ROSS CLARK: Why the West’s plunging birthrate could usher in a terrifying dystopia

The West’s falling birthrate could usher in a terrifying dystopia where cities are abandoned and a small numbers of residents cling to decaying houses set on empty, weed-strewn streets.

Picture the cities of the future. Do you imagine glittering skyscrapers, bullet trains whizzing past green parklands, flying taxis and limitless clean energy?

I’m afraid you may be disappointed.

A century from now, swathes of the world’s cities are more likely to be abandoned, with small numbers of residents clinging to decaying houses set on empty, weed-strewn streets – like modern-day Detroit.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.According to a new report from the Lancet medical journal, by the year 2100, just six countries could be having children at “replacement rate” – that is, with enough births to keep their populations stable, let alone growing.

All six nations will be in sub-Saharan Africa.

In Europe and across the West and Asia, the birth rate will have collapsed – and the total global population will be plummeting.

Eco-activists have long decried humans as a curse on the planet, greedily gobbling up resources and despoiling the natural world.

The reliably hysterical BBC presenter Chris Packham has claimed that “human population growth” is “our greatest worry… there are just too many of us. Because if you run out of resources, it doesn’t matter how well you’re coping: if you’re starving and thirsty, you’ll die.”

Greens like Packham seem to think that if we could only reduce the overall population, the surviving rump of humanity could somehow live in closer harmony with nature.

On the contrary, population collapse will presage a terrifying dystopia.

Fewer babies mean older populations – which in turn means fewer young people paying taxes to fund the pensions of the elderly.

And that means that everyone has to work ever longer into old age, and in an atmosphere of declining public services and deteriorating quality of life.

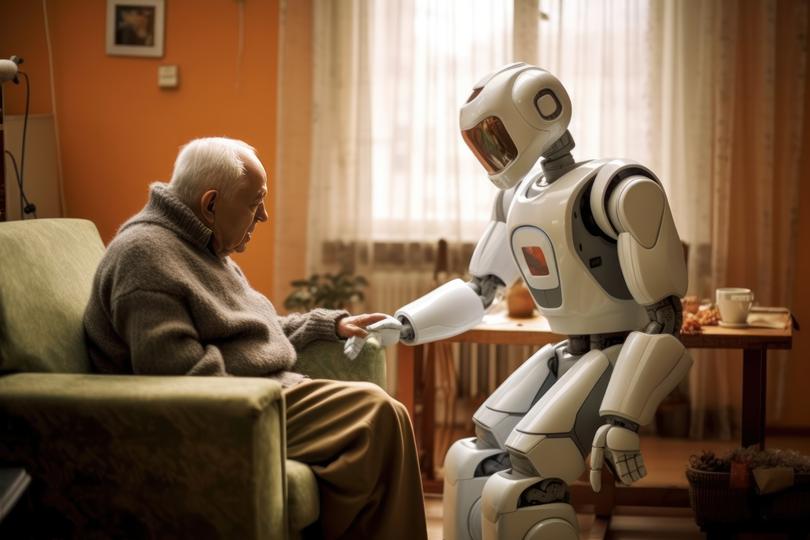

So if you worry that it’s hard now to find carers to look after elderly relatives, this will be nothing compared to what your children or grandchildren will face when they are old.

In modern industrialised societies, it is generally accepted that the Total Fertility Rate (TFR) – the average number of children born to each woman during her lifetime – must be at least 2.1 to ensure a stable population.

By 2021, the TFR had fallen below 2.1 in more than half the world’s countries.

So what, if anything, can we do to stop ourselves hurtling towards this calamity?

In Britain, it now stands at 1.49. In Australia it is 1.63, in Spain and Japan it is 1.26, in Italy 1.21 and in South Korea a desperate 0.82. even in India – which recently overtook China as the world’s most populous nation – the TFR is down to 1.91.

There are now just 94 countries in which the rate exceeds 2.1 – and 44 of them are in sub-Saharan Africa, which suffers far higher rates of infant mortality.

The dramatic fall in Britain’s birthrate has been disguised until now because we are importing hundreds of thousands of migrants per year to do badly paid jobs that the native population increasingly spurns.

In 2022, net migration there reached more than 700,000.

The Office for National Statistics expects the UK population to reach 70 million by 2026, almost 74 million by 2036 and almost 77 million by 2046 – largely fed by mass migration.

Unless migration remains high, the UK population is likely to start shrinking soon after that point – especially as the last “baby boomer” (born between 1946 and 1964) reaches their 80th birthday in 2044.

This mass importation of migrants to counteract a falling domestic birthrate spells huge consequences for our social fabric.

In years to come, Britain is set to face a pitiless battle with other advanced economies – many of them already much richer than we are – to import millions of overseas workers to staff our hospitals, care homes, factories and everything else.

And once the global population starts to fall in the final decades of this century, it will become ever harder to source such workers from abroad.

At that point, we may find hospitals having to cut their services or even close.

So, though medical advancements will likely mean that people will be living even longer, we face a grim future in which elderly people will increasingly die of neglect, or be looked after by robots – an idea that has been trialled in Japan already.

How has this crisis crept up on us so stealthily?

It wasn’t so long ago that the United Nations and others were voicing concern at overpopulation. For decades, self-proclaimed experts have warned – in the man manner of early 19th-century economist Thomas Malthus – that global supplies of food and water, as well as natural resources, would run out.

Graphs confidently showed the world’s population accelerating exponentially, with many claiming that humankind had no choice but to launch interplanetary civilisations as we inevitably outgrew our world.

They could not have been more wrong.

Amid all the Packham-esque hysteria about a “population explosion”, many failed to notice that birth rates had actually already started to collapse: first in a few developed countries, such as Italy and South Korea, and then elsewhere.

On current trends, the world’s population will start to fall by the 2090s – the first time this will have happened since the Black Death

As societies grow wealthier and the middle classes boom, women start to put off childbearing.

This means that they end up having fewer children overall.

In Britain especially, there are the added costs of childcare and the often permanent loss of income that results from leaving the workforce, even temporarily.

The striking result of all this is that the number of babies being born around the world has, in fact, already peaked.

The year 2016 is likely to go down in history as the one in which more babies were born than any other: 142 million of them.

By 2021, the figure was 129 million – a fall of more than 9 per cent in just five years. To be clear, the global population is for the moment still rising because people are living longer thanks to better medical care.

We are not dying as quickly as babies are being born.

According to the UN, the global population reached 8 billion on November 15, 2022.

It should carry on growing before peaking at 10.4 billion in the 2080s – although the world will be feeling the effects of the declining birth rate long before that.

On current trends, the world’s population will start to fall by the 2090s – the first time this will have happened since the Black Death swept Eurasia in the 14th century.

So what, if anything, can we do to stop ourselves hurtling towards this calamity?

For one thing, governments must work tirelessly to encourage people to have families.

Generous tax incentives for marriage, lavish child benefit payments and better and cheaper childcare are all a must, so that mothers don’t have to stop their careers in order to start families.

Britain could, if it chose to, lead the way on this. But that seems highly unlikely with the imminent prospect of a Labour government: the statist Left habitually loathes any measures that could be seen to benefit the nuclear family or that incentivise people to have more children.

Yet in truth, the scale of this problem is so vast – and the issue so widespread – that effectively counteracting it may be next to impossible.

Absent some extraordinary shift, the gradual impoverishment of an ageing and shrinking population seems the planet’s destiny.

It is not an attractive thought.