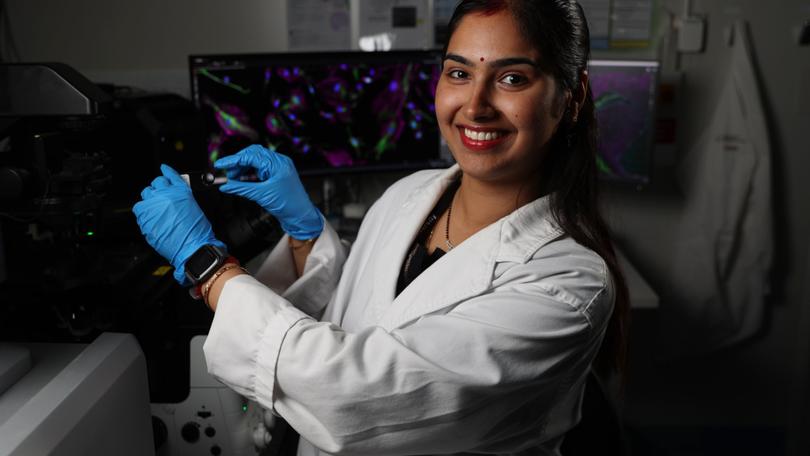

Fellowship winner to take on chameleon melanoma BRAF genes in fight against deadly skin cancer

It’s a question that’s stumped doctors for 20 years — why treatments suddenly stop working in half of melanoma patients. Medical researcher Sona Nayyar wants to find the answer.

Uncontrolled cell growth.

They are three words no patient wants to hear their doctor say during a post-medical test consultation.

The euphemistic words have been used for decades by medicos keen to avoid for as long as possible the coldest six letters in the English language: cancer.

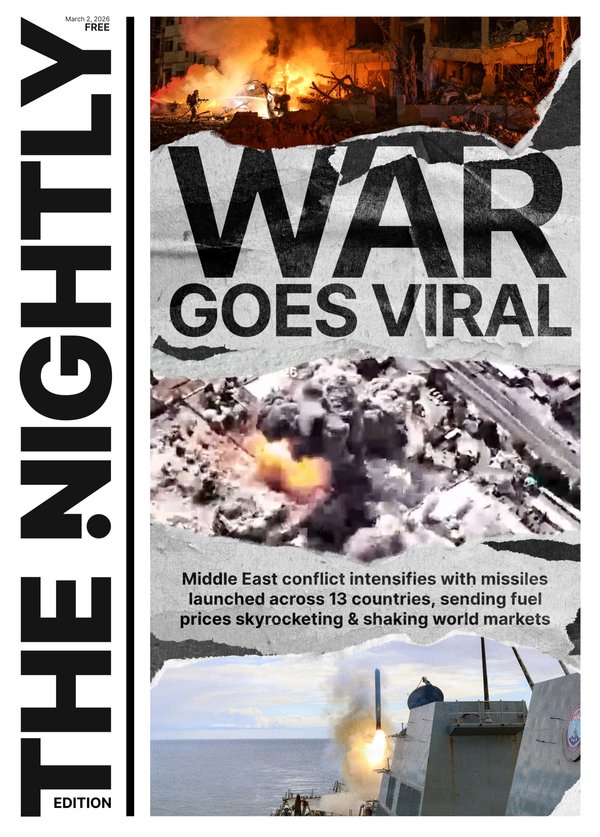

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Conversations which include the words uncontrolled cell growth or cancer often drift towards an explanation of the human body’s seventh chromosome.

The 160 million DNA building blocks that comprise chromosome seven spend their days regulating how quickly cells divide.

The BRAF gene, which is attached to this chromosome, plays a critical part in the process by instructing a protein that is central to the coordination of cell growth.

Skin cancer researchers have known for 20 years that the BRAF gene is mutated in half of all melanomas.

They successfully developed inhibitors which stalled the growth of cancer by binding to mutant BRAF genes and blocking their activity.

This treatment gave hope to the past generation of melanoma patients whose seventh chromosome was blighted by deviant BRAF.

It radically improved survival chances for a group of people who, up until then, had limited options and was hailed as one of the great advancements in cancer treatment.

But in a gut-wrenching development many recovering patients had the rug pulled from under them when the treatment inexplicably stopped working.

Scientists had underestimated a melanoma’s ability to adapt and evade conventional treatments.

The deadliest form of skin cancer has a canny knack for changing its characteristics in response to treatment, a dark skill known as cellular plasticity.

Researchers realised that the cancer’s unique ability to evolve this way limited the window for targeting the BRAF genetic aberration with inhibitors.

Medical researcher Sona Nayyar is devoting the next three-and-a-half years of her life to work out ways to out-flank these chameleon melanomas so current therapies have more time to work their magic.

Ms Nayyar’s work at WA’s Curtin University is being bankrolled by the Lions Cancer Institute, which has just awarded her a fellowship named in the honour of veteran Lions figures Colin Beauchamp and his wife Sue Goddard.

The PhD student will be overseen at the Curtin Health Innovation Research Institute by Pieter Eichhorn and Danielle Dye.

Curtin believes the new research project will see scientists delve deeper into the intricacies of melanoma biology with the goal of understanding how cancer cells are able to evolve following drug treatment.

“With this work we believe we will identify new cancer drivers which can be targeted therapeutically to prolong the quality of life for melanoma patients,” Dr Eichhorn and Dr Dye said.