The inside story of how Labor destroyed its deep ties with Australia’s Jewish community in just 18 months

Just two years ago the PM was the honoured guest at a celebration of a man recognised as the godfather of Jewish political influence in Australia. How did things go so wrong?

The zenith of the long and deep relationship between the Australian Labor Party and the Jewish community was reached on a clear August evening two years ago in the ballroom of the Melbourne Grand Hyatt.

As Anthony Albanese arrived in black suit and a tie of deep blue for the 70th anniversary celebration of Arnold Bloch Leibler, he was embraced by one of the men the Jewish law firm is named after, senior partner Mark Leibler.

Albanese, an inner-Sydney left-wing activist who had grown up opposing Israel, was about to recognise the man many considered the godfather of Jewish political influence in Australia.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Mr Leibler had curated the Prime Minister’s shot at historical greatness, the Indigenous Voice to Parliament, to the edge of existence. Mr Albanese had come to Melbourne, two months before the vote, to recognise and celebrate his support.

“Mark, I want to say that you’ve been involved in constitutional recognition for more than a decade,” Mr Albanese told the 900 members of Australia’s elite who were dining to celebrate the firm’s partnership.

“Your role has been one of insight and influence. You are indeed an inspiration to us all. So happy birthday and here’s to the next 70 years.”

The event was more than a celebration of a firm that had come to symbolise the influence, prestige and financial success of Australia’s Jewish community. It was a moment of unity between the Jews, who had taken generations to be accepted as part of the city’s elite, and a party that could never quite decided whether it was for or against Israel.

A year-and-a-half later the relationship would be shattered. A community that had come to feel almost, but not quite, as comfortable as Australia’s Anglo elite would find itself in the position it had been trying to escape since World War II: afraid to be openly Jewish on the streets of a Western democracy.

News during prayer

Among those who experienced the tear in the most personal way was Mark Leibler’s youngest son, Jeremy, who in 2018 succeeded his father as president of the Zionist Federation of Australian, one of the two umbrella Jewish groups.

A partner at Arnold Bloch Leibler specialising in mergers and acquisitions, Jeremy Leibler had spent those years cultivating relations with the Labor Party leadership, including Mr Albanese and Defence Minister Richard Marles. Mr Leibler came to know Foreign Minister Penny Wong so well he thought of her as a friend.

On the afternoon of October 7, six weeks after his firm’s dinner, Jeremy Leibler was standing in his Melbourne synagogue holding a prayer book for the celebration of Simchat Torah, an important Jewish holiday.

Someone mentioned there had been an attack on Israel. Twenty had died, they said. Others had been kidnapped.

“We had no sense of the scale,” Mr Leibler told The Nightly from Israel, where he visited the site of the Nova dance-party massacre. “That would take weeks to understand.”

Like many Australian Jews, Mr Leibler desperately called and texted friends and family in Israel to check they were unharmed. As he and other Jewish leaders began to appreciate the ferocity of the attack — about 1200 people were killed and 250 taken hostage — they concluded Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu would go to war with Hamas, potentially devastating the Gaza Strip, which was home to 2.3 million Palestinians.

So too did the Australian government, which had access to US and British intelligence analyses on Netanyahu’s likely next step. At 7.46pm that evening, Wong “unequivocally” condemned the attack and called for the rocket attacks on Israel to end. She also warned the Israeli leader against unrestrained war, or at least that was how the Jewish leaders interpreted her statement that: “Australia urges the exercise of restraint and protection of civilian lives.”

Many Australian Jews were too traumatised by the death, rapes and kidnapping of Israelis to parse the Foreign Minister’s comments. Heartened Ms Wong had acknowledged Israel’s right under international law to wage a defensive war against Hamas, they assumed they could rely on the government to support Israel diplomatically following the greatest one-day loss of Jewish life since the Holocaust.

Ms Wong on the conduct of war

On October 27, after three weeks of bombing, the Israeli army invaded Gaza. Around the world, especially on university campuses, anti-Israel protests erupted. Asked by ABC radio Sabra Lane host if the attack was “proportionate to what Hamas extremists did on October the 7th”, Ms Wong used a phrase she would repeat over and over again: “How Israel conducts this war matters.”

