JUSTIN LANGER: Special family gives unique insight into the power of forgiveness

David Warner stood by my side on the Lord’s balcony this week.

Davie is a man who brings life to every changing room. He has been through his fair share of heartache over the last few years, but his energy is undeniable — as is his humility in dealing with a section of the public who seem unable to forgive him or his teammates for their roles in the Sandpapergate saga seven years ago.

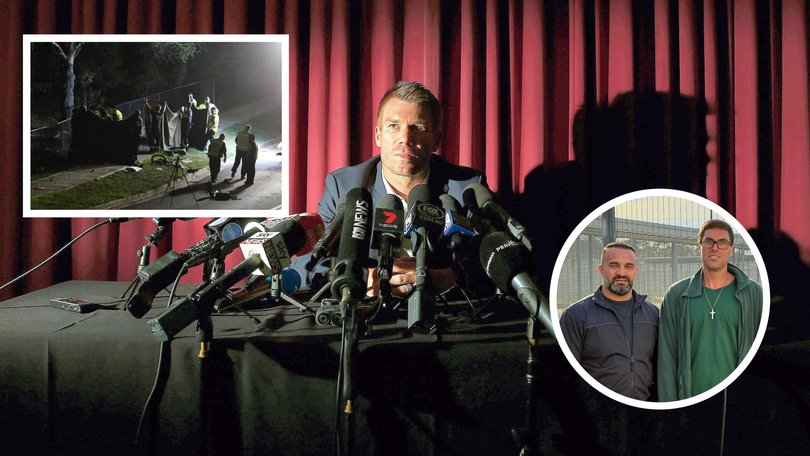

On Monday at Lord’s, he asked me quietly if I had watched 7News’ Spotlight program, Face to Face with My Children’s Killer.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Admitting I hadn’t, he told me he had been moved by Michael Usher’s mind-blowing interview, especially the unimaginable courage and wisdom of an extraordinary man named Danny Abdallah.

“On one hand harrowing and the other, a heart-warming demonstration of grace, kindness, compassion, understanding and forgiveness. Powerful!”, is how Channel 7 described the program.

Having now watched it, I would go a step further to say I was observing a living saint recounting the unimaginable pain of losing his three children and niece to a drunk driver, and the journey he and his family have taken to find peace through forgiveness.

Their story is more than powerful; it is a miraculous example to everyone.

Danny Abdallah and his family’s world shattered on a February evening in 2020.

A drunk stranger’s reckless choices stole three of his children from him. Antony, Angelina, Sienna and their cousin Veronique, became names etched not just on headstones, but on a nation’s conscience.

I remember clearly the impact of carnage and destruction reported that night.

Walking down the street, like any of our kids have done, laughing and joking with their cousins, their beautiful moment of normality was suddenly turned into “a war scene. Not something you would expect to see in Australia,” as described by the father who has lost his world.

The driver, Samuel Davidson, became the face of senseless loss.

A young man whose split-second decision to drink and drive destroyed multiple families, including his own. Davidson said he’d suffered years of depression, exasperated by the death of his sister, and was a self-confessed weekend binge drinker and occasional drug user.

On that fateful night, he sat behind the wheel of his car blind drunk. Not long after, a tragedy that rocked Australia and changed lives forever occurred.

“I am haunted, and I don’t know why I did it”, he told Usher.

A few days after the tragedy, the children’s mother, Leila Abdallah, told reporters she had forgiven Davidson.

Forgiven him?

Most Australians were shocked by her admission after she prayed at the site of each of her children’s final resting places.

Leila said: “I forgave the driver that tragically killed our children alongside with their cousin Veronique. And the reason I forgave was I wanted to be obedient to our Lord and Saviour and honour Him at whatever cost.

The family also released a public statement saying: “We forgive the driver that killed our innocent children. His actions will be met before the earthly and heavenly judge.”

The “earthly judges” handed down their 28-year sentence, a cold mathematical verdict of justice.

