ExThera Medical: A startup claimed its device could cure cancer. Then patients began dying

Two US companies teamed up to treat cancer patients using an unproven blood filter in Antigua, out of reach of American regulators. Then things took a tragic twist.

The private jet took off from the Caribbean island of Antigua in April carrying three highly combustible tanks of compressed oxygen and a terminally ill cancer patient.

Kim Hudlow had chartered the plane for her husband, David. She crouched by his side on the five-hour journey to Florida, frantically adjusting the valve on one of the oxygen tanks as he struggled to breathe. A doctor had just told her he was dying. She was terrified he wouldn’t survive the flight.

It was an abrupt turnaround. Six days earlier, Kim Hudlow and her husband, who had late-stage esophageal cancer, had arrived on the tropical island full of hope that a novel blood-filtering treatment offered there would save David Hudlow’s life — or at least prolong it.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.They were among about two dozen families lured to Antigua by a California startup called ExThera Medical and its secretive billionaire partner, Alan Quasha.

ExThera, which has about 50 employees, makes a single product: a filter that it says can be used to remove the tumor cells that circulate in patients’ blood and enable cancer to metastasise. Early last year, the company sold thousands of the devices to Quasha’s private equity firm, Quadrant Management, which began using them on late-stage cancer patients at a small clinic in Antigua.

Quadrant, which invests on behalf of Quasha and his family and doesn’t have outside investors, charged $45,000 for each course of treatment and advised patients to return to the clinic for regular sessions. It also urged them to abstain from chemotherapy between treatments.

ExThera and Quadrant promoted the blood filtering to the Hudlows and other couples by citing a Croatian study of patients with metastatic cancer that they said had yielded extraordinary results, according to phone recordings obtained by The New York Times.

In one call with the Hudlows, John Preston, an ExThera board member and longtime business partner of Quasha, claimed that three patients in the study had been cured of their cancers. During another call, Dr. Sanja Ilic, ExThera’s chief regulatory officer, told Kim Hudlow that one of the study’s patients had recovered from inoperable colon cancer to such an extent that he was training for a marathon.

“I don’t know of any other treatment available in the world, on this planet, that can do better stuff,” Ilic told Hudlow.

But those statements have yet to be backed up by any published data, and the Croatian study — with only 12 participants — was too small to draw any reliable conclusions, according to the doctor who conducted it. There is no data from a human clinical trial showing the device slows or reverses cancer.

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration has authorized ExThera’s blood filter for use only in emergency COVID-19 cases. The filter appears to work well for that purpose, having been administered successfully to hundreds of severely ill patients infected with the coronavirus.

Last summer, the FDA allowed ExThera to test the filter on five pancreatic cancer patients in Oklahoma — the first phase of what is likely to be years of clinical trials to seek the agency’s approval to use the filter to treat cancer.

By carrying out the treatments in Antigua, where the FDA has no jurisdiction, ExThera and Quadrant circumvented that long, drawn-out regulatory process. But Preston and Ilic may have nonetheless violated federal law by promoting ExThera’s filter to American cancer patients on U.S. soil.

In February, two months before the Hudlows’ ill-fated trip to Antigua, Jonathan Chow, ExThera’s director of medical affairs, warned the company’s top executives in a letter that the Antigua operation amounted to an unethical and unsafe experiment on patients and urged them to shut it down, according to three people familiar with the matter. During a brief visit to the island, Chow had witnessed patients bleeding from catheter wounds and screaming in pain. ExThera didn’t act on his pleas.

More than 600,000 Americans die of cancer each year. For all the medical advances achieved in recent decades, the number of therapies offered to patients whose cancer has spread to multiple organs remains limited. In most cases, the standard of care is still chemotherapy and radiation, which can buy patients time but rarely cures them.

Patients with grim prognoses are often willing to try anything that might offer hope. And plenty of providers — many of them operating in countries with regulations less stringent than those in the United States — are willing to seize on that desperation.

