Shalom House Diaries: Why Australia’s toughest drug rehab centre fights off cult allegations

‘They can’t be trusted to make their own decisions so we make them for them.’

“How often are you using drugs and when was the last time you used?”

An induction into Shalom House is like an X-ray on your life.

“Have you had or do you have any sexual diseases?”

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.“What debts do you have and who do you owe money to?”

“Who is your GP?”

“Are you on Centrelink and do you have a MyGov account?”

The woman asking me these questions looks like a kindergarten teacher and with good reason. She is one, or was one until her alcoholism took over her life to the point she was drinking hand sanitiser.

Like all the staff at Shalom in Perth’s Swan Valley region, she is a resident. The entire centre is run by the addicts who live there. It’s one of many peculiarities I would discover during my week inside Australia’s toughest drug rehab centre.

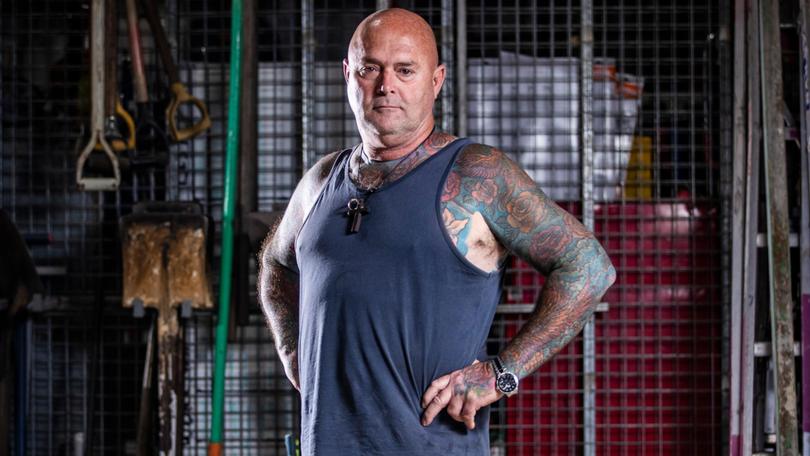

“We need to ask some very personal questions because people’s lives are in our hands and we need to know what we are dealing with,” Shalom House founder Peter Lyndon-James says.

“If someone is coming off heroin they can start fitting all of a sudden so we have to be prepared.

“If they owe money we need to structure a financial plan so they can come out debt-free. We don’t aim to just get them off drugs, we want them to come out of the program in a condition that gives them the best chance of staying clean.

“That’s hard to do if you owe money. We are often dealing with people who have never worked before, some of them have no idea how to cook a meal or do a load of washing.

“It takes a long time to straighten them out.”

He isn’t kidding. The five-stage program takes at least a year to complete and often two.

Residents must cough up $800 up front, which covers their first two weeks, and then $300 a week thereafter. Most pay through their Job Seeker or Disability Support pensions.

For that outlay you get a roof over your head, as much fresh food as you can possibly eat and access to counsellors 24-hours-a-day.

If you need to be clothed you will be — many walk in with nothing save for the shirts on their backs.

Medical care is also provided, including, importantly, dental. The prevalence of “meth mouth” means many addicts have rotten stumps for teeth. Walk around Shalom and will see dozens of people with dentures paid for by the charity.

“It changed my life,” one of the recipients of a new set of teeth, Dayne Pendleton told me.

In return, residents must work every day, either internally or with one of Shalom’s profit-generating businesses. The charity owns a cafe, runs a fleet of removal trucks and operates landscaping and hardscaping divisions.

“Work is central to what we do,” Mr Lyndon-James says. “If you have a health condition that means you can’t do a day’s work then we won’t take you.”

Residents are required to sign a power of attorney form giving Shalom House the legal right to make financial decisions for them.

It is a controversial demand. Critics argue an addict with no options is incapable of giving informed consent.

“They can’t be trusted to make their own decisions so we make them for them,” Mr Lyndon-James says, unapologetically.

“It’s transparent, we have individual trusts for each person’s finances and we are regularly audited. And that level of control is not forever. As they progress through the five stages we give them an amount of their decision-making ability back.”

Stage one lasts a month and sees no outside contact at all. It’s when addicts are most vulnerable because they are coming down.

Phone calls and family visits are allowed in stage two, which usually lasts two or three months.

The third and fourth stages sees residents given a phone (starting with a dumb phone with no internet connection and then an iPhone), shopping for themselves, socialising with friends on the outside and working for a wage either at a Shalom business or with an affiliated company that supports the charity by taking workers on secondment.

Residents who make it to stage five live in their own homes and work regular jobs. Shalom’s mentors check in on them but the only mandatory requirement is the submission of clean urine tests.

Mr Lyndon-James reserves the right to bust people back down if they make mistakes or relapse. And he does.

“I was a level four but sent back to level two,” one ice-addicted primary school teacher explained on my fourth day in.

“I was busted looking at porn on my phone. I had been on free rent as well and I lost that. All up it cost me about $5000.”

He issued a melancholy sigh before ending the story with a deadpan line that had us both laughing.

“It was the most expensive w... of my life.”

The total control Shalom House has over residents is the primary driver of accusations it is a cult.

The shaving of new resident’s heads, a tradition designed to bring everyone back to a level playing field, adds to those suspicions.

Then there’s Mr Lyndon-James’ larger-than-life persona and, of course, the heavy dose of religion.

“We are a faith-based organisation,” Mr Lyndon-James says. “But we don’t ram Christianity down anyone’s throats.”

It might not be rammed but it is ever-present. Every morning starts with 30 minutes of Bible reading, followed by an hour’s group discussion.

There’s a prayer at the start and end of each work day, grace precede evening meals and there are four church services during the week.

It’s a lot of religion and quite confronting for people like this reporter, who can be found on a pew at weddings and funerals only.

“This thing about being a cult is illogical,” Mr Lyndon-James says.

“If people don’t want to be here, I don’t want them here. It’s too destabilising for the rest of them. There are no gates or locks, people are free to leave any time they want.”

They often do. The program is simply too hard for most. The attrition rate is high and only the most committed stay the course.

Tomorrow in The Nightly: Part 3 of the Shalom Diaries. Inside Australia’s Toughest Rehab Centre

Originally published on The Nightly