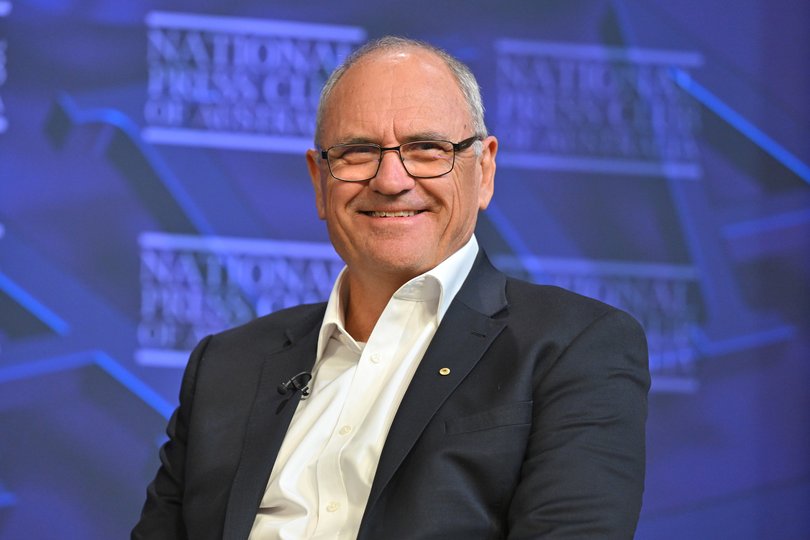

JACKSON HEWETT: Ken Henry reveals why the average full-time worker is $500k worse off

The former head of Treasury has laid bare the problems with Australia’s productivity

One of Australia’s top policy minds has blown the lid on a future that is heading toward higher taxes and a lower standard of living.

Ken Henry, who served as Treasury Secretary from 2001 to 2010 under both Liberal and Labor governments, has laid bare the impact of failing to deal with the country’s plummeting productivity.

It was an issue he identified almost a quarter of century ago in the 2002 Intergenerational Report, and lamented that his very conservative estimate for Australia productivity was way off.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.At the time, Treasury used a long-run average of 1.75 per cent annual productivity growth — itself lower than the 2.25 per cent achieved during the 1990s.

That 1.75 per cent was closer to the long run average before the Hawke-Keating reforms, and even then it would not be enough to sufficiently grow the economy to account for the growth in spending. Even with that 1.75 per cent baseline, Treasury forecast taxes would need to rise by five percentage points of GDP to cover rising spending. If the country could repeat the productivity performance of the 1990s for 40 years, that tax burden could be avoided.

Instead, productivity growth came in well below expectations.

“We didn’t achieve the one and three-quarters,” Mr Henry said. “We certainly didn’t achieve the two and a quarter. What we’ve achieved is closer to three-quarters of a per cent a year.”

And this is where the rubber hits the road. Productivity is critical for wage growth, without growth in productivity the Reserve Bank has to keep interest rates unnecessarily high in order to ensure wages rises don’t cause inflation.

“Assuming real wages grow pretty much in line with productivity growth — how much has this cost the average Australian worker?” Dr Henry asked a gathering at the National Press Club.

“I came up with a remarkable number. It has cost the average full-time worker more than half a million dollars over the past 25 years.”

Ahead of the Government’s upcoming productivity roundtable, the architect of the Henry Tax Reforms, which in the main have never been introduced, continues to push the public debate.

And call out special interests for delaying much needed reforms.

“When I hear people say, ‘Oh, we can’t do this to enhance productivity, we can’t do that because it might hurt somebody’ — I think, give me a break.

“Who are we talking about here?”

Not the average worker, and certainly not young people.

In a speech earlier this year, Dr Henry argued young Australians are being systematically punished by a tax system designed to protect older, wealthier cohorts — and said that no government since the Rudd era had upheld the fiscal principles set in the Charter of Budget Honesty to ensure fairness between generations.

Instead, governments of all stripes have taken the easy way out, relying on bracket creep to draw more deeply on workers’ incomes.

