US President Joe Biden: A 50-year career in politics defined by triumph, tragedy and a reluctant exit

US President Joe Biden will go down in history as a one-term president, the final chapter of his career marked by his failure to put to rest persistent concerns about his mental acuity and physical strength.

President Biden’s momentous decision to drop out of the 2024 presidential race marks the sunset of a consequential career in public service that spanned more than 50 years, during which he traversed the thrills and troughs of American politics while also navigating personal tragedy.

Biden, whose quest for the presidency began three decades before he finally fulfilled it in 2021, becoming the oldest ever to hold the office, is bowing out of politics reluctantly and under pressure, at a moment he has called a critical “inflection point” for America.

The move caps a turbulent journey in Washington for a self-described “great respecter of fate” who tried to protect his legacy by bowing to the conclusion drawn by many Democratic leaders and allies that, at 81 and showing increasing signs of aging, he did not have a viable path to defeating Donald Trump.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.“It has been the greatest honour of my life to serve as your President,” Biden wrote in a letter he posted to social media Sunday.

“And while it has been my intention to seek reelection, I believe it is in the best interest of my party and the country for me to stand down and to focus solely on fulfilling my duties as President for the remainder of my term.”

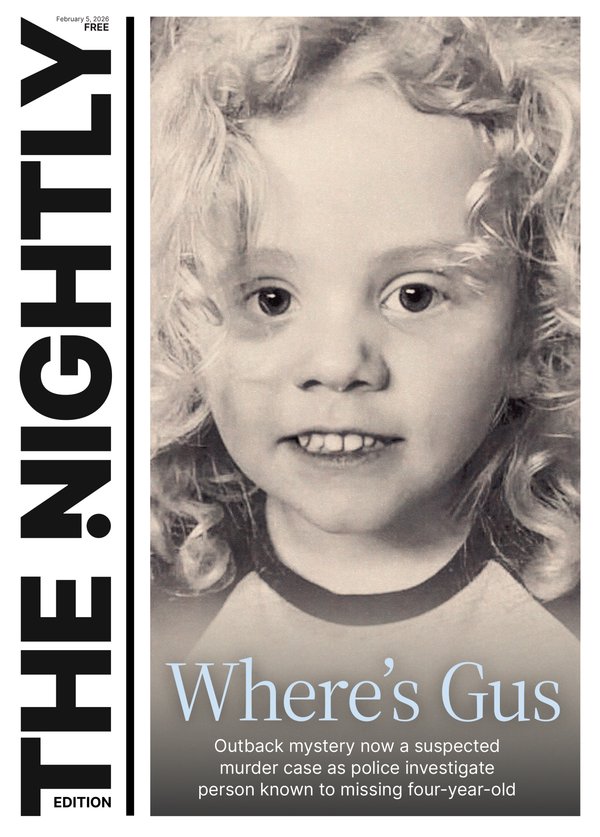

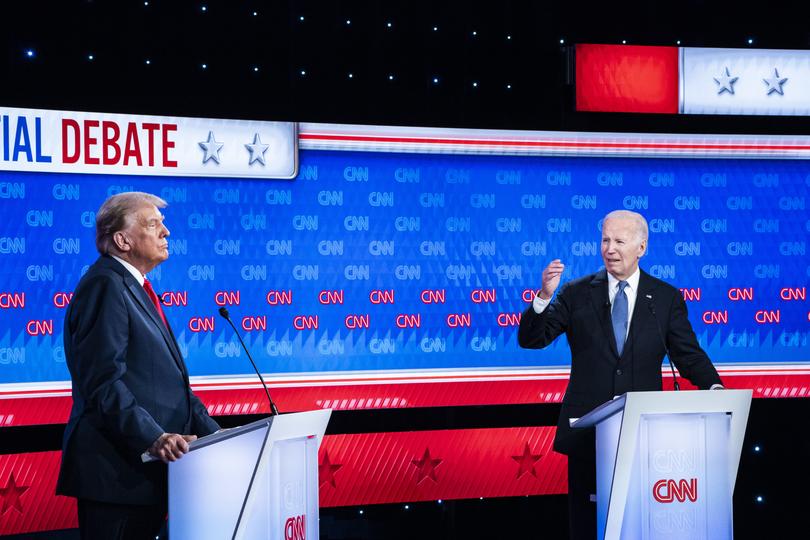

In the end, the doubts that emerged from his halting and politically disastrous performance in the June 27 debate with Trump proved too great for Biden to overcome.

Leaving the race just months before voters cast ballots, Biden becomes the first incumbent president since Lyndon B. Johnson 56 years ago to voluntarily step aside rather than seek reelection.

He will go down in history as a one-term president, the final chapter of his career marked by his failure to put to rest persistent concerns about his mental acuity and physical strength.

