LATIKA M BOURKE: Peter Dutton’s back to the future foreign policy and its pros and cons

Peter Dutton’s foreign policy blueprint bets that he can wrangle an increasingly capricious Donald Trump simply because the Coalition did so in the US President’s first term. It’s a risky gamble.

Peter Dutton set out his foreign policy blueprint in a major speech in Sydney this week, leaning into one of his areas of natural strength ahead of an election that will overwhelmingly be fought on the cost of electricity, rents, mortgages and groceries.

The Opposition Leader landed some decent blows on the institutionalised yet “inexperienced” Prime Minister Anthony Albanese who, despite spending 26 years in Parliament has not only floundered in foreign policy but disturbingly shows little interest in trying to complement his obvious and damaging deficiencies in the area.

So Mr Dutton, a former defence and home affairs minister, was on much more comfortable and authoritative ground when he pledged that his priority would be national security.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.But his foreign policy blueprint contained frequent doses of nostalgia and rests heavily on the notion that he can wrangle the increasingly capricious Donald Trump because the Coalition was able to navigate the first Trump Administration.

“The best indicator is past performance,” Mr Dutton said.

“I have worked successfully with the Obama Administration, the Trump Administration Mark I, and the Biden Administration.

“I do believe that, if there’s a change of government, I will be able to work with the Trump Administration Mark II to get better outcomes for Australians.”

This is a gamble at best when it come to the steel tariffs the Trump administration is determined to impose on Australian producers - an outcome which the Coalition consistently blames the Albanese government for failing to prevent.

This second Trump Administration is far more ideological. It is destructive and exhibiting its protectionism in systematic ways it did not in its first iteration.

Indeed, on the steel and aluminium duties, Trump-land views its first-term benevolence as a mistake and with some key advisers on the issue, like the White House’s senior counsellor for trade and manufacturing, Peter Navarro, when it comes to China-reliant Australia, the tariffs get personal.

“Consider Australia,” Mr Navarro recently wrote in USA Today.

“Its heavily subsidised smelters operate below cost, giving them an unfair dumping advantage, while Australia’s close ties to China further distort global aluminium trade.”

Australia is and can keep trying to extract an exemption but the mood music is not good and that is not the fault of Labor.

Nevertheless, tariffs aside, Mr Dutton is right to prioritise the relationship and show a willingness, unlike Mr Albanese, to actually establish a relationship with Trump through an early visit.

Whilst Australians understand that the change in the Australia-America relationship has come from the US side and not the other way round, the UK’s Labour Prime Minister Keir Starmer has shown the value of at least paying a visit to the White House having subsequently used the relationship he built to smooth things over between Mr Trump and Ukraine’s President Volodomyr Zelensky after the ugly February 28 Oval Office blowup.

As has been his tendency when difficulties arise on the international stage, Mr Albanese has appeared frightened, and or complacent and preferred to retreat to Australia’s distance and size to justify his insularity and disinterest, deferring any requests to visit the United States to the Quad leaders summit later this year.

If Mr Albanese is re-elected he will go into that Quad meeting as the only leader not to have paid a visit to the White House, so Mr Dutton’s approach is welcome.

But on foreign aid, Mr Dutton was inconsistent, having failed to rule out copying UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s model of cutting international development to pay for a desperately-needed increase in defence spending, while also suggesting he could persuade the Americans to un-DOGE Pacific aid spending.

When it came to Europe, Mr Dutton ruled out, unquestioningly, the notion of Australia contributing to any peacekeeping mission to secure Ukraine’s future, citing Australia as an under-resourced “middle power” incapable of operating in more than one theatre.

“There is no United States assurance about providing an overlay … the United States has said that they won’t have a presence,” Mr Dutton said.

The Trump Administration is indeed cold on the idea of acceding to Europe’s request that it provide a security assurance in Ukraine – it is desperate to restore economic ties with Russia.

Unlike Australia and Europe, it does not view the conflict as about protecting sovereignty and the idea that big countries should not be allowed to invade smaller ones and get away scot-free, instead believing that it is a conflict that Ukraine and NATO provoked.

Mr Dutton, who said his foreign policy should be “underpinned by moral clarity,” should be wary about sending a signal that our security is so closely tied to the United States that we do not posses the autonomy to make decisions based on our values particularly when they clash so clearly with those held by this version of America’s.

As Australia’s former ambassador to Russia recently told The Nightly, a values-based reason to offer support to France and Britain’s Coalition of the Willing “also matters to us because it matters to countries that matter to us”.

Mr Dutton, unlike his conservative counterpart in New Zealand, has not even been open to considering what Australia might be able to contribute or learn from the brave Ukrainians, as Britain and Europe try desperately to stop the second Trump Administration junking a world order that has benefited Australia.

However, he still promises that a “Coalition Government will always stand with our friends and allies in their darkest hours when they face tyranny and terrorism.”

