always, and continue to be, juicy rumours about feuding stars —like Dana Carvey and Mike Myers or Bill Murray and Chevy Chase.

The show’s fandom includes a certain curiosity about everyone concerned — up to and including Michaels.

Rightly so. Saturday Night Live famously launched whole franchises and careers.

Eleven films have featured SNL characters, and dozens more have been created by or starred SNL alums like Eddie Murphy, Chase, Kristin Wiig, Amy Poehler, Myers, Murray, Adam Sandler, Chris Farley and Will Ferrell.

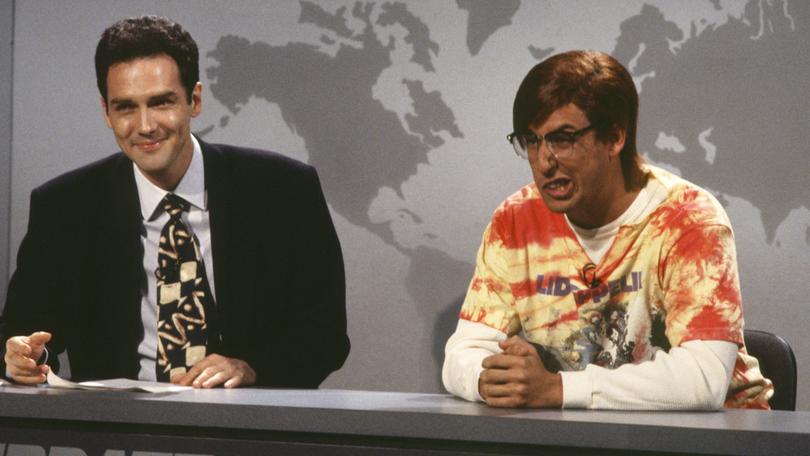

Former cast members who got their own TV shows include Dana Carvey (The Dana Carvey Show), Norm Macdonald (Norm Macdonald Has a Show), Fey (30 Rock), Bill Hader (Barry), Colin Quinn (Tough Crowd With Colin Quinn) and Jason Sudeikis (Ted Lasso).

Maya Rudolph and Martin Short briefly hosted a variety show together, called Maya & Marty.

Former SNL writers have fared better still.