Some patients have sought treatment from a doctor in Austria who says he will cure them with a machine he built underground that supposedly restores “balance” to cells. Others have gone to Mexico for injections of immunotherapy drugs straight into their tumors. Like the blood-filtering sessions in Antigua, these treatments are expensive and not covered by insurance, saddling patients and their families with enormous out-of-pocket costs.

But ExThera and Quadrant seemed to offer more credibility than the usual offshore clinic. ExThera is a U.S. company with an FDA-approved device, albeit not for the purpose it was being touted. Quadrant, too, is a U.S. corporation, run by a wealthy investor with a successful track record. The treatment the companies were marketing was experimental, but its promoters had the veneer of legitimacy.

In hindsight, Kim Hudlow said, the possibility of a miracle cure acted on her “like a drug.” She added, “I feel so duped by all these people. The way this was spun up and the way it was explained, they got me.”

Quasha said in an email that Quadrant “made no recommendations for what therapies patients should receive.” Patients opted for the filter treatments on their own in consultation with their doctors, and the company took care to remind them “at multiple steps in the process” that the therapy was experimental, he said. He and Quadrant declined to address the specifics of David Hudlow’s or any other patient’s case.

Of the more than 20 patients treated in Antigua, the Times has identified at least six who have died since their treatments. However, one patient, a woman from Oklahoma, did appear to benefit from the blood filtering. Her husband said that the treatments provided her significant relief from her pancreatic cancer pain and that she no longer requires any pain medication.

After the Times sent ExThera a list of detailed questions, the company said it asked Preston to leave its board and told its employees it had parted ways with Ilic. It also said it terminated its partnership with Quadrant. ExThera did not elaborate on the reasons, but Quasha said it was a mutual business decision and “had nothing to do with our belief in the efficacy of the filter treatment.”

Despite the split, Quadrant says it continues to treat cancer patients in Antigua with ExThera’s devices. Quadrant has several thousand filters stored at a warehouse on the island.

A Military Origin

ExThera’s blood filter came out of a military contest. In 2012, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, the Pentagon department behind early versions of the internet, solicited proposals for a new medical device that would remove pathogens from blood. The goal was to deploy it in the field to treat soldiers exposed to infections or biological agents.

ExThera, founded in the San Francisco Bay Area by two chemical engineers, won the contest with a 3-by-9-inch transparent cylinder containing more than 20 million tiny beads. The beads are covered in heparin, a substance similar to a molecule found inside blood vessels that pathogens bind to. When blood flows through the device, the beads mimic the inner walls of blood vessels and capture viruses, bacteria and fungi. The device works in tandem with a dialysis machine, which pumps blood out of a patient’s body and into the device before returning it, filtered of pathogens, to the patient.

The European Union approved ExThera’s filter, which the company christened the Seraph 100 Microbind Affinity Blood Filter, to treat bloodstream infections in August 2019. When the pandemic reached U.S. shores six months later, Army doctors tried it on two critically ill COVID-19 patients. The patients’ viral counts plummeted, and both recovered. The FDA subsequently approved the device for use on COVID patients on the cusp of respiratory failure. ExThera says its Seraph filter has since been used on thousands of U.S. and European patients with COVID or bloodstream infections.

But as the pandemic ebbed, ExThera’s sales to hospitals peaked at a few million dollars and then began to decline. The company began looking for new uses for its filter. One idea was to see if the heparin beads could also capture the tumor cells that float in cancer patients’ blood. Known as circulating tumor cells, or CTCs, they play an important role in enabling cancer to metastasize.

The initial signs were encouraging: A small German laboratory study showed that, at least in test tubes, CTCs attached to the heparin beads.

ExThera took the research a step further in the spring of 2023. Ilic, who had worked at major medical device companies before becoming ExThera’s chief regulatory officer, met a Croatian doctor named Vedran Premužić at a conference in Zagreb, and over dinner at a seafood restaurant, they decided to test the filter on cancer patients, according to a person familiar with the matter.

The study began with eight patients in September 2023 and later expanded to 10 and then to 12 patients. Normally a study to gauge a device’s effectiveness at treating cancer would be run by an oncologist, but Premužić wasn’t a cancer expert. He specialized in kidney diseases.