Biden ascended from humble roots in Scranton, Pa., a working-class Catholic upbringing that has been central to his political appeal. One of the longest-serving statesmen to occupy the Oval Office, Biden spent 36 years as a U.S. senator from Delaware and eight years as vice president before ousting Trump from the presidency in 2020.

But the time it took to amass that kind of experience contributed to his most existential challenge as president: an advanced age that increasingly dominated the public consciousness as he tried to manage the rigours of the office and of campaigning for reelection.

As questions over his mental fitness and perceived frailty grew, Biden faced low approval ratings and sustained public doubt over his pursuit of a second term that would have ended when he was 86.

While he occasionally was able to quiet those doubts - with strong showings at State of the Union addresses or during daring impromptu visits to war zones - they lingered and burst into the open at last month’s debate.

He struggled to complete his sentences and at times appeared confused onstage, throwing Democrats into a tailspin, with lawmakers, donors and strategists openly warning that Biden would lose in November - and potentially tarnish both his party and his legacy in the process.

Biden was initially defiant, calling his performance at the debate simply a “bad night” and declaring that his cognitive functions remained strong even if his gait and speech had slowed with age.

He spoke of his history of defying doubters, turned to the political base of Black voters and union members that had long propelled his political career, and sought to reframe the battle as one between the middle class and the “millionaires.”

“I’ve got to finish this job,” Biden said at a July 11 news conference. “Because there’s so much at stake.”

With each move, the president drew on the themes of a political career in which he often embraced the role of the odd man out - from boasting of being the “poorest man in Congress” to regularly pitching himself as an avatar for the working class fighting against the elite.

Over the years, Biden developed immense self-confidence by beating odds and overcoming adversities, which helps explain why he insisted in the days since the debate that he would stay in the race and win.

Biden’s career in Washington began after he defeated an incumbent two-term senator and a former Republican governor in 1972, two weeks before turning 30 and becoming constitutionally eligible to serve in the Senate.

He won by about 3,000 votes out of fewer than 230,000 cast, but would never face another close race and would go on to serve six six-year terms.

As he was preparing to be sworn into the Senate after his first election, Biden confronted devastating family trauma that would come to shape his public image.

His wife, Neilia, and infant daughter, Naomi, were instantly killed when a large truck slammed into the Chevy they were riding in. Biden’s toddler-aged sons - Joseph III, known as Beau, and Hunter - were severely injured and had to be hospitalized.

The senator-elect left Washington and returned to Delaware, making up his mind that he would give up the Senate seat to tend to his young boys.

But some sitting senators urged him to take the job temporarily - “just stay six months,” one said - and he agreed. He was sworn in standing next to Beau’s hospital bed.

He ultimately stayed for more than 3½ decades, rising to chair the prestigious Foreign Relations Committee, until Barack Obama chose him to be his running mate in 2008.

Perseverance and empathy forged by overcoming personal tragedy became a key part of Biden’s political brand as he ascended and set his sights on the White House. He often told audiences about a childhood in which he was bullied because of a stutter.

He largely conquered the impediment as he came of age in Scranton and Claymont, Del., though it occasionally reemerged as an adult in politics.

“He is someone who has faced and overcome a lot of adversity,” said David Greenberg, a presidential historian at Rutgers University. “The thought of losing his wife and daughter in a crash that young, I think it’s hard for any of us to imagine, and yet he got himself together.”

Despite being the youngest senator in the country, Biden coveted the presidency from an early age, telling Washingtonian magazine in 1974 that his family expected him to be in the White House “one of these days.”

It would take the better part of five decades for Biden to reach his goal, a pursuit aided by a close-knit family that had long served as his political brain trust, including First Lady Jill Biden, whom he married in 1977.

Biden first ran for president in 1988 and early on was considered a leading candidate for the Democratic nomination. But his bid was rocked by a plagiarism scandal.

The firestorm over news reports that his campaign speeches had lifted passages from other politicians without crediting them was a preview of the kind of frenzy Biden would face as president nearly 37 years later after a faltering debate performance.

Similar to his modern-day response to a campaign in crisis, Biden held a pivotal news conference in 1987 in which he admitted making a “stupid” mistake and tried to turn the page to other matters. But Biden failed to quiet the tumult, and his family and close advisers agreed that he should withdraw.

“There’s only one way to stop the sharks, and that’s pull out,” Ted Kaufman, his friend and chief of staff, told him at the time.

After dropping out of the 1988 race, Biden shifted his focus back to the Senate, where his chairmanship of the Judiciary Committee placed him in a critical position to oversee contentious Supreme Court nominations and shepherd pivotal legislation dealing with crime, guns and domestic violence.