Jewish leaders could hardly disagree. The statement was self evidently true. But it implied Israel was not trying hard enough to prevent civilian deaths, which was difficult when Hamas fighters did not wear uniforms, lived and fought in civilian areas, and were an arm of Gaza’s government.

On December 12, two months after the war began, the Zionist Federation of Australia and the Executive Council of Australian Jewry received a call from Ms Wong’s office. The next morning in New York, they were told, Australia’s ambassador to the United Nations would vote for an immediate ceasefire, breaking with the US and Israel.

Jeremy Leibler and other Jewish leaders were shaken by the decision. Even though Australia had supported a failed attempt to change the UN resolution to mention the October 7 attack, they concluded the government’s position was contradictory.

Speaking after the vote in Adelaide, her home town, Ms Wong said Hamas “has no place in the future governance of Gaza.”

Hamas was losing the war. A ceasefire would save its fighters’ lives. If Ms Wong wanted Hamas removed from Gaza, as she said, surely the war had to continue until Hamas was militarily crippled?

Having it both ways

Despite frustration with the Government, Mr Leibler urged measured criticism. Over 22 years in elected politics, Ms Wong had developed a reputation for toughness. At the same time she had built trusting relationships with a few Jewish leaders. If they or were too aggressive in their criticism, they risked being cut off.

Without access to the foreign minister, it would be more difficult to influence her. They could see the pressure Ms Wong was under from the Muslim community, which outnumbered Jews eight-to-one. Many Muslims lived in Western Sydney and Melbourne electorates where the Labor Party had large majorities.

Facing a potent force within their own ranks, Jewish leaders could see the huge pressure on Mr Albanese and Ms Wong to side with the Palestinians. Many of their MPs’ offices had been vandalised for the Government’s perceived support of Israel. Mr Albanese had told rabbis he could not visit mosques without being heckled.

Mr Leibler and Daniel Aghion, a Melbourne barrister who led the Executive Council of Australian Jewry, agreed to issue a statement that did not name the Prime Minister or Foreign Minister, but questioned their consistency.

“The Australian Government cannot have it both ways,” they said. “Either it stands by its position in the joint statement that recognises that Hamas must be removed from power and return all the hostages or it supports a ceasefire which would allow Hamas to remain in power and deliver on its promise to repeat the attacks of 7 October at the earliest possible opportunity.”

The Government did not agree. Ms Wong would never stop advocating for a ceasefire, or the removal of Hamas, which Australia had designated a terrorist organisation in 2001.

Going to Tel Aviv

Among members of Australia’s 100,000-strong Jewish community, their fear began to grow - a fear few Jews had experienced in Australia. They felt Mr Albanese and Ms Wong were pandering to anti-Jewish elements within the Muslim community.

Without strong legal and rhetoric support from the government, they feared an increase in the anti-Semitic incidents that began immediately after October 7, when a crowd of Muslim men appeared to celebrate on the steps of the Sydney Opera House.

Stories of other ugly incidents spread. With anti-Israel protests held in Melbourne and Sydney every Sunday, many Jews avoided the cities on weekends. A 44-year-old Jewish man was confronted in a park near Sydney Airport by three men who asked if he supported Israel. They knocked him down, punched and kicked him while shouting “Jew dog”. Suffering concussion and four fractures to his spine, he was hospitalised four days.

Relations with the Government did not improve when Ms Wong went to Israel. Unlike some other Western leaders, Mr Albanese chose not to demonstrate his support by visiting the Jewish state. Instead, Ms Wong arrived in Tel Aviv on January 16 and met the foreign minister, Israel Katz, and a few family members of Hamas-held hostages.

Despite offers from the Israeli government, Ms Wong chose not to visit villages in southern Israel where families had been murdered. Instead, she went to the West Bank to see Palestinian officials, who have not held a presidential election since 2005.

Many of Australia’s prominent Jews had already gone to the massacre sites. They included former treasurer Josh Frydenberg, who last month described the emotional power of seeing the “burnt-out homes, the ashen faces of the residents and hearing the stories of loss”. “What we saw that day will never leave me. I only wish our Foreign Minister had done the same,” he said.

