The New York Times: A Hollywood heavyweight is Joe Biden’s secret weapon against Donald Trump

Few have dived headfirst into the President’s reelection campaign more thoroughly than Jeffrey Katzenberg. The longtime Hollywood mogul known for ‘The Lion King’ and ‘Shrek,’ among many others.

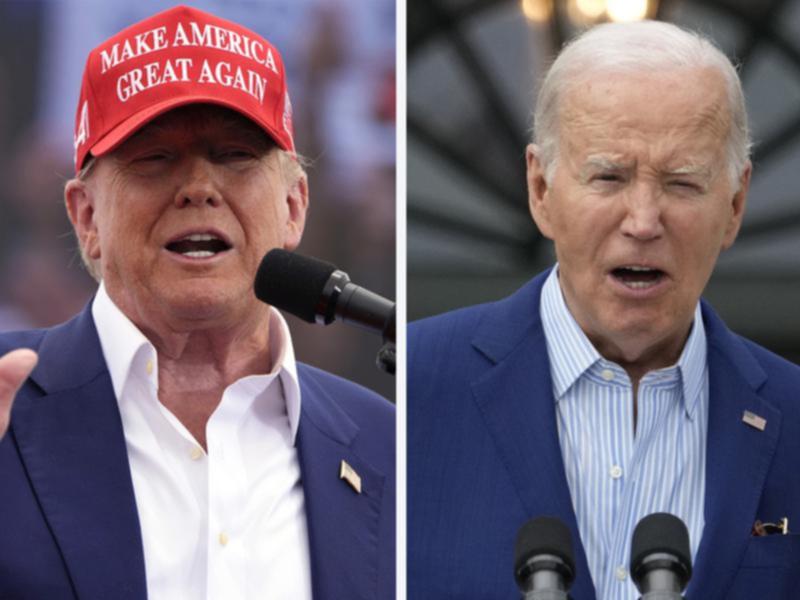

WASHINGTON — When President Joe Biden made clear last year that he was planning to run for another term, some important Democratic contributors expressed doubt. He was too old, they feared. He was not up to another four years.

It fell to Jeffrey Katzenberg to tell them they were wrong. When some still did not believe him, Katzenberg challenged them to come to Washington and find out for themselves — then arranged to bring the dubious donors to the White House to sit down with the octogenarian president to convince them he was still sharp enough.

“He was like, ‘Trust me. And if you don’t trust me, trust, but verify. Come with me and see for yourself and engage with the president,’” California Gov. Gavin Newsom, a longtime ally of Katzenberg’s, recounted in an interview. “And he started doing that in a consistent way.” In the end, Newsom added, “He really was instrumental in getting people off the sidelines and getting them to dive headfirst in this campaign.”

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Few have dived headfirst into the president’s reelection campaign more thoroughly than Katzenberg. The longtime Hollywood mogul known for “The Lion King” and “Shrek,” among many others, Katzenberg has been one of the most prolific cash generators for Democratic presidents for a generation. On Saturday night, he will bring Biden together with former President Barack Obama, George Clooney, Julia Roberts and Jimmy Kimmel for a star-studded fundraiser in Los Angeles, after the $26 million fundraiser at New York City’s Radio City Music Hall in March that he arranged with Obama and former President Bill Clinton.

Although Katzenberg has not solved Biden’s age problem by any means and Biden aides noted that some of those he brought to the White House did not need convincing, his efforts to validate the president with the well-heeled set have helped build a war chest that has been outpacing the Trump campaign. But he has gone far beyond his past political work, joining Biden’s campaign as co-chair and investing himself fully in the effort to defeat former President Donald Trump.

Katzenberg can be found in the halls of the West Wing offering advice and counsel. He was at Camp David the weekend before the State of the Union address, helping Biden prepare for his nationally televised speech. He pushes the campaign to tape reaction videos of the president for social media and connected Biden aides with writers to help come up with jokes for the president to deliver at the White House Correspondents’ Association dinner.