In December 2023, Ilic discussed promising early findings from the study with ExThera’s top executives, including results for a lung cancer patient whose tumor appeared to have shrunk and several patients whose biopsies had come back negative, according to a person with knowledge of the matter.

A few days later, Preston, the ExThera board member, informed the company that he knew someone who was interested in becoming its partner in the Caribbean. It was Quasha, with whom Preston had worked on private equity deals for 15 years.

Quasha had deep pockets. Over 4 1/2 decades, he had quietly built a fortune buying up companies and restructuring them. One of his early acquisitions was a Texas oil firm whose chair was the future president, George W. Bush.

Following Preston’s introduction, ExThera shared the Croatian cancer data with Quasha. Impressed, he invested $3 million in the company.

He also created a subsidiary of his investment firm called Quadrant Clinical Care and appointed his daughter, Dr. Devon Quasha, a physician at Mass General Hospital in Boston, as one of its executives. Quadrant Clinical Care paid ExThera an additional $10 million — several times what ExThera was generating in annual revenue — to become its Caribbean distributor.

A ‘Dubious Foreign Operation’

In early January 2024, Ilic and another ExThera official loaded a dialysis machine and hundreds of filters onto Quasha’s private jet at an airport in San Diego and flew them to Antigua. On the way, the jet made a refueling stop in the Bahamas, where it picked up Quasha. Chow, ExThera’s director of medical affairs, followed on a commercial flight two days later.

Quadrant had contracted with a local clinic to begin administering the treatment. The ExThera team was traveling to the island to teach the clinic staff how to use the filter. Unlike the FDA, the government in Antigua had authorized Quasha’s firm to use the device on cancer patients.

The operation had the potential to be lucrative. Quadrant was paying ExThera around $1,000 per filter, according to a person with knowledge of their contract, and three filters would be used per treatment regimen in Antigua. With a $45,000 price tag for patients, the profit margins for Quadrant could be huge.

But when the ExThera employees arrived in Antigua, some of them quickly grew worried.

The clinic Quadrant had hired lacked modern medical equipment, and the doctor in charge, a surgeon named Joey John, was making incisions under some patients’ collarbones to install dialysis catheters without using any medical imaging or sufficient anesthesia, according to two people familiar with what the ExThera team encountered. Chow witnessed patients bleeding profusely and, in one case, screaming in pain. He was also alarmed to learn that a patient was forgoing chemotherapy, a pillar of cancer care, for an experimental treatment.

ExThera had flown in Sarah Mobbs, a nurse who had experience treating COVID patients with the filter, to help administer the therapy. Company officials had told Mobbs that she would be assisting with a cancer study. But when she arrived at John’s clinic, she saw no signs of the guardrails that would normally accompany a clinical trial, three people with knowledge of the matter said. There was no treatment plan, no oversight from a medical board to ensure the supposed study was conducted safely and ethically. There wasn’t even an oncologist on site.

Mobbs later told associates that her unease grew when she overheard Ilic tell cancer patients that the filter would cure them, the three people said. She worried Ilic was giving them false hope. To extricate herself from the situation, she made up a story that her mother and daughter had been in a car accident and left the island in a hurry.

Ilic said she shared some of Chow’s and Mobbs’ misgivings. But she denied telling any patients that the filter treatments would cure them.

Chow voiced his concerns to Erin Borger, ExThera’s CEO, and others on several video calls, according to someone with knowledge of the conversations. He then sent Borger and Robert Ward, one of ExThera’s founders who was also chair of its board, a letter outlining his worries. In the absence of data supporting the use of the filter to treat cancer, the company was taking “undue risks” with patients and subjecting them to “human experimentation,” he wrote. Referring to the Antigua clinic as a “dubious foreign operation,” he urged ExThera to end its association with it.

But ExThera continued providing Quadrant with filters and the treatments in Antigua continued. Frustrated that his warnings were ignored, Chow resigned from ExThera in June.

