The New York Times: Remembering 1984, The Year Pop Stardom Got Supersized

THE NEW YORK TIMES: Forty years ago, the chemistry of pop stardom was irrevocably changed. The indelible albums of 1984 were turning-point releases, pivotal bits from acts decisively multiplying their impact.

Forty years ago, the chemistry of pop stardom was irrevocably changed. 1984 was an inflection point: a year of blockbuster albums, career quantum leaps, iconic poses and an enduring redefinition of what pop success could mean for performers — and would then demand from them — in the decades to come.

The indelible albums of 1984 were turning-point releases, Prince’s Purple Rain, Madonna’s Like a Virgin, Tina Turner’s Private Dancer, Bruce Springsteen’s Born in the USA and Van Halen’s 1984 among them.

They were pivotal statements from established acts who were decisively multiplying their impact.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Those blockbusters were propelled by an unlikely convergence of artistic impulses, advancing technology, commercial aspirations and popular taste, all shaped by the narrow portals of the pre-internet media landscape.

The eye-popping novelty of music videos, the dominance of major record labels and the cautious formats of radio stations still made for a limited mainstream rather than the infinitude of choices, niches, microgenres and personalized recommendation engines that the internet opened up. It was a peak moment of pop-music monoculture.

Listeners in the 1980s absorbed hits that felt like ubiquitous earworms: the fanfarelike synthesizer riff of “Born in the U.S.A.,” the saxophone cushioned by synthesizers in George Michael’s Careless Whisper, the drone and percussion and bawled vocals of Shout by Tears for Fears.

Younger generations have definitely heard and seen their repercussions, whether or not they’ve played the originals.