“He’s a true believer in the importance of this election,” said Rob Flaherty, deputy campaign manager. “He speaks about it in really existential terms. He talks about how this is what he wants to spend his time on and he can’t focus on anything else. He’s a really relentless guy.”

Biden speaks with Katzenberg several times a week, as do many of his advisers. “To the best of my knowledge, this guy doesn’t sleep,” said Jeffrey D. Zients, White House chief of staff, noting that he was speaking in a personal capacity, not in a campaign role. “He’s 24/7. That’s invaluable.”

He can be a handful, though. “He doesn’t take no for an answer,” said Rufus Gifford, the campaign’s finance chair. “He definitely has an opinion and argues it vociferously, which I appreciate.” The two talk so much, Gifford said, that “he calls us Batman and Robin. We argue about who’s Batman and who’s Robin.”

It is no real surprise that Democrats are happy to offer testimonials to Katzenberg. For years, he has been the party’s go-to guy to tap Hollywood money, raising millions of dollars for Clinton, Obama and others. It is, likewise, no surprise that skeptics wonder what’s in it for him. Big-dollar fundraisers usually want something, whether it be policy or perks. Katzenberg has plenty of business interests these days, mainly in the technology sector.

But if he has an ask, Democrats say he has not made it yet. “I never got a sense that there was any personal interest, if you know what I mean. Never. Never,” said Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass, who benefited from Katzenberg’s help in her 2022 election. “He’s not trying to be an ambassador. He’s not trying to have a Cabinet position.”

Trim and wiry, intense but amiable, Katzenberg at age 73 still exudes a kind of ambitious, animal energy as if he were one of his movie protagonists. He is famous around Hollywood and now Washington for rising at 5 a.m. and riding an exercise bicycle for 90 minutes while simultaneously reading four newspapers before taking as many as three breakfast meetings — and waffles or eggs-and-extra-crispy-bacon breakfasts, not the leafy California kind. “The guy eats like a horse and he doesn’t gain any weight,” his close friend Casey Wasserman, a sports, music and entertainment mogul, groused good-naturedly.

Katzenberg declined to give an interview for this story, but in public forums, he has described himself as a “super-triple-type-A” personality and a demanding boss who became famous for telling employees that if they did not come to work Saturday, they should not bother showing up Sunday. “Exceed expectations” is his two-word mantra.

“I’m not a bunter,” he said in an onstage interview at the Summit Palm Desert in California in 2022. “I’m not a base hitter. I’m not a runner. I only know one thing: My whole career has always been about ‘Swing for the fence.’” He has no patience for second best. “Show me a good loser — I’ll show you a loser,” he said.

Katzenberg grew up in New York’s Upper East Side, the son of a Wall Street stockbroker and an artist who sent him to Ethical Culture Fieldston School. He picked up a love of gambling from his father that got kicked him out of summer camp.

At loose ends, the teenager then went to work for Mayor John V. Lindsay, eventually becoming the mayor’s body man carrying his papers and bags of cash to pay for speech venues in the days before credit cards were more widely used. “That was my college degree,” said Katzenberg, who dropped out of New York University.

Ultimately, he went West and became an assistant to Barry Diller, a media tycoon, and worked his way into the film business, becoming close to Lew Wasserman, a longtime Hollywood power broker. “My grandfather handed him the baton,” said Casey Wasserman, now chair of the Los Angeles 2028 Summer Olympics. “He doesn’t play a lot of games. He’s really incredibly straight down the middle. What you see is what you get.”

First at Walt Disney Studios and then, after being pushed out in a power struggle, at DreamWorks, the firm he founded with Steven Spielberg and David Geffen, Katzenberg helped shepherd to the screen films including “Star Trek: The Motion Picture,” “Raiders of the Lost Ark,” “Good Morning, Vietnam,” “Pretty Woman” and “Dead Poets Society,” as well as animated classics such as “Aladdin,” “The Little Mermaid,” “Madagascar” and “Kung Fu Panda.” By his own count, he had a hand in 406 live-action movies, 41 animated movies, more than 85 television shows and five Broadway plays.