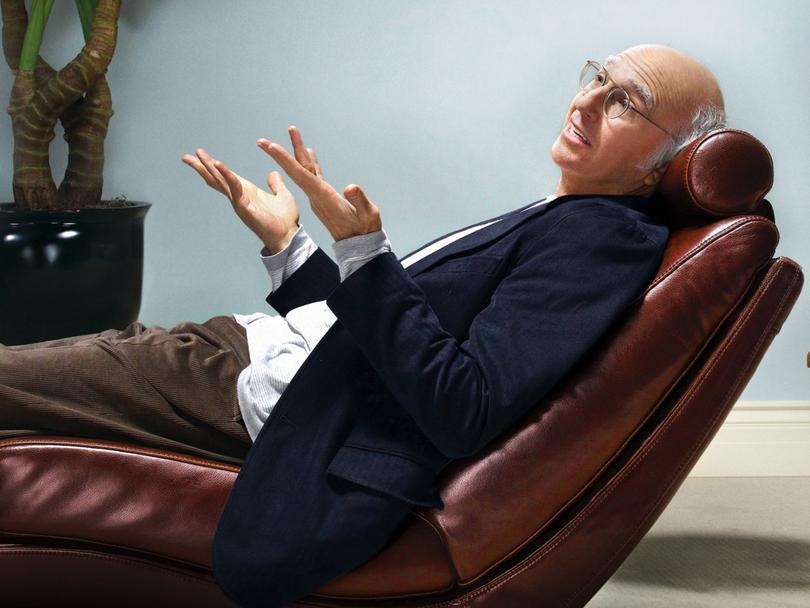

Besides TV host and podcaster Conan O’Brien, that list includes Larry David (Seinfeld, Curb Your Enthusiasm), John Mulaney (Everybody’s in L.A.), Anna Drezen (Girls5Eva), David Mandel (Veep), Bonnie and Terry Turner (3rd Rock From the Sun), Mike Schur (The Good Place, Brooklyn Nine-Nine), Simon Rich (Man Seeking Woman), Emily Spivey (Up All Night), Dave Attell (Insomniac With Dave Attell) and Adam McKay, whose long list of TV projects includes Eastbound and Down (which he co-produced with fellow SNL alum Will Ferrell), The Chris Gethard Show and Succession.

Chris Kelly and Sarah Schneider created The Other Two, starring Shannon; Tim Robinson made the well-regarded I Think You Should Leave; and Bob Odenkirk, who won Emmys for his writing on Saturday Night Live, is a respected dramatic actor.

But the most pleasing SNL stories tend to be the ones fans string together themselves.

Did you know, for instance, that in the best Night at the Roxbury sketch — the 1996 one where host Jim Carrey (who auditioned for SNL and didn’t get it) joins Ferrell and Chris Kattan, and they crash a wedding — the bride is Nancy Walls, who had recently married a guy named Steve Carell?

Ten years later, Carell would parody the Roxbury sketch as Michael Scott in The Office (and Walls would play his girlfriend, Carol).

Those are the sorts of cross-pollinations the show has made possible.

This particular instance also drives home — because Michael Scott and Andy Bernard have notoriously bad taste — that the sketch I loved as a kid is a little creepier and uglier than I remembered.

It hits differently now that I’m older.

That’s part of the SNL story, too.

For all its beloved recurrent sketches — like Phil Hartman’s Unfrozen Caveman Lawyer, Vanessa Bayer’s Totino’s trilogy and Ferrell’s Celebrity Jeopardy — the show is also an absurd, sometimes accidental and not especially flattering record of the evolving national ID.

Humour being not just subjective but also deeply context-dependent, the show’s hit rate is historically contingent.

Viewers born after Gerald Ford’s presidency might intellectually appreciate Chase’s impression, but it’ll never do for them what it did for viewers who watched in real time.

Even classics like Murphy’s Gumby and Ana Gasteyer and Shannon’s Delicious Dish depend on at least a little prior knowledge.

Era-specific jokes sometimes land like transmissions from an alien civilisation.

“Huh,” I remember thinking when I first saw Samurai Hotel and the famous cheeseburger sketch.

“This is what people used to find hilarious.”

But then I watched the Elliott Gould Killer Bees sketch — and sent it to everyone I know.

Because anniversaries are supposed to celebrate history, they are always slightly awkward (history, by its nature, being a mixed bag).

It’s old news that showbiz stories reveal a particular era’s predilections and blind spots.

SNL yarns are no exception: Nora Dunn was pronounced “difficult” for refusing to perform in the episode hosted by controversial comedian Andrew Dice Clay; Janeane Garofalo was sidelined for calling sketches sexist (writer Fred Wolf, in Tom Shales and James Andrew Miller’s book Live From New York, called her “an infection on that show”).

Male performers got more leeway, more chances and more credit.

Belushi’s awful conduct on- and off-set tended to be folded into the show’s “rock-and-roll” ethos.

That contemporary assessments try to adjust for some of those early-period errors doesn’t mean they always work.

It’s understandable, for instance, that stories about Belushi’s hostility to the show’s female writers (including Anne Beatts and Rosie Shuster, Michaels’s then-wife) tend to focus on, well, Belushi: “He felt as though it was his duty to sabotage pieces written by women,” SNL alum and comedian Jane Curtin has said; he believed “women should not be there”.

It seems to be less widely known that Michaels knew this and was aware of an ugly, Cyrano de Bergerac-style workaround that credited men with the women’s work.

“He didn’t do pieces that Anne or Rosie wrote, so somebody would have to say that a guy had written it,” Michaels said in Live From New York.