Asked about Chow’s letter, Borger said: “We take matters of safety and workplace conduct very seriously. When these issues arise, we immediately investigate the matter and take appropriate action.” He declined to say what, if any, actions had been taken. Ward declined to comment.

The Cancer Wives Club

Nearly a month after Chow began airing his complaints inside ExThera, Preston, the board member who had introduced the company to Quasha, spoke by phone with the Hudlows and Jaime Baskin.

Kim Hudlow, who lives in Panama City, Florida, and Baskin, an elementary school special ed teacher in Chicago, had met 18 months earlier through a common friend. Baskin’s husband, Brian Withey, was eight years younger than the 55-year-old David Hudlow, but they both had metastatic cancer. Withey’s had started in his rectum and spread to his liver.

Along with the wives of three other cancer patients, Hudlow and Baskin had formed what they jokingly referred to as “The Cancer Wives Club,” texting and calling one another daily to lend emotional support and share new medical insights.

One member of their group had heard about ExThera and its blood filter through a friend who had breast cancer and had been treated — unsuccessfully, it would turn out — in Antigua. Intrigued, Baskin arranged a call with Preston. The Hudlows dialed in from Florida.

It is illegal in the United States to promote a medical device or a drug for a use that has not been approved by the FDA. Yet that is precisely what Preston did, according to a recording of the call.

Preston began by explaining the filter’s origin and the science behind it. By eliminating circulating tumor cells from patients’ blood, he said, the filter freed up the immune system to attack the tumor itself. (There is no published clinical data to support this theory.) Preston then brought up the Croatian study and said that four of its eight patients were “doing well” and that another three seemed “to be fully recovered from their cancer.”

When Baskin asked what he meant by “fully recovered,” Preston replied: “We can’t find it, I’ll put it that way.”

Preston also mentioned three metastatic cancer patients whose blood had been filtered in Antigua the previous month. He said the change in how those patients felt after their treatments was “remarkable.” One patient — the woman from Oklahoma — was doing so well that she no longer needed her pain medicine, he said.

The call with Preston lifted the hopes of the Hudlows and Baskin. But the reality was not as promising as Preston had implied.

In an interview with the Times in September, Premužić, the nephrologist conducting the Croatian study, said it would be “highly suspicious” to describe the filter treatment as effective at such an early stage of research without larger randomized clinical trials. He said that while his study had produced encouraging results, it was too small to reach any firm conclusions.

In November, the journal Blood Purification published a short paper about the study online. The paper said that the number of circulating tumor cells measured in 10 patients treated with the filter declined by a median of 71% during the treatment. But it said nothing about how the patients fared longer term and made no mention of three patients being cured of their cancers. Premužić did not respond to follow-up questions after the paper was published. Ilic, who is a co-author with Premužić on the Blood Purification paper, said more papers based on the Croatian study are forthcoming.

Preston said in an email that his communications with the Hudlows and Baskin were “true and accurate to the best of my knowledge” and took place “at the request of the treating physicians.” But Baskin said no doctor was involved in setting up the call.

Kim Hudlow, who had been a nurse before she started a roofing business with her husband, decided to do some of her own research. She spoke with Ilic, who talked in glowing but vague terms about the Croatian study. She also learned that Dr. Mark Rosenberg, a Boca Raton, Florida, oncologist who had previously consulted on her husband’s care, was referring patients to Antigua. She reached out to him.

Rosenberg told Hudlow that he didn’t have much data to go on but that patients who had undergone a filtering session felt “amazing” afterward, according to a recording of one of their calls. He also told her that Ilic had shared with him scans showing that a patient’s lung tumor had shrunk 80% within three weeks of being treated with the filter.

“If this is true, what we’re seeing, this is the most exciting advance in oncology ever,” Rosenberg told Hudlow.

Rosenberg has since changed his view. In an interview, he said he stopped referring cases to the Antigua clinic months ago because he didn’t see any positive results among his patients. He said Ilic never shared any data with him beyond the scans he mentioned to Hudlow. In the absence of data, “it’s difficult to know what’s real and what’s not real,” he said.

