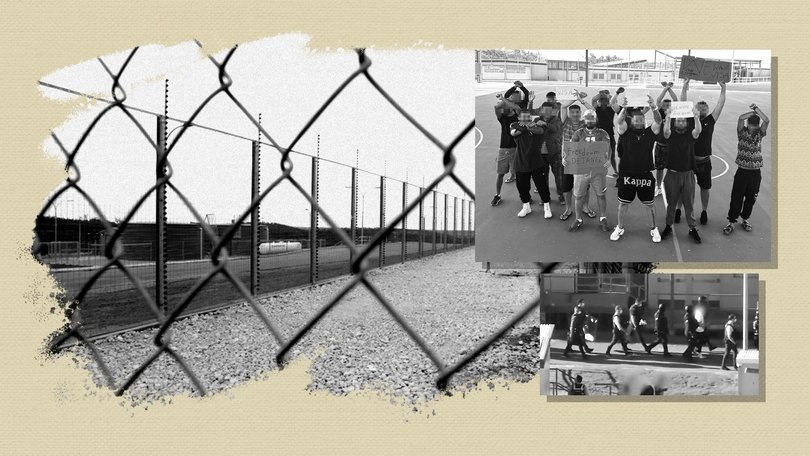

Detainees would rather be in jail than immigration centres: Ombudsman

Threats to jail people who do not comply with efforts to deport them may not work because many immigration detainees would rather be in jail, the Government’s Ombudsman has warned.

Threats to jail people who do not comply with efforts to deport them may not work because many immigration detainees would rather be in jail where there are better facilities, the Government’s own watchdog has warned.

Commonwealth Ombudsman Iain Anderson has told a Senate committee examining tough new deportation laws that immigration detention facilities are “unsuitable for long-term use”.

The new laws, which the Government failed to rush through Parliament before Easter, would impose mandatory jail sentences of between one and five years on people who refused to cooperate with their deportation.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Cooperation could include applying for a passport or speaking with officials from their home country.

Mr Anderson said the threat of jail might not be the deterrent the Government thinks.

His office continues to hear from people in immigration detention who cannot access medical care, dental treatment or drug and alcohol rehabilitation programs.’

They have also complained they cannot continue the kind of work training or life skills, such as anger management education, that were available to them in jail or while they were in the community.

“Indeed, my office has recorded instances of detainees expressing a preference for incarceration over immigration detention due to the certainty and better range of meaningful activities that can be attached with a prison term,” he wrote in a submission to the committee.

“It is, therefore, possible that the deterrence potential of a prison term has been over-estimated and that some people on a removal pathway will choose noncompliance with a ministerial direction over removal and remain in a cycle of detention and imprisonment for prolonged periods or even indefinitely.”

His latest annual report on Commonwealth detention facilities, released in January and covering the 2021-22 financial year, noted there had been a successful trial at the Yongah Hill centre outside of Perth to offer meaningful activities and programs in the evenings and weekends.

But even then there were problems, such as that detainees could only do a cooking program if they had completed a food handling qualification but that training was not offered to people in detention.

Mr Anderson also found people entered immigration detention “clean” but resumed or started taking illicit drugs while detained and then had only patchy or inconsistent access to rehab programs.

The Australian Human Rights Commission raised serious concerns about conditions at Yongah Hill in a report released on Monday, based on a two-day inspection of the centre in May 2023.

Commissioner Lorraine Finlay found there was a concerning lack of access to healthcare, including emergency, out-of-hours and mental health care.

Parts of the centre were no longer fit for purpose, there were not enough staff, and there was an urgent need for more counselling, harm minimisation and rehab services.

“The same key concerns have been raised repeatedly for many years,” Ms Finlay said.

The Home Affairs Department said it was already offering drug and alcohol counselling and rehabilitation services at the centre during business hours.

However, it said it would not be offering detainees any study or vocational training options because “unlawful non-citizens are not entitled to the privileges granted by any visa, including study rights”.

The Government’s proposed deportation laws also give the immigration minister powers to ban visas from “designated countries” that refuse to take back people who don’t want to be returned from Australia.

This has led to concerns from community groups about the implications for family members who might be seeking to join relatives living in Australia.

The committee inquiry will report by May 7.

Originally published on The Nightly