Ms Wong appeared, to Jewish leaders, more focused on the Palestinians. The Foreign Minister’s staff made it sound like she had berated her counterpart for the deaths, according to a Hamas count, of 24,000 Gazans. Ms Wong had expressed “strong concerns about the civilian death toll and the dire humanitarian situation” to Katz, they said.

Attacks on Australian streets

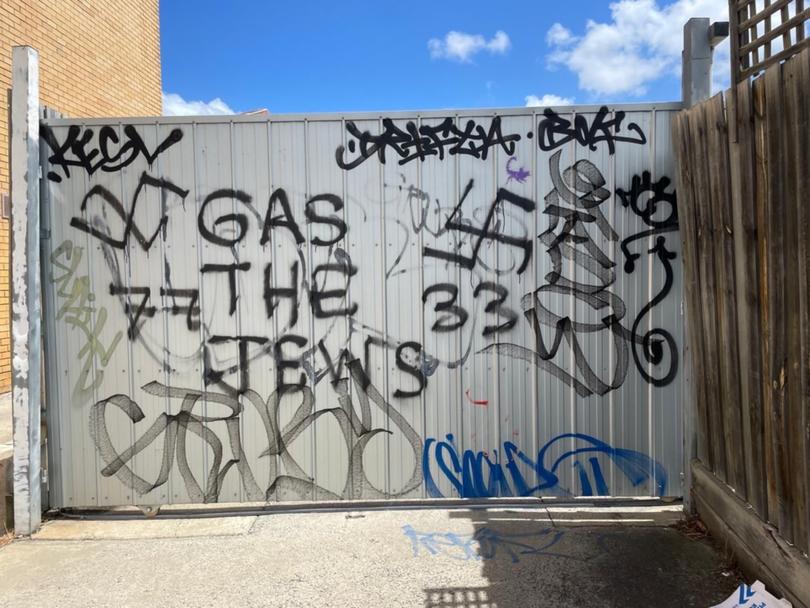

The conflict was not abstract to Australian Jews. Many had relatives in Israel, where military service was compulsory. At home, many were experiencing anti-Semitism for the first time. Australian Jews were assaulted, abused, intimidated or had their property damaged an average of four-and-a-half times a day from last January to September, according to a tally by the Executive Council of Australian Jewry.

Some cases made the news. Most did not. Synagogues asked their guards to carry pistols. Looking Jewish risked a stranger yelling “Free Palestine!” or “Heil Hitler”.

The Coalition had sided with Israel, winning Liberal leader Peter Dutton kudos from many Jews, especially when the government supported, in May, upgrading recognition of the Palestinian Authority at the United Nations. Party strategists wondered if Mr Dutton’s support would cost the Liberals votes in working-class seats it hoped to win from Labor.

Mr Albanese, aware he was being blamed for the anti-Semitism suddenly staining Australian streets, decided the moment had come to repay Arnold Block Leibler’s hospitality a year earlier. On a cold Tuesday evening in June, the Prime Minister and his chief of staff, Tim Gatrell, welcomed Jeremy Leibler and his father, Mark, to dinner at The Lodge, Mr Albanese’s Canberra residence.

The Leiblers declined to disclose what was said. But they and other Jewish leaders were concerned by Ms Wong’s advocacy for a Palestinian state so soon after the October 7 attack. Unless Hamas was eliminated and a peace deal signed, they feared an independent nation of Palestine would fight for Israel’s destruction. They wanted the Government to explicitly link its support for Palestine to protections for Israel.

Neither Mr Albanese or any other minister gave that speech.

“Had the government done that it would have provided comfort to the community that the government’s positions were grounded in principle rather than politics,” Mr Leibler told The Nightly. “[It] would have provided some reassurance that Australia’s historical, bipartisan support for Israel and the Jewish community remained.”

An aid worker killed

In August, relations got even worse. A special adviser to the government, former defence force chief Mark Binskin, wrote a broadly sympathetic report, towards Israel, about the killing of Australian Lalzawmi Frankcom and six others by Israeli forces.

An aid worker distributing food in Gaza, Ms Frankcom’s convoy was attacked by Israeli drones in April after one of its security guards fired his weapon into the air from atop a trailer. Israeli soldiers concluded the convoy was being hijacked by Hamas.