Biden’s next run for the presidency, some 20 years later, would also embody the kind of turbulence that has dominated his political career. He struggled to overcome a series of early gaffes and faltered in the 2008 Iowa caucuses, receiving less than 1 per cent of the vote.

Biden immediately withdrew from the race, which was being dominated by two more famous of his Senate colleagues, Obama and Hillary Clinton. But his goals of getting to the White House were resurrected months later when Obama secured the nomination and asked him to become the vice-presidential nominee.

Biden initially declined the offer, but Obama asked him to talk it over with his family, Biden recounted in a 2023 interview with comedian Conan O’Brien.

“Let me get this straight, honey,” Biden recalled his mother saying when he told her about the offer. “The first Black man has a chance to be president, he says he needs you, and you told him no?”

Biden found the argument convincing. He joined the ticket with Obama, who went on to defeat Republican Sen. John McCain that November.

During eight years as vice president, Biden played a crucial role as a liaison to Congress and as the last adviser in the room ahead of crucial decisions, particularly on foreign policy.

He celebrated Obama’s highest moments - famously declaring the passage of a landmark health-care bill a “big f---ing deal” - while also commiserating after Republicans captured both the House and Senate in devastating midterm elections for Democrats.

Near the end of his second term as vice president, Biden faced another family tragedy when his son Beau, then Delaware’s attorney general, who was celebrated as a potential future candidate for national office, died of brain cancer in 2015 at age 46.

Beau’s death would loom large over Biden’s political future, as he faced multiple decisions about whether to run for president in the ensuing years.

Biden considered mounting a bid for the nomination in 2016, but ultimately decided against it, publicly citing his grief over Beau’s death and privately grousing over the fact that Obama and other Democratic leaders had sidelined him in favor of Clinton.

Trump defeated Clinton that November, leading Biden to conclude he would have fared better and regret his decision not to run. This increased his resolve to rely on his own instincts going forward and motivated him to run to defeat Trump in 2020. That “inner confidence” came into play as Biden faced a wave of calls to drop out of the 2024 race in the aftermath of the debate, Kaufman said.

“He’s been president of the United States and vice president, and spent 36 years as United States senator,” Kaufman said in an interview weeks before Biden dropped out. “He doesn’t get flummoxed by what individual people say about what he should do.”

Biden was initially reluctant to believe polls and pundits suggesting he would lose to Trump this November, in part because of his experience in the 2020 election.

He had begun the Democratic primaries that year with brutal losses, placing fourth in Iowa and fifth in New Hampshire. But he continued on to more diverse states, winning a resounding victory in South Carolina thanks to broad support from Black voters that breathed new life into his candidacy.

“He developed a narrative of himself as someone who people count out and to then comes back,” Greenberg said.

Biden went on to win the Democratic nomination and defeat Trump in the general election to become the nation’s 46th president. His vice president, Kamala D. Harris, made history as the first woman, Black person and Asian American to hold the role.

He received more than 81.2 million votes, the most of any presidential candidate ever, though the electoral college was so closely contested that a shift of fewer than 45,000 votes across three states would have swung the election to Trump.

Biden was reluctant to leave the race this summer because he had “spent his whole life trying to get there,” said Chris Whipple, author of “The Fight of His Life: Inside Joe Biden’s White House.”

Like much of his political career, Biden’s presidency has been a study of contrasts. He successfully advanced major legislation on infrastructure, climate change and economic recovery. He oversaw the creation of 15 million jobs and helped restore vital global alliances.

At the same time, however, he suffered historically low poll numbers, driven by a chaotic 2021 withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan, stubbornly high inflation, record migration at the southern border and lingering concerns over his age.

Biden had ascended into office declaring himself a transitional leader of the party and pledging to be a “bridge” to the next generation of Democratic leaders.

But he put any doubts about whether he would serve a single term to rest when he announced a bid for reelection after his party performed well in the 2022 midterm elections.

His decision to drop out of the race so late in the campaign cycle ensures that his presidency will be remembered as transitional - though the outcome of the election could determine what that transition ultimately leads to.

Biden’s decision conjures up memories of Johnson, a Democrat who opted against running for a full second term in 1968, stepping aside after achieving successes on domestic policies but under pressure over his handling of the Vietnam War. Johnson’s vice president, Hubert Humphrey, ended up losing to Republican Richard M. Nixon in an electoral college landslide, an outcome Biden is now working to avoid in the race to stop Trump.

With his legacy hanging in the balance, Biden must turn his energy towards bolstering another candidate against a man he has called an existential threat to democracy.

Before leaving the race and stepping aside from a lifetime of public service, Biden was asked what it would mean if he stayed in and lost to Trump.

“I’m not in this for my legacy,” Biden said at the July 11 news conference. “I’m in this to complete the job I started.”

© 2024 , The Washington Post