As an ExThera employee at the time, Ilic said she was not authorized to share clinical data with company outsiders.

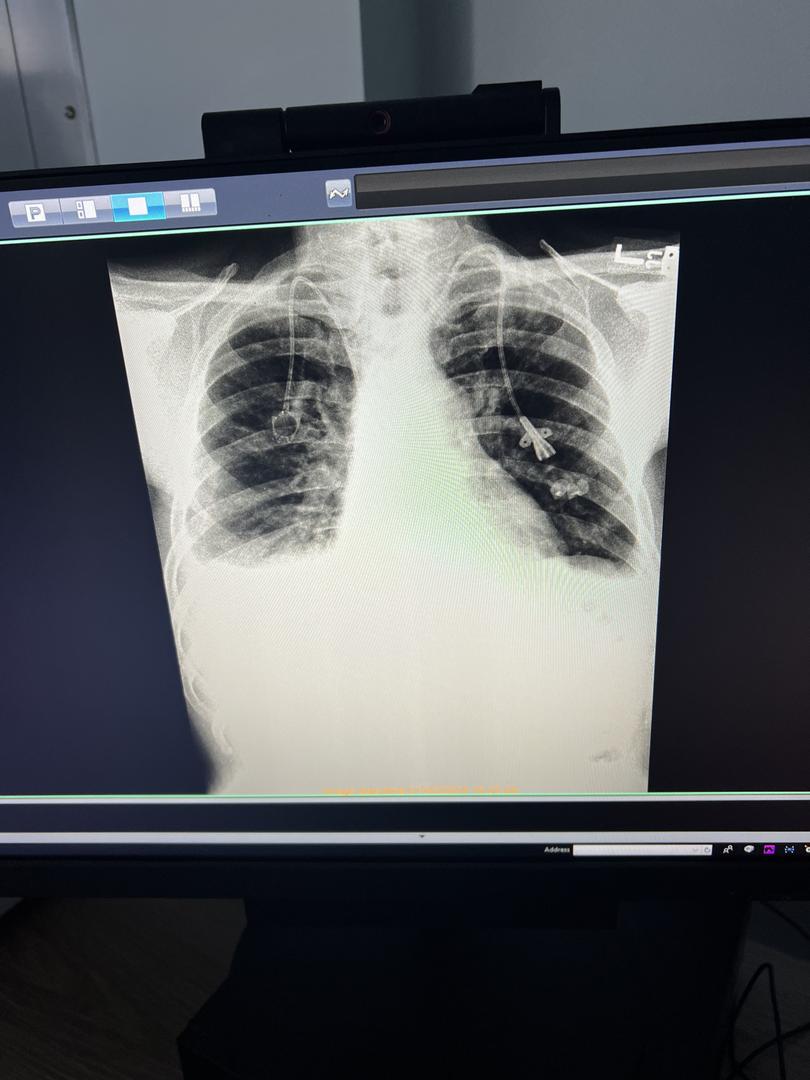

The Times reviewed the scans — showing a patient’s lungs before and after treatment — that Ilic showed Rosenberg. The post-treatment scan does appear to show a smaller tumor, but the angles and scales of the two images are different, which makes it difficult to tell whether the tumor actually shrank.

Hudlow doesn’t begrudge Rosenberg for his change of heart. But at the time, his enthusiasm helped sell her on the treatment. After talking things over with her husband, she contacted Tom Pontzius, the president of Quadrant Clinical Care, to make an appointment and wired $45,000 to the company. On Feb. 27, she and David Hudlow flew to Antigua.

When they got to John’s clinic, Kim Hudlow’s trained nurse’s eye picked up on things that bothered her. The nurses weren’t washing their hands. The surgical scissors they were using to cut away the dressings around patients’ catheter wounds weren’t sterilized. And one of the patient rooms didn’t have a machine to monitor vital signs. But, she said, she tried to remain upbeat for her husband’s sake.

Over the next seven days, David Hudlow underwent three filtering sessions. Afterward, his wife said, he felt weaker, and his pain increased.

