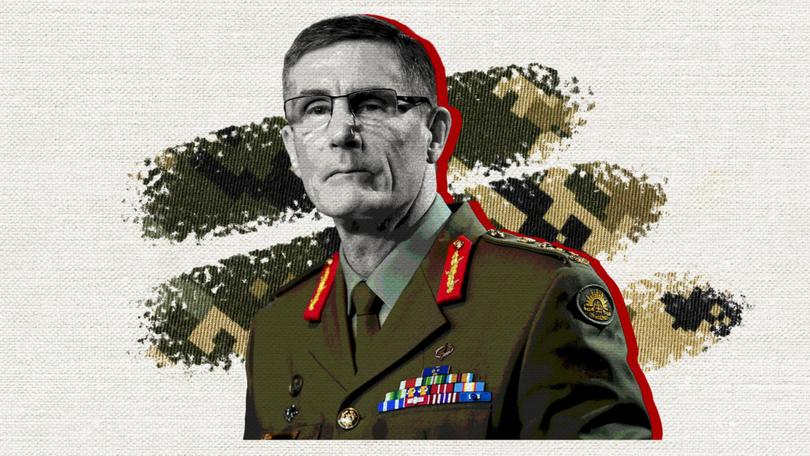

CHRISTOPHER DORE: Defence Force chief Angus Campbell has a chest full of medals . . . he should hand them back

In an epic display of gormless, grinding, suffocating prevarication masquerading as leadership, the nation’s top military officer presented as the final witness in the royal commission into veteran suicide.

General Angus Campbell has a chest full of medals.

Undoubtedly, each of them well deserved. A lifetime of service. A commando, a commander, a political aide, our top soldier. Campbell will end his military career at the top of the chain of command, the Chief of Defence Force.

For a graduate of Duntroon, it doesn’t get any better than that.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Distinguished Service Cross. Afghanistan Medal. Commander of the Legion of Merit. An Order of Australia. Even a United Nations Medal. There are more accolades, many more, including from our allies.

He should hand each of them back.

Angus Campbell has been the chief of the Defence Force for six years. Before that he worked as chief-of-staff to two previous Defence chiefs. He has been the head of the army. Decades in leadership positions.

He is due to retire in a few months.

He should go now.

Campbell loves words. Loves jargon. Not technical military vernacular, not battlefield strategy and tactics. There’s no frontline patois and knockabout Aussie slang.

Campbell’s expertise is management school garbage. Gibberish. Gobbledygook. Circular bureaucratic nonsense.

In an epic display of gormless, grinding, suffocating prevarication masquerading as leadership, Campbell, the nation’s top military officer, presented as the final witness in the harrowing, awful Royal Commission into Defence and Veteran Suicide. For half of his reign as Defence Chief, this inquiry has heard the most disturbing evidence imaginable about how and why some of the 1600 military men and women had taken their own lives over the past two decades.

Gut-wrenching, tear-jerking tales of ruin. Families heartbroken. Lives lost. And a complete absence of military leadership.

Defence initially claimed suicide rates were higher in the general community. Royal Commissioner Nick Kaldas now says it’s 30 times worse among serving and ex-military, and the actual death toll is likely more than 3000. Astonishingly, 20 times more Defence members have died from suicide than have on active duty.

Campbell and his brass at Defence HQ in Russell have had ample time, in the three years since this inquiry was forced upon them, to do something about this national crisis. Something. Anything.

Instead, Campbell told the royal commission, literally in front of families still mourning the loss of their loved ones in uniform, that Defence was on a “journey”. And we haven’t been able to “shift the dial” just yet. It’s a process. It’s hard.

Rather than come armed with solutions. Actions. He came with an apology. A classic crisis management 101 apology.

As welcome as it surely was to some devastated families, in truth it was rendered hollow and meaningless alongside the hours of Campbell’s incomprehensible psycho-babble that followed.

The words of the apology sit here as hopeless and forlorn on a screen now as Campbell’s delivery was sitting in a hotel meeting room in Sydney last Thursday.

“Our people deserve and should rightly expect the wellbeing support and care they need both during and after their service.

“I acknowledge that this has not always been the case and has tragically led to the death, by suicide, of some of our people.

“I apologise unreservedly for these deficiencies.

“Defence is committed and I am committed to doing better.”

The barrister assisting the inquiry, Erin Longbottom, KC, made a point later that apologies during this royal commission have had a way of appearing at opportune times for some witnesses.

In the hours following that apology, Campbell was astonishing.

Campbell, who has a masters of philosophy from Cambridge, is the commander of a 100,000-strong armed force. The General. He’s not The Thinker. He’s the nation’s military leader.

If any of his men and women were watching they could have been forgiven for thinking they went to bed as soldiers and woke up as management consultants. This was an excruciating extended episode of Utopia, without the satire, or frankly, the sincerity.

Campbell would have been handy at Gallipoli. Give him a megaphone, let him talk and the Turks would have either fallen asleep, surrendered or stood up demanding to be shot.

Anything to make it stop.

Remember this is the same Angus Campbell, the same Chief of Defence Force, who wanted to punish all 3000 Special Operations Task Group personnel who served in Afghanistan between 2007 and 2013, stripping each and every one of them of their meritorious unit citation over unproven, untested allegations of war crimes against some of them. No top brass included.

This is the same Angus Campbell, a former SAS operator, who in 2011 as a major general was joint forces commander responsible for all Australians deployed in the Middle East, including Afghanistan. He was awarded a Distinguished Service Cross and promoted to deputy chief of the army for his efforts. No looking back.

In his own words appearing before the royal commission, Campbell, in a rare moment of clarity and insight, made the case against his own leadership: “It is the responsibility of leaders, at all levels, I am the chief of Defence Force, I am accountable for everything that happens in the Defence Force and everything that does not happen in the Defence Force.”

When tested on this magnanimous stance, well.

Our Chief of Defence Force, who once parachuted out of planes into battlegrounds, has surrendered to corporate claptrap.

To understand just how tedious Campbell’s circumlocutory is, he has to be read in chunks. Bear with it. It is truly mind-boggling, literally and figuratively.

Asked, how it is that Defence can execute complex military operations with precision, yet can’t come up with an effective strategy to tackle outrageous rates of suicide, Campbell actually said this: “Part of it is that story of disaggregated federation moving to aggregated integration. Part of it is the underlying story of data visibility and connectability. Part of it is the compartmented nature of elements of our data and our approach to care. Part of it speaks to requirement to things like the Privacy Act and none of that I accept as satisfactory and all of that is what we are working to move past.”

Campbell refuses to accept that as chief he has not done enough, quickly enough, to address the string of service-related factors, such as “unacceptable behaviours” of others, that contribute to mental health episodes and suicide. It’s hard you see, you know because we are army, navy and air force. Not connected. Siloed. It took 22 months to build a “single expression of the values and behaviours” expected across all of Defence. “The importance of that is that it then creates a very clearly articulated common foundation for expressions of what is the cultural behaviours, the norms, the organisational expectations, across the entire enterprise.”

And then later, he said this: “In the mental health and wellbeing branch sense it needs to be an aggregated policy approach connected to an aggregated data approach connected to an aggregated personnel system approach connected to an aggregated doctrine approach connected to an aggregated values and behaviours approach. It all has to work together and that’s what we have been building.”

Those “values and behaviours” expected of service men and women are now detailed all over the place. For all to read and understand. “It is everywhere, all through our doctrine, multiple publications, it’s in signage, it’s in lesson plans, it is an expected requirement that people know what our values are . . . and that in their own way can describe what it means and what it means to them.” Can we see? I can get you a copy.

What is it? “Our values?” “Service, courage, respect, integrity and excellence — they are then described individually as aspects of character.

“And then there is a short set of expressions of behaviour we would expect to see as demonstrations of you living those values.”

Campbell says the key is to be “laser-like focused on the right values, the right behaviour and culture”.

“My point is … “, “we have learnt from pathway to change one and pathway to change two”, “we are taking reflections”, “to take a next step”, “but this is a journey”, “that document is only as useful as its lived expression”, so “application of the strategy of the leader tool kit”, and the “defence culture blueprint”, “to review our progress”.

This. Is. Seriously. The. Chief. Of. Our. Armed. Forces.

How is Defence dealing with stigma, stopping service men and women from raising issues of mental health for fear they will be ostracised and even forced out of the military?

Well I’m glad you asked. It’s “a constant conversation”, “are you OK”, “encouragement at a whole lot of levels but particularly at local tactical team level”, “it is an effort built on conversation”, “in the workplace”, “and those wider frameworks”, “it is very difficult”.

Imagine, our top military leader wargaming, not with other generals, but with HR consultants from people and culture.

When it comes to sexual assault. Well that’s tricky, too. The data is not good. But we are trying. “People are conscious that reporting through a number of pathways can lead to pathways of preferred action.”

“There is a mechanism of feedback that the action has occurred, that there has been a realised effect and inevitably knowledge of that bolsters and strengthens confidence that through a preferred reporting change something can be done and that others know something can be done.”

And he goes on and on and on.

Words. Words. Words.

These are responses to questions about preventable suicides, about sexual assault, about mental illness, about financial, family and battle-related stresses and crises. This is serious stuff. About human beings. Over more than 20 years of institutional failure. Of Defence Force leadership failure in fact. For which he admits, and has already apologised. Now being asked to detail his considered responses, some ideas and solutions, three years after this inquiry began and nearing the end of your term in charge … I’d prefer to leave it to the royal commission, he says.

And Campbell litters his answers, in fact, restricts his answers, to utterly unconvincing, devastatingly so actually, impossible to understand blah. Calm, considered, robotic rubbish, devoid of concrete actions.

It is a total capitulation to heartless, effortless, action-less management-speak and cumbersome organisational theory. Systems and processes, PowerPoints, structures and flows, and charts and arrows to circles and smaller arrows to even smaller circles.

Our Chief of Defence Force, who once parachuted out of planes into battlegrounds, has surrendered to corporate claptrap.

It might be sensational in theory, Max Weber this and Henri Fayol that. But in reality, it is a vacuum where leadership should reside.

Imagine, our top military leader wargaming, not with other generals, but with HR consultants from people and culture.

It’s the enemy within and his accomplice from McKinsey.

If this wasn’t so horrendous, you would laugh, a hilarious Stanley Kubrick take on the evolution of modern military leadership, from Carl von Clausewitz to General Stanley McChrystal to Peter Drucker. Warped and wayward. This is language and leadership so far removed from the soldier, sailor and aviator as to be rendered rotten and unreliable.

The royal commission, led by Nick Kaldas, the former NSW police officer, has done remarkable work airing the tragedies Defence leadership was so intent on playing down. And with its ineptitude exposed, we can see why.

Fed up with Campbell’s long-winded, laborious and loquacious lessons in ineffective change management, Erin Longbottom, KC, the feisty, erudite Queenslander, cut through the tedious torture: “Large organisations take time to change but you would accept that for the members and the veterans and their loved ones who have lost members while Defence has been on that ‘journey’, that really is a tragedy?”

Campbell: “Yes, it is absolutely a tragedy.”

Give it away, cobber.