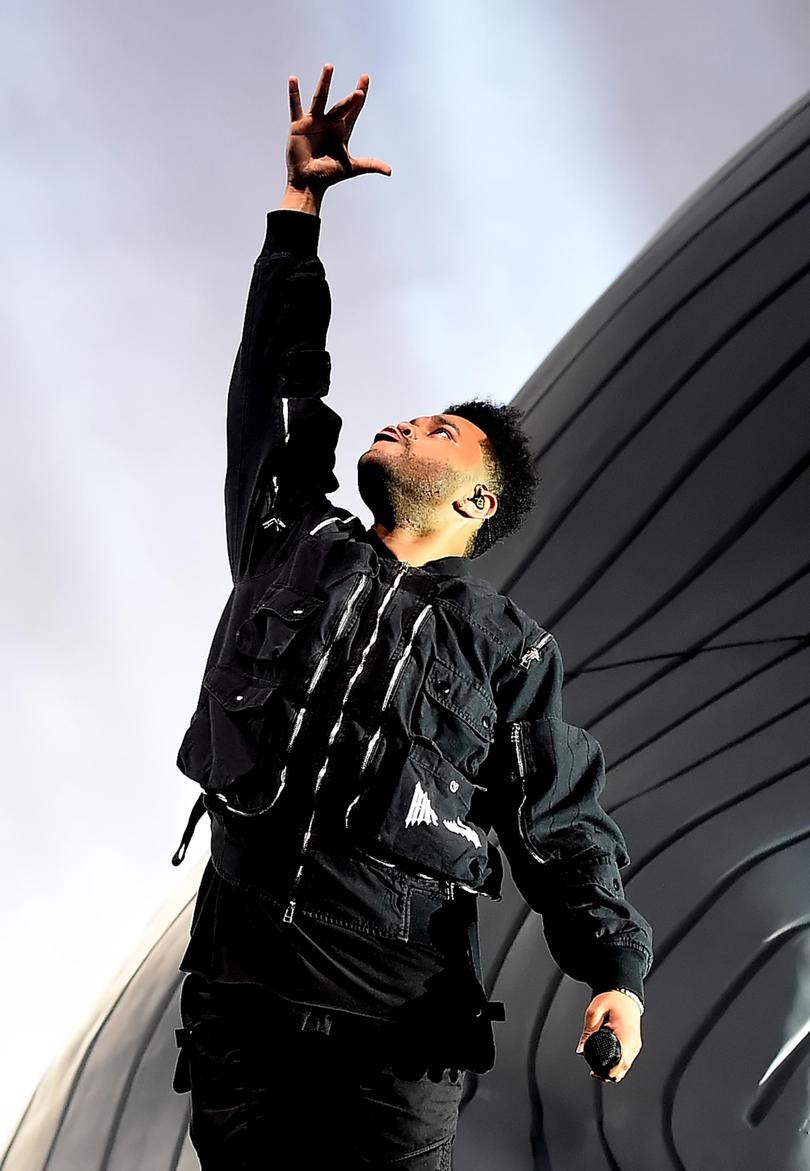

The sounds and lessons of 1984 have been durable and widely recycled by countless synthesizer-pumped 21st-century hitmakers, among them the Weeknd (Blinding Lights) and Sabrina Carpenter (Please Please Please).

But another major change came beyond the music: Ever since the mid-1980s, most musicians seeking a mass audience — millions of albums sold, arena and stadium tours — have been expected to titillate cameras as well as microphones.

Sound recordings and real-time concert performances would no longer be the full job description.

It became clear that a memorable video presence could elevate a performer from stardom to superstardom.

Visuals weren’t just for album covers and magazine photo shoots anymore; they became an essential element that could make or break an artist.

Flaunting its impact — and implicitly claiming credibility to rival the fuddy-duddy Grammy Awards — MTV presented its first Video Music Awards in 1984, making an immediate splash when Madonna rolled around the stage in a wedding gown and Boy Toy belt buckle as she performed Like a Virgin.

So why did everything fall into place in 1984? Mass-market ambitions were welcome in the mid-’80s.

Optimism, expansion and unabashed materialism were on the upswing after the sour end of the 1970s, which had spawned the low-budget, decentralized, street-level movements of punk, disco and hip-hop.

There were still DIY die-hards in the 1980s: Hardcore mosh pits proliferated in noncommercial spaces, and hip-hop was forging its infrastructure. (Run-D.M.C.’s debut album arrived in 1984.)

But the pendulum was swinging back toward corporate initiatives and blatant luxury. (Hollywood caught up by 1987, with Gordon Gekko’s pro-greed manifesto in Wall Street.)

In 1984, the United States was pulling out of the recession of President Ronald Reagan’s first years in office, with a recovery goosed by tax cuts and ballooning national debt; he would be reelected in a landslide in November.

Fashion promoted outsize, shoulder-padded silhouettes, brilliantly satirized by David Byrne’s giant onstage suit in Talking Heads’ 1984 concert film (and album) Stop Making Sense.

Hairstyles were chemically tortured into sci-fi-colored, gravity-defying configurations. The title of Wham!’s 1984 album spelled out both the strategy and the goal: Make It Big.

Yet even as commercial imperatives were kicking in, it was also a moment of artistic discovery for both seasoned hitmakers and savvy newcomers. They were testing and learning new methods to supersize their cultural impact.

Through the 1970s, the sound of pop had evolved to become ever more legible across arenas and giant clubs.

The simplified beat of disco filled dance floors, but even if it sounded repetitive, it was often played by a live rhythm section. The 1980s drew even more souped-up, mechanized productions from recording studios.

The arrival of CDs in 1982 allowed for newly expanded dynamic range, and musicians and producers learned quickly to exploit the openly artificial sounds of FM synthesizers and programmable drum machines.

Prince was fond of an early, expensive drum machine, the Linn LM-1, which socks out the beat of When Doves Cry.

The 1980s saw the introduction of affordable synthesizers with preset sounds and digital oscillators — which stayed in tune better than early analog ones — like the Yamaha DX7 digital synthesizer and the Roland Juno series.

Easily programmable drum machines like the LinnDrum and the Roland TR-808 (which became a hip-hop essential) also hit the market, and their sounds quickly found their way into the Top 10, leaping out of radio speakers.