“Young workers are being robbed by a tax system that relies increasingly upon fiscal drag,” he told a tax summit. “Fiscal drag forces them to pay higher and higher average tax rates, even if their real incomes are falling.”

Dr Henry described the ongoing failure to address expanding tax burden, along with the lack of affordability in housing, rising costs of higher education and the dangers of climate change as “reckless indifference” at best but likely something more sinister.

”Wilful acts of bastardry, more likely,” he then said.

Dr Henry told the tax forum that the “structure of our tax system offends intergenerational equity” and a recent report by the Tax and Transfer Institute at the Crawford School at ANU confirms it.

The paper finds that Australia’s tax and transfer system has become increasingly generous to older Australians over recent decades, both through rising public spending and favourable tax treatment, while support for younger households has remained flat. Crucially, this is not just a function of an ageing population; the authors measured spending per capita.

Government spending on age-based supports, including the age pension, aged care and health care, has increased significantly in real terms for older Australians.

At the same time, older Australians have enjoyed growing private income, especially from lightly or untaxed real estate and superannuation, which younger cohorts have not had access to at comparable life stages.

The result is a dramatic shift in the balance of who benefits most from Australia’s tax and transfer system. In the 1990s, Australians over 60 had private income equal to just 41 per cent of that earned by people aged 18 to 60, and final income (after taxes and transfers) that was 61 per cent of the younger group.

Today, that gap has almost closed or flipped entirely. Over the past decade, Australians over 60 earned 65 per cent of the private income of working-age Australians, but after accounting for tax breaks were effectively at par, achieving 95 per cent of under 60s’ after-tax income.

The contrast is even sharper when compared with young adults. Australians aged over 60 now earn 11 per cent more than those aged 18 to 30, and after tax and transfers, they enjoy incomes that are 60 per cent higher.

“To achieve a fiscally sustainable budget over the coming decades, Australia must choose between increasing taxes and reducing government expenses,” the report argues.

“The consequences ... should be borne, at least in part, by older Australians. Achieving budget sustainability solely by increasing taxes on Australians of working age (mostly by growing personal income tax revenue through bracket creep) will worsen generational imbalance.”

Even the Commonwealth Bank recognises the issue. In its submission ahead of the Productivity Roundtable, it warns “the next generation may be the first in modern history in Australia to be financially worse off than their parents.”

To avoid that outcome, the bank calls for a coordinated national productivity agenda, anchored in tax reform, investment incentives, and a policy environment that supports innovation and business dynamism.

It draws particular attention to Australia’s heavy reliance on personal income tax compared to other OECD countries, warning that this not only reduces incentives to work and upskill, but also disproportionately affects younger and middle-income earners. Unlike business lobby groups, it doesn’t call for company tax rates to be cut.

Without reform, the bank warns, Australia risks entering a prolonged period of economic stagnation, declining social mobility, and a breakdown in the generational bargain.

Commbank called for reforms that relieve “cost of living and affordability pressures”, including “an abundance of low cost, reliable, low emissions energy, (and) an abundance of affordable housing.”

Dr Henry, now chair of the Australian Climate and Biodiversity Foundation, agrees with that assessment and used his address to the National Press Club to call out the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act for failing to do any of that. He called out the 38 reforms suggested by Graeme Samuel that had not been acted on.

“(They could) change the trajectory of nature loss and to ease the burden of the complexity, confusion and meaningless process. It’s been a cause of frustration to land holders and the business community and which has undermined national productivity,” he said.

He said the Act was holding back the building of greenfield homes, the mining of critical minerals, and the construction of renewable energy. Of the 124 renewable projects submitted to the EPBC, only 28 had been either approved or rejected he said.

With layers of State and Federal regulation, the act is a dead weight on projects “critical to enhancing economic resilience and lifting Australia’s flagging productivity growth.”

Dr Henry is in no way a no-growth hippy, but he does recognise that it must occur with in the earth’s boundaries or the intergenerational inequity would be far worse.

“Lifting productivity growth is going to require much better articulation of the natural constraints affecting the choices available to us. These must be written into law in the form of enforceable national environmental standards in reforming the EPBC Act,” he said.