Mr Binskin, who was given access to Israeli reports and military personnel, said the aid workers were not deliberately targeted. But Ms Wong refused to concede the deaths were a terrible accident and sought criminal charges. “Zomi Frankcom and her colleagues were killed in an intentional strike by the IDF,” she said.

Ms Frankcom’s unnecessary death was a pivotal moment in Australian perceptions of Israel’s conduct of the war. When the truth emerged, Australian Jews felt sold out.

“I think it was at that point when it became clear to the community there was no principle that was driving foreign policy or how anti-Semitism was addressed is when they really fundamentally lost the Jewish community,” one Jewish leader said.

Mr Albanese felt their anger on October 6, a Sunday, when he attended a service in Melbourne to commemorate the October 7 killings. As he joined a procession of people carrying Israeli flags and lanterns, some called out “shame”.

The anger towards the Prime Minister was so great organisers were criticised for inviting him, an example of the internal pressure on the Leiblers and other Jewish leaders to attack politicians they had spent years building relationships with.

The event was painful for Mr Albanese and other ministers for another reason. Running two-and-a-half-and-a-half hours late, some missed their flights to Canberra, where they had to prepare for a cabinet meeting and parliament. (Ms Wong attended a service elsewhere.)

The last shot

The Jewish community had another senior minister it considered an ally: Deputy Prime Minister and Defence Minister Richard Marles.

Jeremy Leibler had invited Mr Marles to speak at a Zionist Federation conference in Sydney, hoping he could improve the community’s morale. Mr Marles’ mother died a few days beforehand. The Geelong-based politician still showed up on a Sunday, and admitted he had been shocked by the rise in anti-Semitism in a country he had considered, 13 months earlier, a world-class success story in cultural co-existence.

After his speech, Jeremy Leibler complained about two ministers, Jason Clare and Ed Husic, who had accused Israel of war crimes. “There are many in this room looking for hope,” Mr Leibler said. “What can you tell us in response to reassure us?”

Mr Marles would later give a powerful speech to the Sydney Institute that argued opposing Israel’s existence was by definition anti-Semitic. But over the almost six minutes he took to reply to Leibler’s question at the earlier event, he struggled to come up with an answer that satisfied the room of Jews, many wearing yarmulkes. History “will judge Israel,” he said. “It’s hard to say more than that.”

A month later, the government reversed a 20 years of policy and supported a UN resolution calling on Israel to leave the West Bank, a step that would require Mr Netanyahu to relocate more than half a million Jews.

The U-turn

Three days later the Adass Israel Synagogue of Melbourne was firebombed. Although no-one was injured, some considered it the worst anti-Jewish act in Australian history. Jeremy Leibler received a call from Israeli President Isaac Herzog, who expressed concern for Australia’s jews. The Australian Government offered $250,000 to replace the synagogue’s torah scrolls, but Ms Wong did not call him to express sympathy, according to a government source.

The Adass attack was a turning point in Australian attitudes to anti-Semitism. Parliament rallied to the Jewish community’s defence, and introduced mandatory jail sentences for some racially motivated crimes.

But the change came too late for Jeremy Leibler, who must have wondered what was the point of working with the Labor Party’s leadership for years when his people felt abandoned at their most vulnerable.

On February 4, he called out the Government for not assertively repudiating anti-Semitic rhetoric, and tacitly encouraging the demonisation of Israel to protect itself from losing votes to the left.

“Instead of standing firm on its long-held values, Labor has allowed its genuine opposition to antisemitism to be tainted by its political fear of the Greens,” he wrote in The Age. “And in doing so, it has failed the Jewish community at a moment when leadership was needed most. This is not just weakness. It is cowardice.”

Mr Leibler did not mention the prime minister by name, but made it clear Jews -- steeped in 3000 years of conflict -- had washed their hands of Mr Albanese and his Labor Party.

“History will not forget,” he wrote.

On Monday, Liberal leader Peter Dutton promised $35 million to rebuild the Adass Synagogue. On Thursday, he promised that one of his first tasks if elected prime minister would be to call Mr Netenyahu and promise Australia’s support.