Anzac Day disruptions across Australia highlight tensions over welcome-to-country ceremonies

AARON PATRICK: Protests against the Indigenous rituals at an Anzac Day Dawn Service were condemned by political leaders but drew support from some members of the public.

Anzac Day drew large crowds around the nation on Friday to celebrate the one-and-a-half million Australians who fought in wars from colonial South Africa to Afghanistan, but the disruption of Welcome-to-Country ceremonies at Melbourne’s Shrine of Remembrance and Perth’s Kings Park triggered a debate about whether the recognition of Indigenous Australians in public life had gone too far.

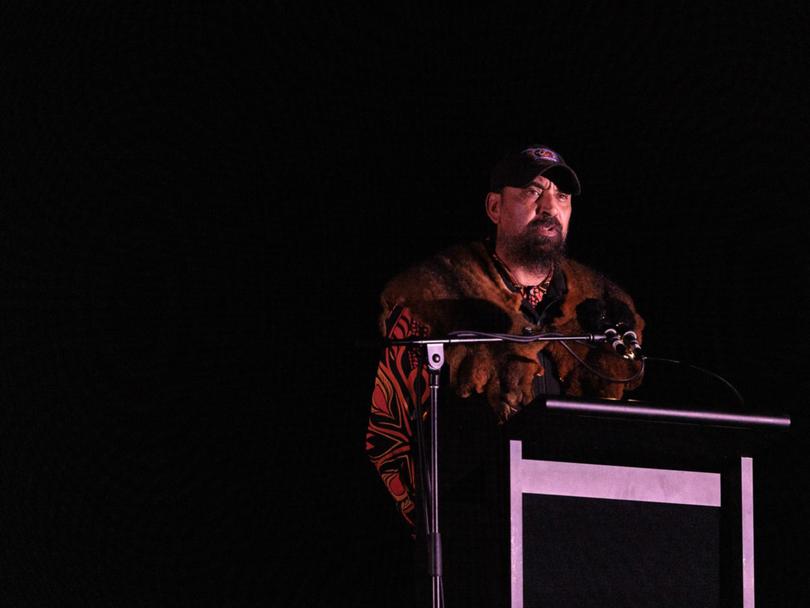

In Melbourne, people booed and heckled as Aboriginal representative Mark Brown gave a speech before dawn about the importance of cultural diversity. “What about the Anzacs?” one said. “We’re here for the Australians,” another called out.

Victorian Governor Margaret Gardner was also booed when she acknowledged the pre-European landowners. One person yelled, “give us our country back,” and another said, “we don’t have to be welcomed”.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Witnesses identified the protest leader as 26-year-old Jacob Hersant, the first man convicted in Victoria of performing a nazi salute under a law introduced in 2022. He was led away by police officers and was expected to be charged with offensive behaviour.

Political leaders from the major parties immediately condemned the protests, led by Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, who described them an act of cowardice.

“The disruption of Anzac Day is beyond contempt, and the people responsible must face the full force of the law,” he said.

Liberal leader Peter Dutton, who attended his local service in Samford, on the Brisbane outskirts, said: “To see any instance, whatsoever, of neo-nazis in our country is just a disgrace.”

Protest supporters

Online, a video clip of the Melbourne incident attracted more than 3300 comments, many supportive of the protests, including some from people who identified themselves as military veterans.

“Anzac Day is not the time and definitely (not) a service to have welcome to the country,” Estelle McBride wrote on Facebook.

“We are all here and free because of our soldiers, no matter what heritage we have.”

Ben McKewin wrote under the same clip: “Imagine being a veteran and having to be welcomed into his own country that he fought for.”

Victorian Labor Premier Jacinta Allan said the booing was “beyond disrespectful”.

“Anzac Day honours the values our Anzacs lived and died for: courage, loyalty, mateship, and sacrifice,” she said.

“Those who booed in the dark showed they have none of these qualities.”

A One Nation MP, Sarah Game, criticised the booing, but said it was disappointing the Indigenous ceremonies were “so staunchly defended by various politicians”.

In Perth, a man called out racist comments while the president of an Indigenous veterans charity, Di Ryder, performed a Welcome-to-Country ceremony. Others in the crowd told him to “shut up”. At the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, 25,000 people attended a dawn ceremony that was disrupted by a person who called out “free Palestine” after the traditional minute’s silence. Someone else said: “Kick a landmine.”

Welcome not required

Many ceremonies mentioned the estimated 5000 Aboriginal men and women who served in the military in World War I and II, even though they faced racism at home.

The Returned and Services League of Australia, known as the RSL, directs Anzac Day organisers to conduct an “Acknowledgement of Country” but does not require the longer Welcome-to-Country ceremonies, a modern version of the tradition of Aboriginal tribes giving permission for others to pass through their territory.

The ceremonies became common at public events over the past decades as Australians became more aware of the plight of Aboriginal people, who are generally poorer, less healthy and die younger than other Australians.

As the ceremonies spread, resentment built in some areas against what was seen as an attempt to make people feel guilty for their mistreatment by previous generations. In December, rugby league club Melbourne Storm said it would reduce the number of welcome-to-ceremonies before games.

In parks and monuments around the country, hundreds of ceremonies were held to commemorate the 110-year anniversary of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps landing on the Gallipoli Peninsula in what is now Türkiye, in a failed attempt to knock the Ottoman Empire out of World War I.

Governor-General Sam Mostyn attended a service at the beaches where they stormed ashore in 1914. She described wading into the water with her husband and military aide.

“As hard as we tried, it was impossible for us to put ourselves in the boots of those soldiers,” she said. “Where we found peace, they encountered the fury and the maelstrom of bullets and shrapnel.”