It’s gratifying, for related reasons, to see the 2024 film Saturday Night acknowledge Shuster’s role in the show’s early, improbable success.

Shuster created the memorable The Nerds sketches (featuring Murray, Radner and Curtin as Todd, Lisa and Lisa’s mother), the Bees, and Radner’s most famous character, Roseanne Roseannadanna.

But the way the film uses SNL lore — like Shuster’s liaison with Dan Aykroyd while married to Michaels — sometimes feels misleading.

Saturday Night uses the affair to illustrate the couple’s unconventional marriage and portray Shuster as the cooler, more dominant partner, an impression aided by the casting (the actress playing Shuster is several years older than the actor playing Michaels).

That feels like a misrepresentation; according to Shuster, she met Michaels when he “followed (her) home from school” when she was 14.

Shuster was born in 1950; Michaels was born in 1944.

They married in 1967, when Shuster was 17.

Retrospectives should, ideally, centre some of those less-than-flattering stories, too: The way Tom Schiller found out he was fired, for instance (people were packing up his office).

The way certain performers were underused, like Garofalo, Julia Louis-Dreyfus, Joan Cusack and Chris Rock.

How Black cast members from Garrett Morris to Danitra Vance to Rock to Tracy Morgan to Damon Wayans struggled with their place (and with the writing) on the show.

There are also, of course, the sunnier industry stories with which most of us are familiar.

Two of the show’s bigger stars of the past decade, Bowen Yang and Kate McKinnon, are queer.

Much has been written about how Shannon, Cheri Oteri, Rachel Dratch and Gasteyer helped usher in a culture more receptive to female performers and writers — along with Rudolph, Fey, Poehler, and later Wiig, Bayer, Nasim Pedrad, Aidy Bryant, Leslie Jones, Cecily Strong, Melissa Villaseñor, Ego Nwodim, Sarah Sherman and McKinnon.

And about how Seth Meyers and Fey — in their respective roles as SNL head writers — fostered a less dysfunctional workplace environment.

But the biggest SNL story everyone got wrong, throughout its long and varied run, concerned its imminent cancellation.

Saturday Night Live has been (reportedly) dying for as long as it has been alive.

The show briefly became a critical darling before a cycle of approval and backlash set in that continues to this day.

Five decades into its run, the 17th floor of 30 Rockefeller Plaza in New York City could be wallpapered in headlines announcing its likely cancellation.

And reviews dissecting its decline.

And letters excoriating it for joining the mainstream ethos it once defied.

SNL kept rising from the almost-dead, and each resurrection was followed by a fresh onslaught of claims that the show has lost its relevance, its grip, its edge or its mind.

Sometimes it had.

The sixth season was indeed rough, since most of the show’s stars, writers and Michaels himself had decamped.

The 11th season — when he returned in 1985, was arguably even weirder.

Season 20, which aired in 1994-95, is often cited as the show’s worst for reasons enumerated in a notorious New York Magazine feature about how messy the show had gotten, and ended with the departures of Adam Sandler and Chris Farley, among others.

Consensus on any of these points — or on which were the top 10 sketches or who were the best cast members — is impossible.

Mostly, Saturday Night Live is a demographic Rorschach test.

The best era tends to be the one the speaker saw when they were 12 and weren’t really supposed to be watching.

The best Weekend Update was whichever one was on when you had started to care a little (but not too much) about the news.

It’s almost poetic, therefore, that 50 years after it began, the show’s challenge — despite all the intervening change, and its evolution from irreverent upstart to corporate behemoth — remains the same: How can SNL reach young viewers who think linear TV is lame?

The task, now, requires targeting a demographic that never experienced “appointment television” and finds network television so irrelevant they might not even have a way to access it.

Historically, the show has leaned pretty hard on the “live” aspect.

SNL cannily harnessed the suspense inherent in live broadcasting by subjecting its cast to the kind of public stress we now associate with reality TV.

