EDITORIAL: Why Australians must defend the right to offend

EDITORIAL: Regardless of their feelings about Pauline Hanson’s divisive brand of politics, Australians who believe in freedom of speech and the right to political expression should back her in this fight.

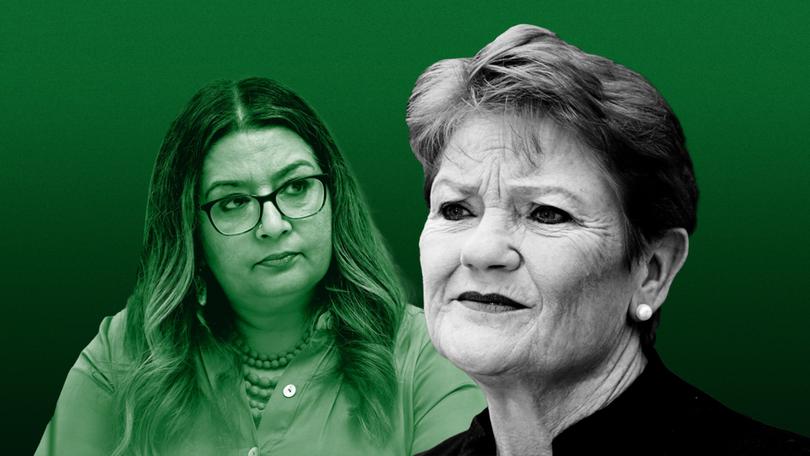

Pauline Hanson’s tweet telling Greens Senator Mehreen Faruqi to “piss off back to Pakistan” was rude, gross and offensive.

As was the tweet from Faruqi which prompted that distasteful response from Hanson.

Faruqi had posted, on the day of Queen Elizabeth II’s death: “I cannot mourn the leader of a racist empire built on stolen lives, land and wealth of colonised people.”

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Odious, deliberately provocative stuff from both sides.

But it’s only Hanson’s comment that has been found by a court to constitute unlawful discrimination.

Federal Court Justice Angus Stewart on Friday concluded Hanson’s “Islamophobic” comment racially vilified Faruqi, who is a Muslim who came to Australia from Pakistan when she was 19.

Faruqi’s weapon in her battle against Hanson was that old enemy of free speech and political expression: Section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act.

18C makes it unlawful to “offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate” a person or group on racial or ethnic grounds.

On no other basis do we outlaw rudeness? You can say any offensive or insulting thing about a person based on their gender, sexuality, appearance, political affiliation or disability.

That, in the eyes of the law, is fine.

That doesn’t mean there aren’t consequences to saying those offensive or insulting things.

You may find yourself socially ostracised. You may find it difficult to get a job. You may find people say offensive and insulting things right back at you.

But you won’t find yourself in a courtroom.

18C is so broad, so open to interpretation, and so vague as to be dangerous.

It’s also useless. Outlawing saying repugnant things on the basis of race or ethnicity doesn’t do anything to stop people from holding racist views. If anything, making it unlawful to express those views serves only to further entrench them and further alienate their holders from the mainstream.

Australia rightly has legal provisions which outlaw the incitement of hatred and violence against a person or group.

If Hanson had threatened Faruqi or urged her followers to commit acts of violence against her, she would have committed a criminal offence.

But she didn’t. She said something which the majority of Australians would find discourteous and distasteful.

We should not legislate for civil discourse. In the words of former attorney-general George Brandis, in this country, people have the right to be bigots.

Or they should.

Hanson, who has been ordered to delete the post and pay Faruqi’s legal costs, has vowed to take an appeal to the High Court for what will be a legal showdown in defence of offence.

Hopefully, the outcome of that will be to put some guardrails around this overly broad and easily exploited law.

Regardless of their feelings about Hanson’s divisive brand of politics, Australians who believe in freedom of speech and the right to political expression should back her in this fight.