THE WASHINGTON POST: Cosmologists intrigued by signs the universe might stop expanding

THE WASHINGTON POST: If an idea of ‘evolving dark energy’ holds up under further investigation, it would put many different cosmic futures in play.

The fate of the universe is still very much up in the air.

Right now it is expanding, at an accelerating rate. If nothing changes, many billions or trillions of years from now the universe would presumably become cold, dark and inhospitable.

But new data posted online Wednesday by scientists with the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) survey suggest this process of cosmic acceleration — attributed to a mysterious energy field dubbed “dark energy” — has been weakening over the past 4 billion to 5 billion years.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Dark energy may not be a “cosmological constant,” as generally assumed, but rather may evolve over time, according to the DESI scientists. If this idea of “evolving dark energy” holds up under further investigation, it would put many different cosmic futures in play.

Perhaps the universe will settle down into a serene maturity, never in a rush, imperturbable.

Or perhaps the acceleration will pick up again, as if someone turned a knob somewhere.

Or perhaps everything will go into reverse, and the whole business will contract again. That would be the ultimate turnaround - a cosmic 180.

“This result brings to the table, again, the possibility that the universe may not continue to expand forever. One of the possibilities now is that, in some theories, the universe could stop expanding, and re-contract into a Big Crunch,” said Mustapha Ishak, a cosmologist at the University of Texas at Dallas and co-chair of the working group that analyzed the data.

“We can’t foretell what dark energy will do in the future,” added Willem Elbers, a cosmologist at England’s Durham University and a co-chair of the working group.

Dark energy is the primary driver of cosmic evolution, but if that mysterious energy field decays, matter and gravity could become the dominant factors, he said.

“In that case, the ultimate fate hinges on a knife’s edge. Depending on how space is curved, a collapse is possible,” he added in an email.

For planning purposes, it is important to recognize that the timescale here is many billions or trillions of years. The DESI observations may be cosmically consequential but do not rise to the level of an action item for us mortals.

As observational data pours in, theoretical cosmologists have some work to do. There continues to be uncertainty about the Hubble Constant, the rate of the universe’s expansion, and whether there’s something glitchy in the estimates or, more profoundly, something wrong with the standard model for the evolution of the cosmos. Different estimates of the expansion rate have led to a decade-long debate dubbed the Hubble Tension.

New telescopes are coming online to try to discern what the universe is telling us about its past and future. NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope is under construction at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, and is on track for launch in two years.

Later this year, the Vera C. Rubin Telescope in Chile, funded by the National Science Foundation and the Department of Energy, is scheduled to begin observations. NASA’s SPHEREx space telescope, a relatively modest observatory, launched March 11. It will survey 450 million galaxies, testing theories that the embryonic universe underwent a period of exponential acceleration known as “cosmic inflation.”

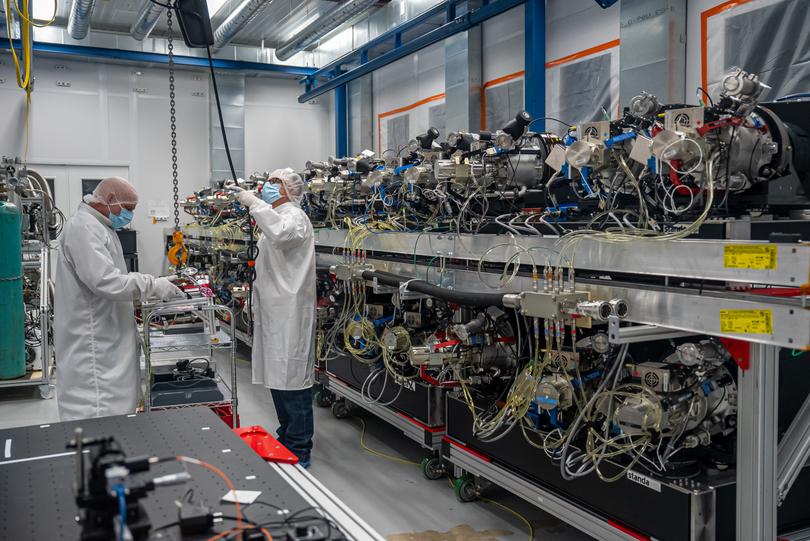

DESI, funded by the Department of Energy’s Office of Science and managed by the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, is an international collaboration involving 900 researchers and 70 institutions worldwide. The experiment uses a telescope at Kitt Peak in Arizona to map the history of the universe. Its dataset includes 13.1 million galaxies and 1.6 million quasars, which are very bright, distant objects powered by supermassive black holes.

So there’s a lot of data coming in, and the universe clearly hasn’t run out of ways to surprise cosmologists.

“I think the universe is giving us a lesson in cosmic humility. It doesn’t seem to be following the manual we had,” Adam Riess, a cosmologist at Johns Hopkins University who shared the Nobel Prize in physics for discovering the accelerated expansion of the universe, said in an email. Riess is not part of the team that published the new data.

“When a similar but slightly weaker version of this DESI result first appeared last year, many were not sure if this clue would sustain another year’s scrutiny and tripling of the data, but it has!” he said. “If confirmed, it literally says dark energy is not what most everyone thought, a static source of energy, but perhaps something even more exotic.”

If the DESI news sounds vaguely familiar, it is because last April the same team announced a similar result. The difference is the quantity of the data — more than twice as many galaxies studied — and the confidence in the result.

The team is still not claiming a “discovery,” but the probability that the results will hold up with further study is increasing. Although the new data has been posted online, it has not yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal.

“We are still at the ‘interesting’ or ‘stay tuned’ level. Very intriguing but not yet definitive,” cosmologist Wendy Freedman of the University of Chicago, who is not part of the DESI team, said in an email.

On Tuesday, another team of scientists, the Atacama Cosmology Telescope collaboration, posted online the results of observations of the most ancient light in the universe - the cosmic microwave background radiation. In a news release, the team described the data as “the clearest and most precise images yet of the universe’s infancy.” The radiation was emitted 380,000 years after the Big Bang, when the expanding universe first became transparent to light.

Jo Dunkley, a Princeton astrophysicist, said in an email that the new data supports the standard model in cosmology, called Lambda Cold Dark Matter. It does not rule out the possibility of evolving dark energy as suggested by the DESI results so far, she said.

“I think that until we figure out what dark energy is, almost anything is in play - i.e. the dark energy could change its behavior in the future in a way that leads to a Big Crunch, even though that’s not what the simpler models would suggest,” she said.

© 2025 , The Washington Post