THE WASHINGTON POST: Why we need fashion magazine editors more than ever

THE WASHINGTON POST: Michael M. Grynbaum captures the longing for an earlier, more sparkly zeitgeist in “Empire of the Elite: Inside Condé Nast, the Media Dynasty That Reshaped America.”

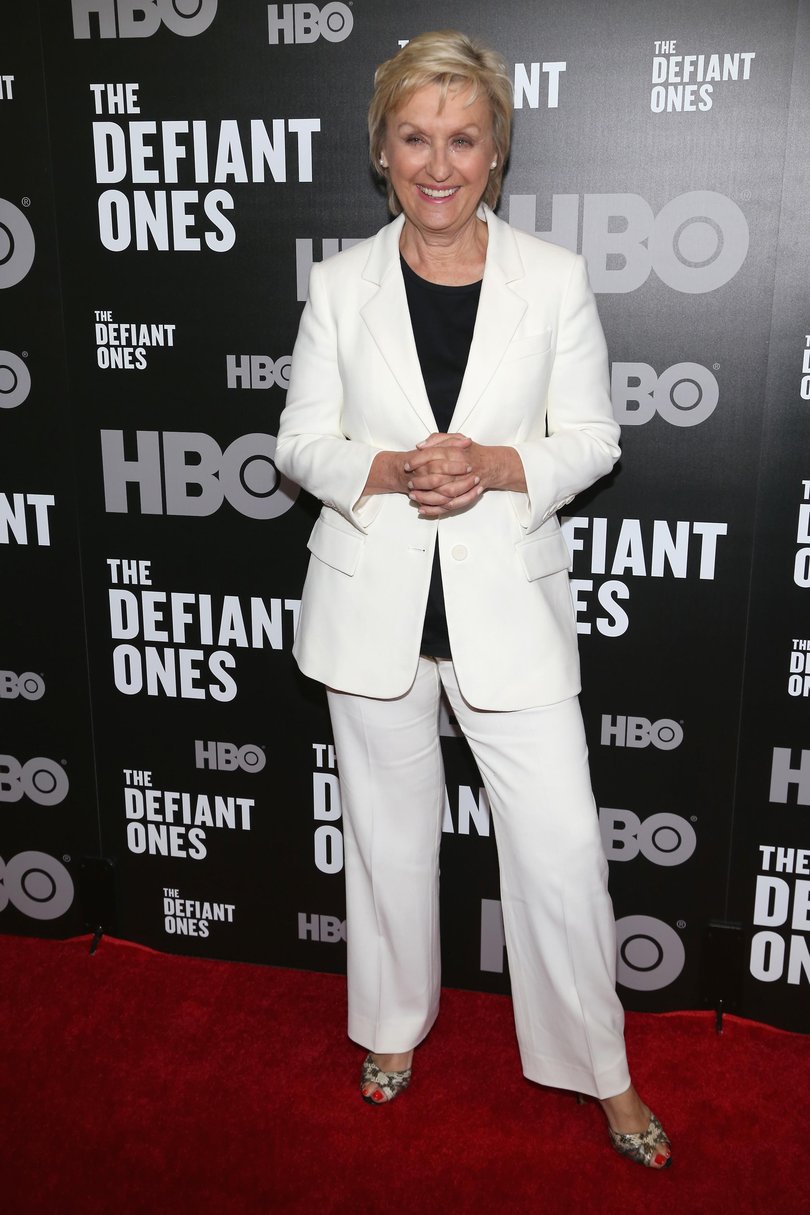

It’s 2025 and veteran Vanity Fair and New Yorker editor Tina Brown is on Substack, opining on private jets and Jeffrey Epstein conspiracy theories.

Former Vanity Fair editor Graydon Carter recently published a memoir about his magazine world heyday, and did a jolly round of interviews with all the new media talkers: fashion podcasts, food podcasts and sound bytes for Interview.

And multiple generations of fashion fanatics are pouring one out — and by “one,” I mean a splash of nonfat oat milk matcha — for Anna Wintour’s (pseudo-)retirement from the day-to-day operations of American Vogue.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Soon the 21st-century decline of the fashion media landscape will move from tidbits in media newsletters to the silver screen. “The Devil Wears Prada 2,” a follow-up to the 2006 hit that helped make Wintour a household name, has just begun filming. It follows Wintour’s stand-in, Miranda Priestly, navigating the digital revolution.

And on the podcast front, a look at what made the company so extraordinary in its prime is the subject of “The Nasty,” featuring remembrances from Condé Nast’s power players on the elevator gossip and the famed Frank Gehry-designed cafeteria at 4 Times Square.

Meanwhile, Mr. Big and Carrie — also known as former Condé publisher Ron Galotti and writer Candace Bushnell — are still trading barbs in the press, in recent pieces in New York Magazine and the Times.

Welcome back to the ’90s!

The latest cultural artifact to capture this longing for an earlier, more sparkly zeitgeist is “Empire of the Elite: Inside Condé Nast, the Media Dynasty That Reshaped America,” by New York Times media reporter Michael M. Grynbaum.

Tracing the Newhouse family business that owns Vogue, Vanity Fair and the New Yorker throughout the 20th century and into this one, the book’s buzziest reporting focuses on the careers of Brown, Carter and Wintour.

Their 1980s go-getter tenures saw them begin as outsiders who, through their unusual points of view and the largess of Si Newhouse, created a powerhouse of influence and style — “one company in Manhattan told the world what to buy, what to value, what to wear, what to eat, even what to think,” Grynbaum writes — that is the subject of continued fascination on social media and in pop culture writ large.