For the last five long years, Davidson has sat behind bars suffering for his sin; a sin made bearable by the realisation that his victims had publicly and privately forgiven him.

“Their forgiveness brought hope, without hope I would be nowhere,” he confessed.

But what shines through from the courage and humility of the Abdallah family is not so much how the perpetrator reacts to their forgiveness but rather, what the action of forgiveness does for them, the victim.

In their words: “Forgiveness is the greatest gift you can give yourself and others. The more you practice the better you become at it, and it allows you to live peacefully and to heal. Forgiveness is more for the forgiver, than the forgiven.”

In Usher’s commanding interview, my heart missed a beat when Abdallah and Davidson came face to face in the maximum-security prison that Davidson currently calls home.

Their meeting defies all imagination, reads like fiction, but cuts with the sharp edge of reality.

My mind was constantly asking how I would react. The natural emotion was that I think I would want to kill the person who killed my kids.

But as Danny Abdallah walked into that prison to face the man who killed his beautiful children, it became apparent that his objective was not one of revenge, nor closure in any conventional sense, but rather for something far more profound.

His actions were of a man who had a chance to practice the kind of radical forgiveness that transforms both victim and perpetrator

“If it was up to me, I’ll bring him out tomorrow,” Abdallah said — words that must have echoed strangely in that institutional space. “My children kneel down every night and say a prayer for Sam”, he said.

This extraordinary encounter represents restorative justice at its most powerful. Unlike traditional criminal justice, which asks “what law was broken and how should we punish?”, restorative justice asks deeper questions: “Who was harmed? How can we heal? What does real accountability look like?”

In those prison walls, facilitated by specially trained professionals, two humans grappled with questions that haunt us all.

Why do we hurt each other? How do we live with irreversible consequences? Can genuine remorse meet genuine forgiveness?

It was apparent that Davidson has faced the full weight of his actions, not just the legal consequences, but the human cost measured in a father’s tears and a family’s permanent absence.

In Danny Abdallah’s case, confronting the man whose name had become synonymous with any father’s worst nightmare, chooses to see beyond the crime to the broken human being who committed it.

Their meeting was challenging to watch. In a world that often equates justice with vengeance, here was a father saying the only justice was having his children back; impossible, of course, but honest in its simplicity.

He said profoundly: “In my case I have learned that “justice isn’t for the victim, I think it is for the community.”

This wasn’t about excusing the inexcusable or diminishing the severity of Davidson’s crime. Rather, it was about two people choosing a harder path than hatred, a path toward understanding, accountability, and perhaps, healing.

In that prison room, restorative justice revealed its true power, not to replace traditional justice, but to supplement it with something the courts cannot provide, the possibility of human redemption, one conversation at a time.

The day after Davie encouraged me to watch Spotlight, he was booed again by the crowd at The Oval in London.

This is a daily occurrence when he plays here in England. To be honest it makes me so frustrated. Annoyed. When is enough, enough?

He paid his penalty and yet is reminded every time he walks out onto a cricket ground.

Obviously, his example is nothing compared to the gravity of grief suffered by so many in the world, but forgiveness does work on a spectrum worth talking about.

Not for a second would I ever question another person’s reaction to pain and suffering, but I do believe the world could be a better place if it followed the Abdallah family who released their “Four Steps to Forgiveness” in February this year.

Through the I4Give Foundation, set up in honour of their three lost children and their niece, they offer a structured approach to processing grief.

The 4 Steps to Forgiveness:

- Acknowledge: Recognizing what has happened and the hurt that has been caused

- Accept: Coming to terms with the reality of the situation

- Surrender: Surrendering to God (reflecting their Catholic faith)

- Voice Forgiveness: Actually speaking or expressing forgiveness

Specifically created to help people who have suffered trauma by learning how to process their grief and find a path toward forgiveness, Leila Abdallah emphasises that: “Forgiveness is a decision, not a feeling. It is for your peace, not for the other person.”

Impossible as that may feel at times.