Soon after the Hudlows returned to Florida, there were signs that his cancer was growing more aggressively. A test called Signatera showed that the amount of cellular tumor DNA in his blood rose nearly sixfold. As she was cutting his hair one day, Kim Hudlow noticed an ugly-looking growth on his back. Soon, another one appeared on his ear, followed by one on his scalp. They were skin tumors.

David Hudlow was also having difficulty breathing. His wife took him to the emergency room, where he was diagnosed with a pleural effusion — a buildup of fluid in the lining of the lungs. Doctors tapped his lungs and drained a liter of reddish-brown liquid.

Kim Hudlow wondered whether her husband should get back on chemotherapy, but Preston, the ExThera board member, had advised against it on their call. He had said that chemotherapy worked at cross purposes with the filter by weakening the immune system.

She called ExThera’s Ilic for advice. Ilic said that if David Hudlow felt worse after the filter treatments, it was a good sign, according to a recording of the call. It meant that he “had strong immune activation,” Ilic said.

Ilic dismissed the Signatera test because she said it didn’t differentiate between live and dead cancer cells. Quadrant had said it would send samples of Hudlow’s blood to a lab in Germany to measure the change in his circulating tumor cells. That CTC test was the one to pay attention to, Ilic said.

Kim Hudlow was still looking for more evidence that the treatment worked, so she inquired again about the Croatian study. Ilic said its data was “amazing,” and she repeated something she’d mentioned once before: The tumor loads of the patients in the study had shrunk by a minimum of 49% six to eight weeks after their treatments. Hudlow was in awe. “Wow, that is just, that’s just unbelievable,” she said. (There is no evidence of this in the Blood Purification paper.)

Even so, Hudlow sensed that there were simmering tensions between Ilic and Quadrant. After three weeks of waiting for results of the CTC test, she had contacted the German lab directly and learned that Quadrant had bungled the blood shipment. Her husband’s samples had arrived there coagulated and useless. When Hudlow told Ilic about the mishap during another call, Ilic called Pontzius, the Quadrant Clinical Care president, a “total idiot” who didn’t understand medicine.

But in the next breath, she gave Hudlow new hope, the recording of that call shows. She had previously mentioned a “Patient No. 4” from the Croatian study with inoperable colon cancer whose condition was similar to David Hudlow’s. That morning, Ilic said, she had learned that 60% of Patient No. 4’s tumors had disappeared. In fact, the patient was doing so well that he was training for a marathon, she said. (There is no mention of this in the Blood Purification paper.)

Ilic then confided to Hudlow something that she asked her not to repeat to anyone: British doctors had contacted her to discuss the filter in connection with the care of Catherine, Princess of Wales, who, Ilic suggested, had colon cancer.

A person with knowledge of the princess’ medical care said that was not true.

Three Husbands in the ICU

Hearing about Patient No. 4’s recovery persuaded the Hudlows to return to Antigua for another round of treatments. They flew there on April 3. David Hudlow’s health had declined sharply, but he was still able to walk on his own.

Baskin and Withey were to fly in from Chicago four days later, on April 7. They would be joined by another member of the Cancer Wives Club, Stacey Bowen, and her husband, John Bowen, who had colon cancer.

Baskin had been in contact with Ilic, too, but what had really sold her on the treatment was the call with Preston and his description of the three Croatian patients’ full recoveries. The same was true of the Bowens.

By the time the two other couples arrived on the island, Hudlow was in bad shape. During the second of his three scheduled filtering sessions, his pulse had quickened and he had begun gasping for air. The nurses transferred him to a small intensive care unit on the other side of the building.

Tests showed that his blood counts were dangerously low, so John, the doctor, ordered a blood transfusion. But that didn’t help with his breathing. Hudlow spent three nights in the ICU on intermittent oxygen.

On April 8, John offered a grim prognosis: He told Kim Hudlow that her husband was dying. John was traveling to Miami for a conference the next day and recommended that they get on the same commercial flight. If David Hudlow struggled to breathe onboard, John said he would declare a health emergency and pull down the oxygen mask from the panel above his seat.

