LINDSAY L GRAFF: One-third of shark species are at risk: Hollywood must wear part of the blame

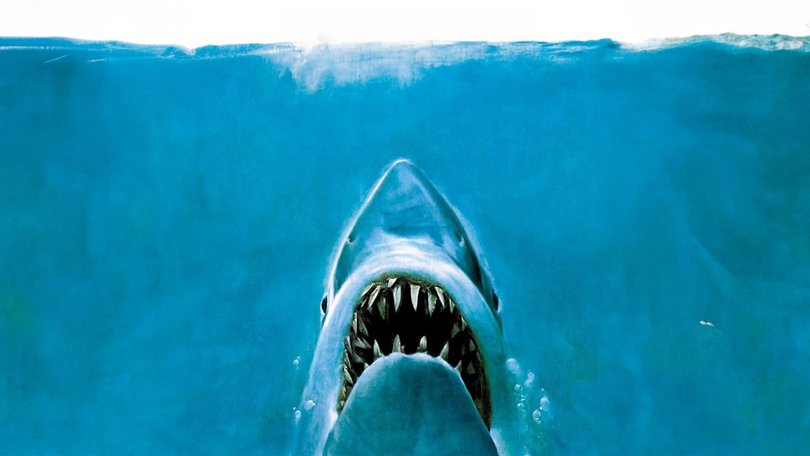

There are few summer traditions more predictable than turning sharks into profit. Fifty years ago, on June 20, 1975, Jaws established the template for the modern-day blockbuster, combining mass marketing and high-concept thrills that all but guarantee mega box-office returns. But the film’s lasting power lies in how it transformed a relatively obscure marine predator into a cultural icon and villain that could be used for financial gain.

Before 1975, sharks managed to lead inconspicuous existences that belied their ecological importance. Fear of sharks wasn’t born with Jaws: Isolated incidents had already stirred public alarm in coastal communities. It was easy to scale local anxiety into global panic.

Transforming sharks into predatory monsters leverages the primal unease humans experience when we’re reminded of our natural place within the food web. In a single release, Jaws distilled a subclass of hundreds of species, small and large, down to the singular, misleading moniker of “man-eater”. After 1975, sharks became unforgettable — and extremely profitable. But half a century after Jaws, the truth is clear: humans are far deadlier to these animals than they are to us. Each year, we kill an estimated 100 million sharks, largely due to overfishing, where they are caught intentionally for finning or incidentally as by-catch.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Sharks were the perfect monsters for an economy built on entertainment and fear — not facts. Their capability of causing traumatic harm to humans (47 people were bitten by sharks last year in unprovoked attacks) lent enough validity for the “man-eating” label to stick, irrespective of the fact that the vast majority of shark species feed primarily on fish, squid, invertebrates and planktonic organisms. It was far easier to sell society on sharks’ evil tendencies than it was to face the reality that you’re statistically more likely to be killed by a grass-eating hippopotamus.

The lack of research on and public understanding about sharks in the 1970s allowed them to become whatever Hollywood imagined. This fact can be heard in the remorse of Jaws author Peter Benchley, who, after an encounter with a great white shark while diving in the Bahamas, penned an essay with his famous line: “I couldn’t write Jaws today. The extensive new knowledge of sharks would make it impossible for me to create, in good conscience, a villain of the magnitude and malignity of the original.”

Before science could dispel the myths, sharks had been cemented in the public’s eye. The immense success of “Jaws” sparked a wave of films, including sequels: Jaws 2 (1978), Jaws 3-D (1983) and Jaws: The Revenge (1987). Hollywood’s interest exploded. Television networks followed suit. Discovery Channel aired the first Shark Week in July 1988, and it has since become an annual rite of passage.

Shark Week leaned heavily into sensationalised storytelling of shark attacks and shark bite re-enactments. It provided a space for viewers to face their growing galeophobia, however misguided, without leaving the comfort and safety of their living rooms. Today, Shark Week is the longest-running cable television programming event in history.

As the scientific and public perception of sharks matured, driven by advances in marine science and public education, media channels adapted their content; sensationalised fearmongering was replaced with conservation-focused storytelling, and shark behaviour was allowed to extend beyond the overused verbiage of “lurking” and “stalking”.

Even as Hollywood maintained its fascination with the man-eater — not least of all in the series of six (six!) Sharknado movies — National Geographic launched its own week of shark-focused TV in 2012, SharkFest, developing it into the multi-week TV event that it is today. SharkFest is marketed as a science-based, educational alternative to Discovery Channel’s Shark Week, but the platform remained grounded in the same logic: that sharks are media assets designed to generate viewership.

There remains an uneven balance between episodes of science and spectacle — each meant to appease an audience viewing these animals through a different lens. (Even the popular TV show Shark Tank, which has nothing to do with these cartilaginous fishes, is meant to evoke in viewers the sense of business-focused, man-eating investors.)

Recently, the commodification of sharks has reached digital platforms, such as Instagram and TikTok, where sharks fuel personal branding and ego. Platforms are flooded with influencers who disguise sharks as subjects of scientific curiosity and conservation, when in reality they are used as props to gain followers, views and personal clout. We are spammed with content from people recording themselves unsafely interacting with wild animals and sensationalising shark encounters to feed a performative image of bravery or connection with nature. They are exploiting these animals like those before them did on our movie and TV screens, reducing 450 million years of evolution to a tool for engagement and sponsorships.

Humans intentionally kill sharks for profit, selling their fins for shark fin soup or mounting them as trophies. Consequently, over one-third of shark and ray species are now threatened with global extinction. By contrast, between 2019 and 2023, there were just 64 unprovoked shark attacks globally, including six fatalities, per year on average. Most attacks occur when swimmers or surfers are mistaken for prey, such as seals.

Sharks are important and worthy of conservation and research, and not because they generate profit. Without sharks, marine ecosystems can unravel, leading to population booms of prey species, degradation of habitats and a loss of biodiversity. Sharks matter — not for what they give us, but for what they are.

Lindsay L Graff is a shark researcher and PhD candidate in marine biology at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth