EDITORIAL: Social media giants must do more to stop sextortion

EDITORIAL: It’s good news that someone is being made to answer for a NSW boy’s ‘sextortion’ death. But it’s the social media companies that must be held to account.

The death by suicide of a NSW schoolboy duped into sending intimate images to an African crime gang he came into contact with via social media has shocked Australia.

The boy was apparently so distressed by the group’s demands that he pay them $500 in online gift cards — or they would send the images to his family and friends — that he took his own life just hours later.

The circumstances are a shock to us, but it shouldn’t shock the heads of the social media giants that these con artists use to conduct their crimes.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Because tragically, this boy’s death is not an isolated incident. Reports of sextortion — a form of blackmail in which someone tricks or manipulates another into sending sexual images and then threatens to release the images — are rising. According to the Australian Centre to Counter Child Exploitation, teenage boys are most likely to be targeted.

American James Woods was in his final year of high school and weighing up his university options when he was contacted on Instagram last November by someone who appeared to be an attractive young woman.

James was persuaded to take part in a naked video chat with the profile. Screengrabs of that video chat were later used to blackmail the promising young track athlete.

At one point the scammers told James: “You may as well end it now”.

He died by suicide soon after.

Twelve-year-old Canadian boy Carson Cleland took his life in similar circumstances last year.

There are many other cases.

In NSW alone, reports of sextortion are up almost 400 per cent in 18 months, according to the State’s Cybercrime Squad commander, Detective Matthew Craft.

“But the good news is people are reporting it and there are steps we can take to help you before it goes too far.

“We want young people to continue to report these cases and to never be embarrassed to talk to police.”

South Carolina Republican politician Brandon Guffey, whose son Gavin died by suicide in 2022 after becoming a victim of sextortion, is suing Mark Zuckerberg’s Meta, the company that owns Facebook and Instagram.

He says the company’s “criminal negligence” in concealing research of its platforms’ harmful effects and doing little to keep children safe from harm, contributed to his son’s death.

Sextortion isn’t the only threat to child safety on social media. Vulnerable children are also vulnerable to sexual predators, cyberbullying, and anxiety and depression caused or exacerbated by excessive social media use.

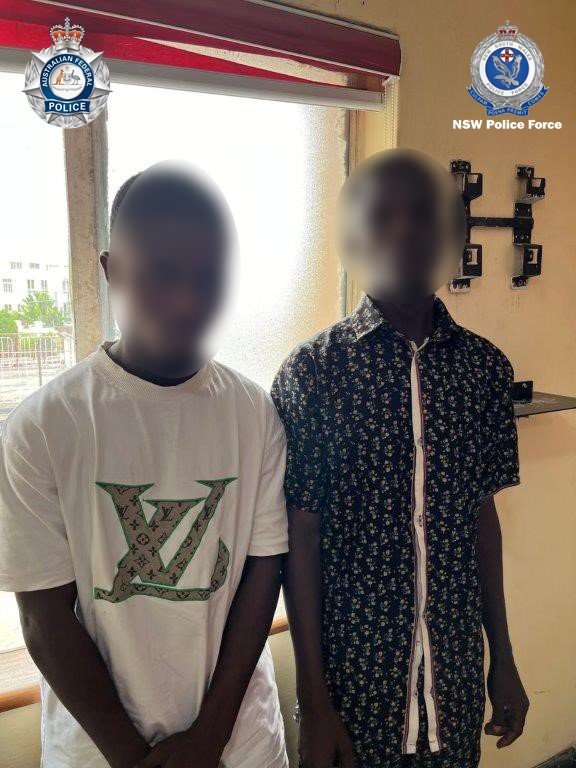

Police have charged two Nigerian men they say were responsible for hounding the NSW boy to his death. They will be dealt with by the Nigerian justice system.

It’s good news that someone is being made to answer for the boy’s death.

But even a successful prosecution will do little to slow the tide of sextortion cases.

In order for that to happen, it’s the social media companies that must be held to account.

Lifeline 13 11 14

Kids Helpline 1800 55 1800

Responsibility for the editorial comment is taken by The Nightly Editor-in-Chief Anthony De Ceglie.