That sounded like a terrible idea to Kim Hudlow. On their last call before leaving Florida, Ilic had called John “a cowboy” and his clinic “the Wild West.” Hudlow now wished she had taken her words more seriously.

Hudlow tried instead to arrange an air ambulance to the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Florida, where her husband had been treated before. But Mayo told her it couldn’t accept an international transfer. Running out of options, she pleaded with John to sell her oxygen tanks and then started dialing charter jet companies. Three pilots turned her down before she found one who agreed to fly with the oxygen tanks aboard.

In the meantime, John Bowen and Brian Withey had begun their own filtering treatments. After his first session on April 8, the incision John, the doctor, had made in Bowen’s groin to insert his dialysis catheter began oozing blood. In the next room, Withey’s blood clogged three filters before a fourth one finally seemed to work.

Two days later, during his second filtering session, Withey clogged another five filters. According to Quadrant, if a filter became clogged, it was because it captured a large quantity of circulating tumor cells and other pathogens. But there was another possible explanation the company didn’t discuss: Blood could coagulate inside the filter if the dialysis machine’s flow rate was set too low. Videos taken by Kim Hudlow during her husband’s first round of treatments showed the flow rate set at 80 milliliters per minute, less than half of what ExThera considered the optimal range.

Baskin became worried, because whenever a filter got clogged, the nurses would just throw it away with Withey’s blood inside. Including the blood in the connecting tubes, 335 milliliters of blood were being discarded each time. After five filter changes that day, Withey had lost nearly one-third of his blood.

When Withey was finally disconnected from his sixth filter around midnight, he looked white as a sheet. He stood up and walked over to his wife but then slumped to the floor unconscious and began shaking. Baskin became hysterical. A nurse rushed in and spent 10 minutes trying to resuscitate Withey before a doctor arrived and transferred him to the ICU.

The next day, John called Baskin from Miami and told her it looked like her husband had come down with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, a condition where platelets in the blood become dangerously low. Baskin was dubious because she knew HIT was a rare condition, and she suspected the real problem was simpler: Her husband had lost too much blood. But John assured her that Withey’s blood loss was manageable. When lab tests later showed her husband’s platelets rebounding — indicating that HIT was not the culprit — John agreed to order a blood transfusion.

While Withey recovered in the ICU, John Bowen had his third filtering session. His wife looked on anxiously as his blood pressure kept dropping. She said that she called John, the doctor, who assured her that everything was under control.

But Stacey Bowen was beginning to panic. When the filtering session was over and the nurse pulled the dialysis catheter out of her husband’s groin, he wouldn’t stop bleeding. Bowen frantically tried to reach Quadrant’s Pontzius, but he was on a flight to Asia. Another doctor on call eventually determined that John Bowen, too, needed a blood transfusion.

Citing patient confidentiality, John said he couldn’t comment on Hudlow’s, Withey’s and Bowen’s cases. “I am confident in the high quality of care provided at the clinic,” he said.

In a statement, Pontzius said that John is “a respected U.S. board-certified surgeon with more than 30 years of medical experience” and that he leads “a safe and thriving clinic.”

Pontzius said that many of the issues raised by the Times were “not factually accurate,” but he, too, declined to address specific patient cases.

David Hudlow’s Final Hours

The jet carrying the Hudlows touched down on a private landing strip in Jacksonville around 2 a.m. on April 10. Kim Hudlow rented a car near the airport and rushed her husband to the Mayo Clinic’s Florida campus. She knew that if she wheeled him into the emergency room, the hospital wouldn’t be able to turn him away. She was right. Mayo admitted him within five minutes of their arrival.

As she had suspected, David Hudlow suffered from pleural effusions. Doctors drained the fluid from his lungs, which helped him breathe. The bad news was that tumors in his liver, adrenal glands, bones and soft tissue had multiplied and grown. Other than offering hospice care, there was nothing the Mayo doctors could do. On April 16, Kim Hudlow drove him home to Panama City so he could spend his final hours with his family. He died two days later.