“When you look at Condé Nast, it’s almost the history of social aspiration. And this goes back all the way to the founding: Vogue comes out of the 400 and the Gilded Age,” said Grynbaum in a recent interview, referring to the list of society insiders established by Caroline Astor in the late 19th century.

“If you look at the Condé Nast of the mid-century, you see the WASPy, eastern establishment of the sack suits and threadbare sweaters, and it has this kind of understated aesthetic. By the time you get to the ‘80s, you have the rise of Wall Street and Gordon Gekko, and this newfound willingness to flaunt.”

As Grynbaum noted, Brown’s first issue of Vanity Fair appeared the same week that “Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous” appeared on TV.

“It represented a new establishment,” Grynbaum said, “and idea of what it meant to be successful in America at that time.”

You can see why younger generations are fixated. Grynbaum’s book has all the goods to induce mania in anyone with aspirations to work in media, mostly a rare combination of shocking budgets and provocative taste: anecdotes about expense accounts, interest-free mortgages on West Village townhouses and photoshoots with eye-popping budgets for items like $US30,000 ($AU46,000) to rent a live elephant.

Carter would dispatch his assistant to travel destinations a day in advance to set up an exact reproduction of his New York desk, complete with pencils (and no paper clips — he had a distaste for them that was noted in the staff manual).

One editor was told that her chosen hotel wasn’t splashy enough — upgrade!

“It was considered unprofessional to go into the office in flat shoes. Maybe a pair of Chanel ballet flats, but a pair of brogues, absolutely not,” Vogue writer Plum Sykes tells Grynbaum.

Writers and editors FedExed their luggage so they didn’t have to deal with it on the plane. (In business class, or the Concorde, of course.)

The accounts of this time of pure luxury are rollicking even as you become desensitized to them.

Picture this: Carter had just landed in Venice in 2006 for a Condé retreat with the business’s top editors and executives, when he realised he’d misplaced his top-secret mock-up issue of Portfolio, the company’s not-yet-launched business magazine that had been given to him confidentially.

He called his assistant Jon Kelly (now a founder of digital media start-up of Puck), who had just landed on a red-eye from New York, and told him that he’d probably left it on a gondola.

Kelly, armed with his usual 10,000 euros in petty cash for such trips, spent the next several hours bribing gondoliers until he turned up the issue.

It’s an equally impressive tale of unimaginable resources and assumptions of powerful editors, plus the bygone maniacal pluck of their lowly assistants.

It recalls a scene from “The Devil Wears Prada” in which Anne Hathaway, as Miranda’s struggling assistant, Andy, manages to find a copy of the not-yet-released Harry Potter book for the editor’s daughters.

And it would make a much more glamorous (and likely entertaining) film than the “Prada” sequel. Who wants to watch Miranda Priestly square off with traffic reports?

But the most provocative, eyebrow-raising reveal from the book is this: We still live in the world Condé Nast and its intimidating editors created. We just don’t know how to make sense of it, because we lack the requisite curatorial eyes.

TikTok is filled with home tours that recall the real estate porn of Architectural Digest; even though they’re probably out of reach, we’re still obsessed with decoding the behaviours and wardrobes of the ultra-elite.

“Our contemporary Instagram culture — airbrushed, brand-name-laden, and full of FOMO, where pretty people do pretty things in pretty places without you — is a DIY replication of the universe that the celebrity editors of Condé Nast carefully created month after month, year after year,” Grynbaum writes.

He argues that, although it may be Brown’s tenure at Vanity Fair that is most often celebrated, her time at the New Yorker was more audacious and revolutionary: “It is striking to realise the degree to which her tenure, so controversial in its day, laid the template for our modern notion of upper-middlebrow journalism,” he writes.

“Tina’s approach was giving elite Americans permission to think seriously about subjects that the old version of the magazine had rarely deemed worth of deep consideration: tabloid scandals, hit sitcoms, right-wing demagogues, porn stars.”

Today, Grynbaum said, “I think we get bombarded by different sources of information all day long on our phones. And as much as it’s been great to see the rise of new voices in the culture that may have not had a forum in the past, now we live in a state of chaos. I think we’re yearning for curators, social curators.”

What magazines like Vanity Fair, Vogue and GQ did in their prime was help readers make sense of the world — which, now, with social media and the reliance on video content, is even messier.

It’s not for nothing that the role of the editor in chief, not the designer or photographer or critic, is the one that most young women aspire to have in fashion.

For decades — maybe even centuries, if you want to look at the fashion magazines that emerged in the 18th century to track the whims and shopping sprees of Marie Antoinette — the power of choice, of pointing to one skirt, or restaurant, or reporter, play or artist over another, has been a potent domain.

Condé’s elitist reputation is one it has long struggled to shake — those stories make for some of the funnier and more disturbing reporting in the book, such as a writer’s recollection of losing out on a job for eating asparagus the wrong way — and was first the source of its power, then a contributor to its fall. Wintour in particular has tried to broaden the outlook and perspective of Vogue, with uneven results.

Yet the new media that has emerged largely replicates the Condé way. Grynbaum pointed out that many of the most popular Substacks — such as the various shopping newsletters and Emily Sundberg’s Feed Me, a highly influential roundup of gossip and stories from across tech, media, style and business — are about an unusual person’s singular perspective. There is still a desire for figures who can point us, and our attention spans, to what is worth watching, buying, talking about or pondering.

Ultimately, what do we long for when we long for the golden age of Condé Nast? It is the dream of having money — and taste.

Originally published as Magazine editors used to be gatekeepers. Do we need them anymore?