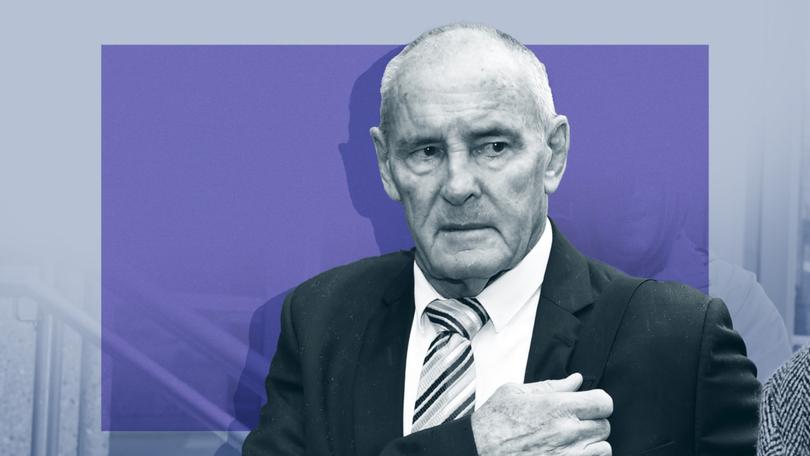

Christopher Dawson got away with murder for decades, now he’s likely to die in jail for killing his wife

Former rugby league star Christopher Dawson is likely to die in jail after NSW highest criminal court rejected his appeal for the murder of his wife Lynette

The downfall of former rugby league star, murderer and sex-pest teacher Christopher Dawson is all but complete, with a court overturning his appeal and leaving him with the prospect of dying in jail unless he takes his battle for freedom to the High Court.

In a NSW Supreme Court judgment handed down on Thursday afternoon by the Court of Criminal Appeal, Justices Julie Ward, Anthony Payne and Christine Adamson unanimously dismissed 75-year-old Dawson’s appeal against his conviction for killing his wife Lynette Simms on the grounds of a miscarriage of justice.

The judgment is the latest chapter in an extraordinary saga that was sparked in 2018 by a hit podcast The Teacher’s Pet from investigative journalist Hedley Thomas.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.It told the story of man who had literally gotten away with murder, the charismatic Dawson who was living freely in Queensland decades after the disappearance of his wife Lyn.

A former star football player with the Newtown Jets, Dawson had moved his teenage lover and babysitter for his two young daughters into the family home in the days after his wife disappeared in January 1982.

Dawson’s “obsession” with his 17-year-old lover, named JC in court, whom he had taught at a Northern Beaches school and who had been vulnerable due to her chaotic home life, had driven him to kill his then 33-year-old wife, said the judgment.

“The evidence about the nature of the applicant’s relationship with JC showed a degree of desperation and obsession on the part of the applicant,” the judges said.

“The applicant was controlling of JC, who was a teenager. The applicant was prepared to take increasing risks to preserve his relationship with JC in the face of her increasing resistance.

“The applicant was the last person to see the deceased alive and had a strong motive and opportunity to kill her. Shortly put, I am persuaded beyond reasonable doubt of the applicant’s guilt.”

But even with the weight of justice delivered to Dawson, 77, the family and friends of Ms Simms — including her now grown daughters — have still not been able to bury her properly, with her killer refusing to shed light on the whereabouts of her body.

This callousness sparked a change in legislation, with Lyn’s Law passed by the NSW Parliament to stop killers from getting parole if they don’t reveal where they buried their victims.

When found guilty in 2022, Dawson was sentenced to 24 years in prison with an 18-year non-parole period and was told that he will likely die in jail.

With no body and deficiencies in the initial police investigation, the Dawson prosecution was entirely circumstantial and relied heavily on the fact that Ms Simms — who the judges referred to by her married name — would never have left behind family members who she was close to.

Having had trouble conceiving her two- and four-year-old daughters and to whom she was a devoted mother, Ms Simms would also not have abandoned them.

Dawson initially told police and her family that he dropped his wife at a bus stop on the morning of January 9, 1982, before going to work at Northbridge Baths. He later invented phonecalls from her that he said proved she had deserted her family.

His murder trial heard evidence that in the months before Ms Simms disappeared he had tried to leave her for JC, something that he hid from police who investigated his wife’s disappearance.

“The applicant had shown himself to be entirely without credibility, both by reference to direct lies and half-truths, of which there is a litany in the evidence and his versions,” the judgment said.

“There is no possibility that Lynette Dawson voluntarily left her children on the morning of January 9 without speaking to members of her family, particularly her mother.

“Lynette Dawson would not have ceased her relationship or communication with her parents and siblings voluntarily. She would not have left her children, even for a few days, without telling her mother.”

And by moving his lover into the family home, Dawson had “conducted himself in a manner which was completely irreconcilable with any purported belief that the deceased might return to the marital home”.