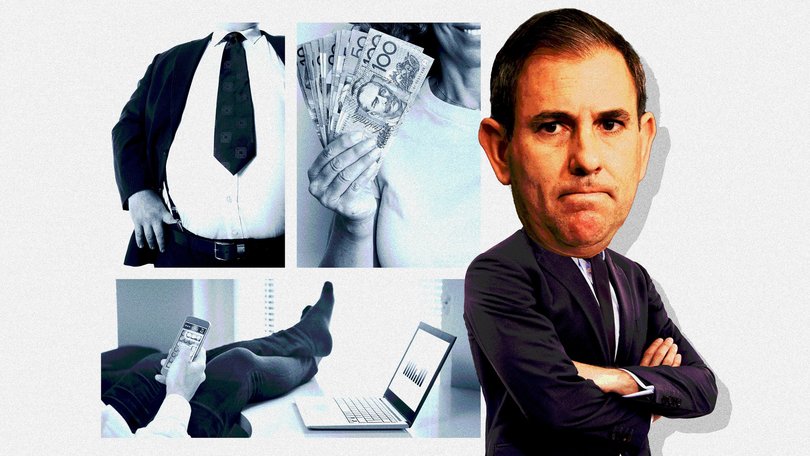

AARON PATRICK: When it comes to economic progress, Australia has become rich, fat and lazy

AARON PATRICK: When it comes to economic progress, Australia is lagging. It’s time for Jim Chalmers to cut red tape, speed up projects and build more homes.

Economist Chris Richardson has scored one of the most coveted invitations going in Canberra, to the government’s policy “roundtable” in two weeks.

The tax and budget expert knows the three-day event won’t be short of ideas to reverse Australia’s poor economic growth record. He’s worried it may lack something just as important, and intangible: leadership capable of convincing the big egos and powerful interests that will gather around the cabinet table (which is oval, not round) to compromise on their positions.

“How do you get a bunch of people to agree on stuff when they really don’t want to?” he asked The Nightly. “The politics of ‘no’ has never been more successful here and around the world.”

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Mr Richardson’s concerns about ego and self interest raise important questions about management of the event. Will Jim Chalmers emerge as a genuine negotiator? Does the treasurer want to? Is there anyone else with the authority or moral courage to put aside their biases and bring about agreement for the nation’s sake?

The argument for action is so compelling it is worth repeating. When it comes to economic progress, Australia has become rich, fat and lazy. The average Australian’s living standards rose by 1.5 per cent over the past decade. Across the rich world as a whole, they rose 22 per cent.

Getting better

The reasons are complex and contested. The problem is not. Except for a few fringe or idiosyncratic commentators, there is agreement workers’ productivity should improve so wages can rise. Which just means Australia has to get better at making and doing stuff.

Baked into the economy, inefficiency is terribly hard to stamp out. Often it is introduced as well-intentioned rules to protect people and the environment that morphs into unnecessary edicts. One example is a requirement for tug boat crews to be fully staffed even when they aren’t needed.

Other times inefficiency happens when influential groups secure special advantages for themselves. Thanks to the construction union, for example, traffic controllers on large building sites can earn $200,000 a year.

Business groups would like to stamp these costs out. Unions would like business and the wealthy to pay more tax. The debate over workplace efficiency is so fraught that it would be remarkable if it was seriously discussed at the Canberra gathering.

Similarly, many experts, including Mr Richardson, would like the tax system changed.

A popular idea is to raise and extend the GST in return for income tax cuts. This would capture more money from criminals, who generally dodge income tax. But the GST is seen, politically, as being associated with the Liberal Party. Raising it might upset Labor voters.

Playing it safe

Rather, Dr Chalmers is expected to play it safe. People closely following developments think he will steer the discussions towards reducing business regulation; speeding up approvals of new factories, mines and other large industrial projects; and changing building codes to make it easier to construct houses and apartments.

For a politician who prides himself on being a great communicator, the options are easy to summarise in a three-phrase sentence almost no reasonable person would challenge: cutting red tape, speeding up projects and building more homes.

Apart from making a clear slogan, such promises would have the advantage, for the Government, of being vague, difficult to measure, and carry responsibilities shared with the states. The moment when the Government would be held accountable might never come. In other words, they would be promises with little political risk.

Which may help explain why the Prime Minister, who proposed the meeting in the first place, seemed to lower expectations of policy breakthroughs this week. On Thursday, asked about a union suggestion to reduce tax breaks for property investors, he sounded like a leader dismissing a suggestion he has heard many times before.

“The only tax policy we’re implementing is the one we took to the election,” Mr Albanese told reporters in Melbourne.

The prime minister was presumably referring to a plan to increase taxes on superannuation accounts with more than $3 million and a small cut in personal income taxes.

A golden ticket

Demand for slots at the meeting has been strong. When Mr Richardson, the economist, got his invitation to the third day, which will discuss tax and the federal budget, he posted an image online of a golden ticket to Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory.

As one of the few truly independent attendees, Mr Richardson sounded nervous about his ability to help convince others to compromise. “Say a little prayer for me,” he posted on LinkedIn.

He’s also conscious the political environment is hostile to policies, that no matter how good for the nation, will hurt some interests.

“We have already seen some stakeholders say no to some things,” he told The Nightly. “So its no surprise that the politicians are dialling expectations back down. I get that. But how is Australia going to change? Because we need to change.”