Not known for excessive self-doubt, he was brought low when his effort to build a streaming video app for short-form content with Meg Whitman, the former CEO of eBay, proved an embarrassing flop. Despite $1.75 billion in investment, their startup firm Quibi folded after barely six months, unable to find a market during COVID-19 against competitors such as TikTok. His technology investment firm, WndrCo (pronounced Wonder Company), however, just announced this month that it had raised another $460 million in venture capital funds.

Over the decades, Katzenberg indulged his interest in politics and became what Paul Begala, a longtime Democratic strategist, called “the greatest fundraiser alive.” Begala, a native Texan, noted that ranchers put a bell around the neck of a lead cow for the herd to follow. “Jeffrey Katzenberg is the Democratic Party’s bell cow,” he said.

Begala said Katzenberg was so fixated that he called on election night 2012 when Obama was declared the winner. “Who are we for in 2016?,” Katzenberg demanded. “I think it should be Hillary. We should get started.” Begala recalled protesting that he had not yet celebrated that night’s victory: “Jeffrey, I haven’t even had time to get drunk.”

But that means Katzenberg can get ahead of things. On Election Day 2016, when Hillary Clinton was expected to defeat Trump, Katzenberg met at the Waldorf Astoria New York with actor Alec Baldwin. The two were mapping out plans for a television comedy starring Baldwin as Trump in an alternative reality in which he had won the presidency.

Like many Democrats, Katzenberg nurses a visceral dislike of Trump. He has told associates that he met Trump in New York decades ago and thought even then that the real estate tycoon was entitled and rude. “He was a colossal” jerk “then and nothing has really changed,” he told an Axios-sponsored gathering in West Hollywood last month, using an expletive. Not that it stopped Katzenberg from making a guest appearance on “The Apprentice” with Trump in 2006.

Asked why he is so determined now to defeat Trump, Katzenberg often tells a story about a high school assignment to interview his European-born grandparents about where they were before World War II. He discovered that they did not believe Adolf Hitler posed a real danger during his rise. He tells associates that he does not want his grandchildren to ask what he was doing when his own country faced a similar test.

Trump also happens to fit into Katzenberg’s theory of politics and movies: He likes to quote Walt Disney saying that movies are only as good as their villains. Trump is much easier to present to voters as a villain than, say, John McCain or Mitt Romney were.

If Trump is Scar from “The Lion King,” Katzenberg sees Biden as Mufasa, the wise father-king. It may not be the best analogy — Scar kills Mufasa in a coup to take over the Pride Lands, and it falls to Mufasa’s son Simba to seek justice and topple the usurper.

But the point is that Katzenberg has been pushing the Biden team to think of the campaign as a story to tell. “He’s a good thought partner on how you bring the various elements together,” said Michael Tyler, campaign communications director, who estimates that he talks with Katzenberg several times a week. “How do you create a moment? How do you make sure it’s not a run-of-the-mill moment?”

That was why he was at Camp David before the State of the Union, sitting in Aspen Lodge along with Biden’s advisers. Katzenberg did not write or edit the speech, but he offered his thoughts about how to frame the narrative, along with pleas for brevity that were not entirely successful. He has argued that Biden should lean into the age issue, calling the president’s longevity “his superpower.”

Katzenberg is not a policy wonk, although lately he has been absorbed by the problem of homelessness in Los Angeles. He has pressed Bass on that issue and even flew to Sacramento, California, in a raging storm for a 15-minute meeting with Newsom to advocate for a more robust homeless policy before turning around to fly home.

None of that compares to his passion for the Biden campaign, though. Even his beneficiaries find it curious that he is so all-in on this campaign. “I’ve asked him in 10 different ways on 10 different days, ‘Why are you doing this?,’” Newsom recalled. “He looks at me cross-eyed and gets upset every time I ask him what are you after here.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

© 2024 The New York Times Company

Originally published on The New York Times