He is right that the mission is ill-defined and unclear, it is a work in progress but a moral foreign policy isn’t one if it is selectively applied.

His Europe policy was also defined by seeking to renew a trade agreement that the Coalition failed to secure when last in government and Brussels has all but shelved after talks collapsed under Labor over the EU’s limits on how much Australian beef it would sign.

This makes any fresh attempts for an Australian deal even less likely in the Europe and given that the Coalition has repeatedly set tests for Labor that any agreement struck must not sell out farmers, it’s impossible to see Mr Dutton believes he will be more successful in persuading the protectionist Europeans or French to bend.

Either Mr Dutton is going to have have to ask Australian beef producers to accept lesser access than they’d like for improved opportunities to the Euope’s enormous market elsewhere, or he can consign that idea to the wish-list as well.

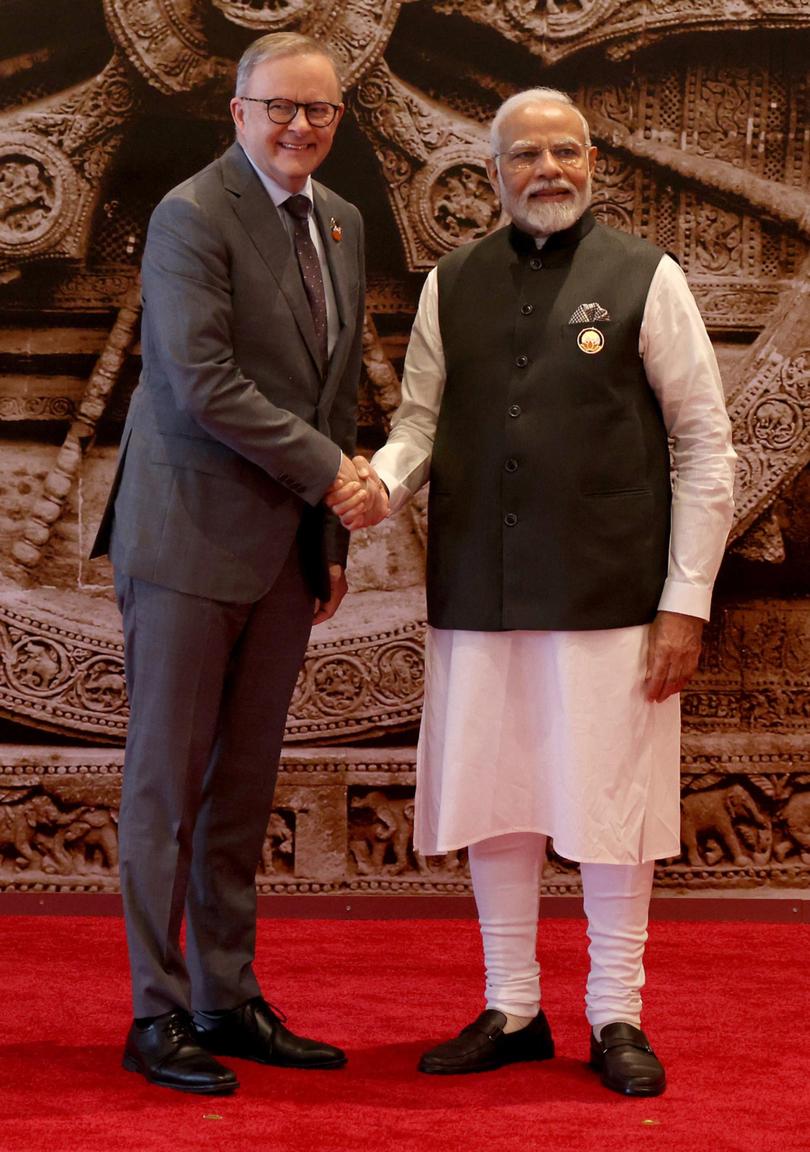

While there was much to like in Mr Dutton’s speech, particularly his promise to take a firmer line against Chinese displays of aggression and commit to higher defence spending — once again, figures to be revealed during the campaign it — was staggering to see the Coalition leader completely omit India from his strategic thinking.

He listed the US, Indonesia, Japan and the UAE as priority relationships.

In a world where the US and China are behaving like each other, India is an obvious third-way option for Australia.

We already have extremely strong people-to-people links with the world’s most-populous nation and growing defence ties underway, so to completely ignore India’s rise as part of our foreign policy is inexeplicable.

We should be throwing everything we have into growing this relationship, through the Quad as well as bilaterally, given the Trump Administration has singled out the grouping that also includes Japan for priority as a way of trying to contain China’s attempts to dominate the region and control of our shipping lanes, upon which our export economy depends.

By failing to even mention the role India can play in our foreign policy, Mr Dutton showed he still has some work to do in updating his back to the future approach to Australia’s strategic and future place in the world.