Take on Me, the worldwide 1985 hit by a-ha, gets its crisp, popping beat from a LinnDrum, its hook from a Roland Juno-60 and some of its pearly keyboard tones from a DX7.

It wouldn’t be long before booming, overblown drum sounds — like the stop-start pounding in Kate Bush’s 1985 Hounds of Love — became a 1980s cliché; now, they’re an easy way to date the era’s recordings.

But by 1984, pop had acquired a permanent digital gloss. Hand-played, organic, real-time sounds would be a choice, even a renunciation, rather than a given.

Pop hooks would no longer just be sonic ones; they would be visual, too, as sound and video egged each other on. With a VCR, a star’s outfits and moves could be studied on repeat; choreography could become as familiar as a chorus.

Viral TikTok crazes have four decades of roots.

Scaling up meant honing new skills.

Fashion statements had long been part of rock stardom, from Little Richard’s pompadour, Elvis Presley’s gold lamé suit and James Brown’s capes to Kiss’ makeup, gender-bending glam-rock costumes, and the rips and safety pins of punk.

But the 1980s demanded a new level of spectacle.

The era welcomed artifice, even from musicians who would have been content to just stand there and sing.

Of course, Michael Jackson had shown the way.

He was already a star before he released Thriller in 1982 — first as the song-and-dance prodigy fronting the Jackson 5, and then as the grown-up, self-defining R&B innovator who announced his post-Motown emergence with Off the Wall in 1979.

But Thriller set all its own benchmarks.

With seven hit singles, it dominated the pop charts for more than a year; it was No. 1 until mid-April of 1984.

And it held that position because it married impeccable music to irresistible videos: Billie Jean, Beat It, Thriller.

Jackson broke down MTV’s unspoken but obvious color line, and he reaffirmed that his presence was no video trick when he moonwalked through Billie Jean onstage for the Motown 25 special in 1983.

Musicians learned to remake themselves as archetypes or cartoons.

In 1983, a savvy Cyndi Lauper arrived with herky-jerky moves and primary-colored costumes to announce Girls Just Want to Have Fun, while a Texas blues-and-boogie trio, ZZ Top, went pop with its album Eliminator, switching to metronomic rhythms and making a series of videos flaunting long beards, blond dancing women and a snazzy red car. Van Halen made hard rock look like comedy in videos that played up both David Lee Roth’s exaggerated leer and Eddie Van Halen’s boyish grin.

On the cover of Born in the USA, Springsteen claimed American-flag iconography with a red baseball cap, white T-shirt and blue jeans, even though the songs on the album were far from jingoistic about the state of the American dream.

Tina Turner redefined her solo career to make herself the voice of a bruised but powerfully resilient survivor.

And Prince’s Purple Rain built an entire movie around him, mythologising his character, the Kid, as a local musician struggling to make his mark, while every song demonstrated the scope of his talent.

Entertainment’s migration from the proscenium to the screen was underway well before the internet.

Even at concerts, audiences nurtured on video hits came to expect comparable production values onstage, an employment boon for choreographers, backup dancers, set designers and video directors, and an opportunity for small-voiced lip-syncers who could execute the right moves.

Big, accomplished voices — Whitney Houston, Bono, Alicia Keys, Adele, Beyoncé, Olivia Rodrigo — can still flourish, but they’re no longer mandatory.

The stars who were catapulted to new peaks in 1984 went on to lasting careers; even now, Springsteen and Madonna have stayed on the road.

Eventually, YouTube’s video on demand would break down MTV’s dominance, while streaming services would allow musicians and listeners to circumvent the gatekeepers of radio.

But the lessons of 1984 have lingered: Scale up, gloss up the sound and visuals, embrace the archetypal and never forget to play to the cameras.

Pop performers in the 21st century grew up on idols who could look good and sound larger than life while hitting their marks in Jumbotron-size close-ups.

They expect nothing less of themselves, and so do their fans.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

© 2024 The New York Times Company

Originally published on The New York Times