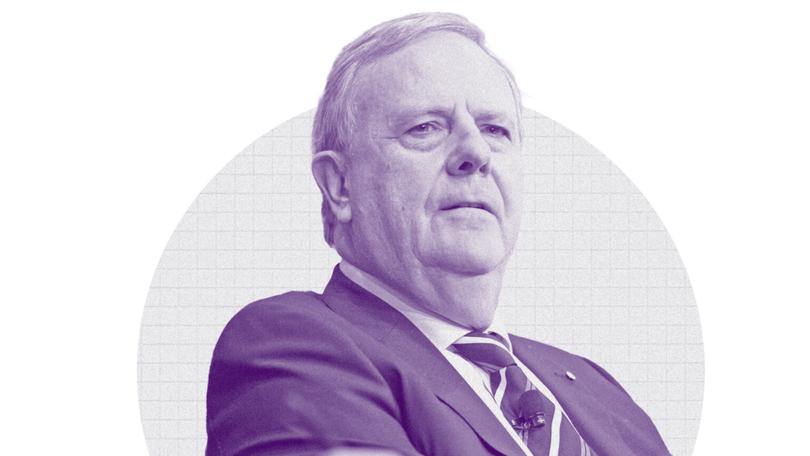

THE FRONT DORE: Peter Costello has always had a problem with journalists. This blow-up should not surprise

THE FRONT DORE: Peter Costello has always had a problem with the media, as well as a lofty opinion of his own talent. This ugly incident involving a journalist should come as no surprise.

Peter Costello has always had a problem with the media.

That’s why he was an absurd choice as chairman of a media company. He doesn’t understand journalism, and despises journalists. Always has. Every one of Nine’s proud and passionate journalists who have had anything to do with him would know that, either through experience or instinct.

To be fair, hatred and bitterness are Costello’s constant companions, not a grace he reserves for journalists. As a politician, he had a similar regard for most of his colleagues.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Costello has such a lofty opinion of his own talent, his generational brilliance, he has always struggled to abide others.

Burdened by expectation and struck numb by entitlement, Costello became bitter and unhappy in politics. He will never be remembered as anything other than a competent treasurer, if he’s lucky, a passage or two in any general account of Australian history.

Unlike the Labor towers before him, generally clumped together as the Hawke-Keating years, the successful Coalition decade that began in victory in 1996 will only ever be thought of and reflected upon as the Howard era.

Costello was a Liberal powerhouse in the years leading into government, and was obviously a significant figure in the Coalition’s success. But he was dominated by Howard, who consistently stepped all over his prized budgets and thwarted his succession ambition by declining Costello’s ever so polite request to kindly step aside.

Costello treated the national accounts, and the revenue from Australian taxpayers, as if it were his own. Howard treated Costello as a bank teller.

Unlike Paul Keating before him, Costello never turned the charm on for the Canberra press gallery, never brought them into the tent and along for the ride. Keating was on a mission to change Australia, to make a mark. Ambitious for himself, obviously, but also for the country. Keating, the original influencer, sought to sweet-talk people around him, including journalists who he thought he could rely on to help him express his vision. Those who didn’t get it, he brutalised. It worked until it didn’t. Costello didn’t bring the charm. He brutalised and belittled.

Rather than whinge to anyone who had the misfortune to listen — and by that read: everyone in Canberra — if Costello had the personality to win over Australians, including influential journalists, and the gumption to seize power from a weakened prime minister in the dying days of Chez Howard, the course of history may have been different.

If Costello, wrecked by hapless defeat, hadn’t sulked off out of politics in 2007, he may well have reclaimed power for the Coalition when Kevin Rudd’s time in the Lodge imploded prematurely. Who knows. Unsurprising then that looking back, as he would in his reflective moments, sitting alone in his dark Melbourne library, Costello, Boy Wonder, would be haunted by history.

I shoulda been a contender.

Costello is a big, boofy bloke these days. Heavy-set, as The Nightly described him. He has always liked to throw his weight around, metaphorically at least. Although, those in the press gallery in the late 1990s also recalled yesterday that during the one annual “politicians versus journos” Australian football game he played, the then-treasurer was happy to run through a few journalist opponents who stepped into his path to the goal square.

In politics, Costello was always the type of politician to complain about stories. Not to the journalist, or the editor, but to the CEO. It’s a fool’s tactic. CEOs of successful media companies don’t instruct editors or journalists on how to do their job. An experienced CEO in receipt of an angry call from a politician such as Costello, or Kevin Rudd, would more often than not listen intently to the complaint and share their frustration and disappointment: “I am as disappointed as you are, Treasurer”. Assuming no mistake had been published, and the complaint was spurious, the next call would be to the editor, passing on the message from the politician under the unspoken expectation the editor would more than likely be outraged and insulted by the politician’s shoddy attempt to muzzle the newspaper, and the editor would subsequently encourage their reporter to go harder.

Costello never understood how to manage journalists, who at their best offer no favours to any politicians, regardless of their persuasion.

So for Costello to find himself at the helm of Nine, one of the nation’s largest employers of journalists, including his own son Seb Costello, is beyond odd.

His old mate James Packer, who inherited ownership of Nine from his father Kerry, has described the Costello-era eight years as chairman as a disaster. It “hasn’t been good” for investors, he said.

“I think being the chairman of Nine is all he has left and he will try and keep the job for as long as he can,” Packer told The Australian. “His time as chair hasn’t been good for shareholders.”

Costello has been under enormous pressure in the wake of the scandal engulfing Nine following accusations of bullying and harassment against its long term top news man Darren Wick.

Staff, mostly women, have revolted against their own company, privately briefing journalists at rival media companies about the drama in the newsroom.

Costello has not fronted up. A single written statement defending his CEO Mike Sneesby. He has himself faced questions about his own relationship with Wick, and Wick’s relationship with Costello’s son, a TV reporter who has often found himself in the headlines for behavioural issues over the past decade.

Costello is naturally very protective of his son.

Faced with questions from journalists over the past few weeks, Costello has had no hesitation employing his old, failed, tactic of escalating complaints above the head of the journalist asking the tough questions. Rather than answer the questions, or even deal directly with serious journalists, Costello has gone directly to their bosses.

Costello is never shy about throwing his weight around on the telephone. So it really should come as no shock to anyone that when confronted by a pesky journalist doing his job, that Costello would take it a step further and throw his shoulder into his inquisitor.

Having a journalist in your face is never a pleasant experience.

News Corp’s executive chairman Michael Miller this week put himself out there, addressing the National Press Club and fronting up to a testy interview on ABC Radio National. He did so to take a principled stand on the outrageous behaviour of the tech giants. He faced intense questioning from rival media outlets, including Nine, intent on maybe trying to embarrass him, or in the hope of prompting a misstep. It would have been an uncomfortable experience. He was doing it for the greater good of journalism.

Miller met the provocative, at times misleading and mischievous, questions professionally and politely.

Costello, faced with legitimate, unanswered, questions about governance of an ASX-listed business, smirked and sunk the shoulder in.