It’s a thrill to watch what a group of impossibly talented comedians with high standards, different sensibilities and no time can put together while working with a famous host who has to master the whole process in less than a week.

It’s a doomed mission. This just is not how you make something great.

“I want to do something well,” Gasteyer said of her pivot to theatre after her stint at SNL — no doubt channelling the sentiments of dozens of SNL perfectionists whose job it was to churn out something passable.

But watching them try is fun. The show’s recipe amounts, in other words, to a kind of special pleading.

Audiences know to expect more mediocrity than excellence.

But there’s always the possibility of something transcendent breaking through — or of an equally spectacular on-air failure.

That rush can sometimes push performers into accessing something that wasn’t there even during dress rehearsal (like Christopher Walken’s affect in More Cowbell).

Or into flubbing a line so badly that no one quite recovers.

Or breaking.

It’s to SNL’s credit that great sketches happen far more often than they should.

But “liveness,” as such, isn’t much of a draw anymore, especially for young folks, who tend to watch clips online.

The sketch-comedy show feels like it’s trying to adjust.

It features more prerecorded stuff these days, fewer recurring characters and better political impressions than political commentary.

James Austin Johnson, who plays President Donald Trump, might be the finest impressionist in SNL history at the moment that matters least.

SNL once had enough political relevance that it was suggested, rightly or wrongly, that Fey’s impression of veep candidate Sarah Palin tanked John McCain’s presidential campaign, and that Michaels’s controversial decision to let Trump host sanitised him the businessman enough to secure his 2016 victory.

No one would make a similar argument about 2024.

Still, I won’t make the mistake of predicting the end of SNL.

I will say I’m not sure what SNL is doing, edge-wise.

I’m not sure the show knows, either.

The recent Peacock documentary SNL50: Beyond Saturday Night Live features former cast members watching their audition tapes.

Touching though it is to view these established celebrities seeing themselves back when they were untested — and reflect on how far they’ve come — it’s hard to overlook how much misery the show seems to have caused so many of the funny people who’ve made it.

That’s not everyone’s experience.

Sandler, for instance, called it “creatively the best time of my life,” and Fey has firmly defended the show’s competitive aspect.

On Conan O’Brien’s podcast, Wiig observed, “there’s something about that place where you just need to be a little uncomfortable”.

Others are less sanguine.

Rock called SNL a “weird, Waspy world”.

Mandel recalls “a bunker mentality”.

“It literally was the worst year of my life,” Chris Elliott said.

Julia Sweeney said that by the end of her run, “I felt like I would have scrubbed toilets with a toothbrush rather than come back to that show.”

Myers called it “a cross between ‘Love Boat’ and ‘Das Boot’.”

The conditions haven’t changed as much as one might hope; in the Peacock documentary, one of the current writers, while grateful for the job, says that his mental health has never been worse.

Maybe that’s just the price of success.

Or maybe the lesson is simply that context matters.

As the show gears up to celebrate five remarkable decades in the business — and the politician the show mocked and invited to host tries to take control of the nation’s cultural institutions — keep an eye out for sketches that used to strike you as hilarious.

Some will be evergreen.

Others will feel strange or upsetting or just plain sad.

I don’t just mean stuff that might offend contemporary sensibilities.

I mean stuff like Schiller’s 1977 short film for the show, Don’t Look Back in Anger, in which Belushi visits the graves of his SNL friends, unaware that he’ll be the first to die, a mere five years later.

Or Love Is a Dream, that oddly earnest short from 1988 starring Jan Hooks and Phil Hartman.

Ten years later, Hartman was killed by his wife, and Hooks, who died at age 57 of cancer, never got to become the kind of sentimental old woman she plays in the sketch.

There’s an adage that comedy equals tragedy plus time. The reverse might be equally true: Comedy, plus time, gets dark.

(c) 2025 , The Washington Post