Kim Hudlow announced her husband’s death on a Facebook group she had created to share information about the filter treatments. In her post, she wrote that she didn’t blame the treatments for David Hudlow’s death and that she remained hopeful that “there may be some magic there.”

Looking back, though, she thinks the treatments accelerated his cancer’s progression. She says the ordeal also unnecessarily worsened the end of his life. Instead of putting him through exhausting travel and ineffective filtering sessions that increased his pain, she says, she could have provided him palliative care at home and kept him comfortable.

The Bowens flew back to Chicago from Antigua on April 15. John Bowen vomited on the plane. The next morning, Stacey Bowen rushed him to Northwestern Memorial Hospital. Doctors there found a clot in the same vein in which John had placed the dialysis catheter. They also diagnosed John Bowen with tumor lysis syndrome, a condition in which cancer cells fall apart and flood the bloodstream with chemicals and toxins faster than the body can get rid of them.

Upon seeing John Bowen’s blood work, one of the Northwestern Memorial doctors predicted he wouldn’t survive more than 48 hours. In the end, he lasted a week. He died on April 24, six days after David Hudlow.

Stacey Bowen said she and her husband had hoped the filter treatments would “be the miracle that would give him more time.” That did not happen.

“I’m angry,” she said. “They preyed on our desperation.”

Lab tests initially suggested that the cancer of Withey, the lone survivor among the three husbands, regressed slightly in the first few weeks after returning from Antigua. But his tumor cell counts soon soared to as much as five times their levels before the trip. Scans also showed growth in the tumors in his liver. He went back on high-dose chemotherapy.

Like Kim Hudlow and Stacey Bowden, Jaime Baskin believes that the filter treatment supercharged her husband’s cancer. That may be in part because it led him to stop undergoing chemotherapy, but it is impossible to know for sure.

Pontzius said Quadrant “has no reason to believe that the therapy had a negative impact on any patient’s health” and pointed out that many of the patients Quadrant treated “were terminally ill and had exhausted other treatment options.”

Quasha said the perceptions of grieving family members “are simply not reliable when compared to sound medical review and judgment of their care.” He encouraged the Times to ask Rosenberg, the oncologist who consulted on both Hudlow’s and Bowen’s care, for his clinical perspective.

Rosenberg said that Kim Hudlow and Stacey Bowen may be right to think that the filter treatments accelerated their husbands’ cancers — and therefore their deaths. “Did it cause hyper progression? I asked myself that,” he said. Rosenberg said it was possible that the blood filtering caused John Bowen’s tumor lysis by sparking “an overwhelming immune response,” though he said such a scenario would be “unusual.”

In addition to Hudlow and Bowen, the Times has learned of four other patients who died after their treatments in Antigua.

One of them was Kyle Chupp, who was diagnosed with metastatic abdominal cancer in December 2023. During a call the following month, Preston persuaded Chupp and his wife, Vanessa, to delay Chupp’s scheduled chemotherapy and radiation by telling them that the three patients who had fared the best in the Croatian study and were now cancer-free hadn’t had chemotherapy or radiation beforehand, Vanessa Chupp said. Kyle Chupp’s blood was filtered in Antigua in February. His health declined precipitously afterward, and he died on April 19.

Two of the other deaths involved patients that Preston had described as feeling remarkably better during his phone call with the Hudlows and Baskin, according to people with knowledge of the patients’ treatments.

One of them was Ashley Sullivan, who had metastatic breast cancer. Her husband, Edmund Mudge, said she did feel better after her first two filter treatments. But not long after the second treatment in March, she learned of a large new tumor between her ribs and lungs. Sullivan, 42, texted Ilic and asked her why the filter had worked so well for the Croatian patients but not for her, according to copies of the messages reviewed by the Times.

“Have NO idea who told you is not working for you,” Ilic texted back. “We got your CTCs down to zero.”

Three months later, Sullivan was dead.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

© 2025 The New York Times Company

Originally published on The New York Times