JACKSON HEWETT: Taxes will have to rise to pay for the Albanese Government’s profligacy

JACKSON HEWETT: Jim Chalmers may claim that ‘responsible economic management is the hallmark of the Albanese Government’ but there’s only one way to extract Australia from a decade of deficits.

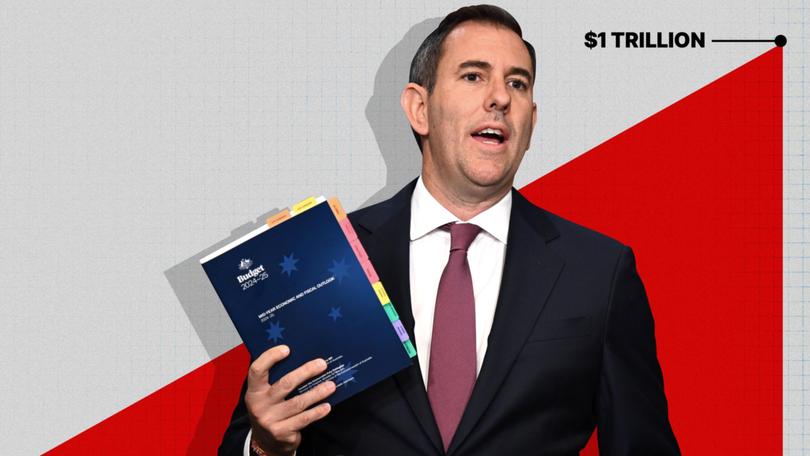

Treasurer Jim Chalmers will go into the election claiming that “responsible economic management is the hallmark of the Albanese Government” but if Labor gets re-elected, will they confess that the only way to extract Australia from a decade of deficits is for taxpayers to foot a greater share of the bill?

Dr Chalmers’ cost-of-living top-ups will add $20b over the next four years. Combined with “unavoidable and automatic” payments for aged care, health care, and pensions, this will require Australia to finance an additional $22b. In waving through such payments, independent economist Saul Eslake said, the only thing the Government has avoided is “making any decisions as to how this additional spending should be paid for”.

If inflation remains elevated, as Trump-era tariffs return, and energy rebates expire, indexing could drive these costs even higher.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.As it is, the public sector share of the economy — health, education and public administration — has hit a record high of 28 per cent of the economy, compared to just 20 per cent 20 years ago.

Looming debt beneath the service

And that is just the official “underlying cash balance” preferred by governments of both stripes.

Turn to page 74 of the Mid-Year-Economic and Fiscal Outlook and the true picture grows worse. That is where all of the off-Budget spending attributable to both parties lie.

If it were a government department, it might be dubbed the “Bureau of Boondoggles,” covering projects like the Snowy Hydro Scheme, the NBN, and the Northern Australia Infrastructure Facility. Theoretically, the projects on the list will deliver a dividend down the track, which is why they also include the HECS/HELP student loans, investments made by the Clean Energy Finance Corporation and and loans under National Reconstruction Fund.

Until they do deliver, they are a cost on the books and reveal that the true deficit — otherwise known as the headline cash balance — is twice as high as the government’s preferred Budget number.

In total there is $90b in spending over the next four years that the Government is glossing over and it has grown $12b since the May Budget. The primary driver is the Government’s hastily constructed plan to waive student debt at a cost of more than $5b over the next four years but there is leakage across the board.

The pernicious use of off-Budget projects to support a Government’s ambitions is fast becoming an economic barnacle.

“It looks increasingly like it’s being used as a means for funding policy in a way which is not as not reported as regularly as the underlying cash balance,” said Stephen Smith of Deloitte Access Economics. “There seems to be an incentive to finance policy off-Budget which is why the headline cash balance is a more accurate measure of the overall health of the of the budget.”

The true picture of the Budget is why Australia’s debt is going to soar past $1 trillion next year and climb towards 40 per cent of GDP.

Budget and off-Budget expenditure growth is why interest will be the fastest drain on government coffers, growing at a 11 per cent per year for the next ten years.

Where, where Budget repair

Australia can no longer rely on China for “unforeseen upgrades” to iron ore tax revenues. China’s urbanisation and industrialisation is nearly complete, and with a declining population needs less and less of the infrastructure stimulus that delivered a $121.9b windfall in the last three years. In the good years, Treasury modelling found that when upgrades occur, they tended to be followed by further upside surprises. Unfortunately for Australia downgrades beget more downgrades.

Clearly, the most effective method to get the deficits down would to cut spending, but Labor has declared more outgoings as “automatic and unavoidable”. The Coalition would have to be ready to burn some serious political capital if it wants to freeze the pension or reduce spending on aged care or health.

“Getting a structural budget deficit back into balance, requires discipline, and it requires spending less than and you take in over an extended period of time. That’s something that we haven’t seen for quite a while in Australia,” Smith said.

If governments don’t make those hard choices, and in the current electoral environment that looks less and like likely, revenue will have to be raised by stealth.

That means increasingly relying on income tax from individuals, which means the Stage 3 tax cuts won’t be enjoyed for long. As wages rise with inflation, more workers will find themselves moving into higher tax brackets.

“With bracket credit, we’ll be back up paying the same overall average rate of tax within a handful of years,” Smith said. That will place a further burden on younger workers, who are already struggling to save to buy a family home.

That leaves budget repair in the hands of actual tax reform, something that both parties have avoided for decades.

Candidate number one is the GST, which means an additional 10 per cent on the price of food, medicine and education.

Smith said that proper tax reform would offset the pain felt by the most vulnerable, but in a cost-of-living crisis, no government would touch it. It would also have an inflationary impact that would need to be managed in concert with the Reserve Bank.

Alternatively, Smith suggests reforming concessional taxation on superannuation contributions and earnings, along with the capital gains tax discount, which disproportionately benefits Australia’s wealthiest. In an era where personal income taxes do more and more of the heavy lifting, the wealthiest among us will be more encouraged to find avenues for tax avoidance, leaving more of the burden on those on median wages.

Finally, Eslake said, an option is to wind back the 2018-19 GST deal done with Western Australia to shore up marginal Coalition seats that has seen $37b “shovelled across the Nullabor.” Cancelling “the worst public policy decision of the Twenty-First Century”, as he calls it, would save $12b at least.

As this election looms, find me a politician who will take on any of these challenging issues. This doesn’t even touch Defence spending or the inevitable rise in costs like the $2.8b already allocated for disaster recovery and biosecurity — both growing priorities in a geopolitically volatile and climate-affected world.

The rest of OECD can attest to how hard making tough choices can be, and what kicking the can down the road looks like.

Gross debt as a percentage of GDP is more than 100 per cent on average across most developed countries with the public tax take ever growing, and populations who revolt at the merest hint of a cut in government handouts.

Alternatively, we decide we want to be like the Scandinavian countries, who have a similar level of debt to GDP as Australia but far higher income taxes to pay for those services.

Either way, someone pays.