Sextortion scourge claims four Victorian teens as cyber-safety expert Susan McLean issues grim warning

At least four Australian children, in Victoria alone, have recently committed suicide after being ‘sextorted’, according to a leading cyber-safety expert.

At least four Australian children, in Victoria alone, have recently committed suicide after being ‘sextorted’, according to a leading cyber-safety expert.

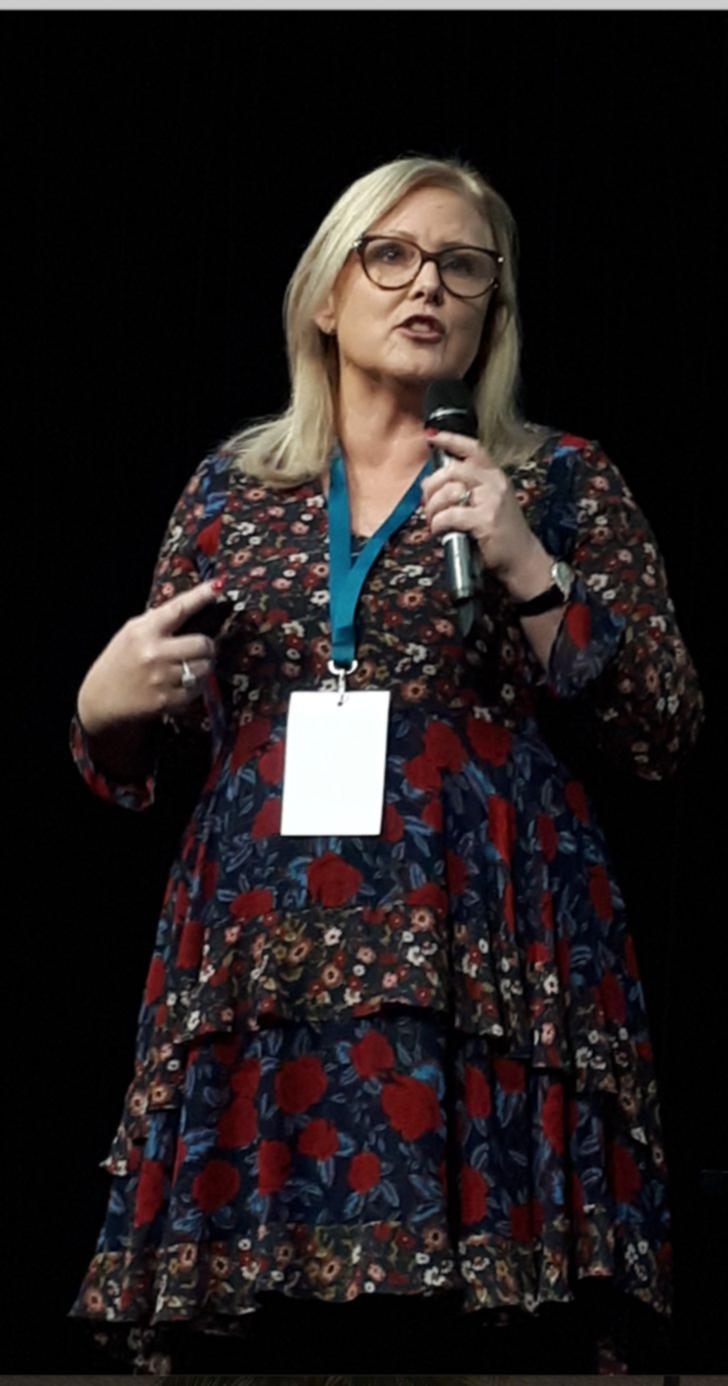

Former ‘cyber cop’ Susan McLean, who served in the Victoria Police Force for 27 years, said she knows of at least four youth suicides – involving three boys and one girl – that were linked to sextortion in the last two years.

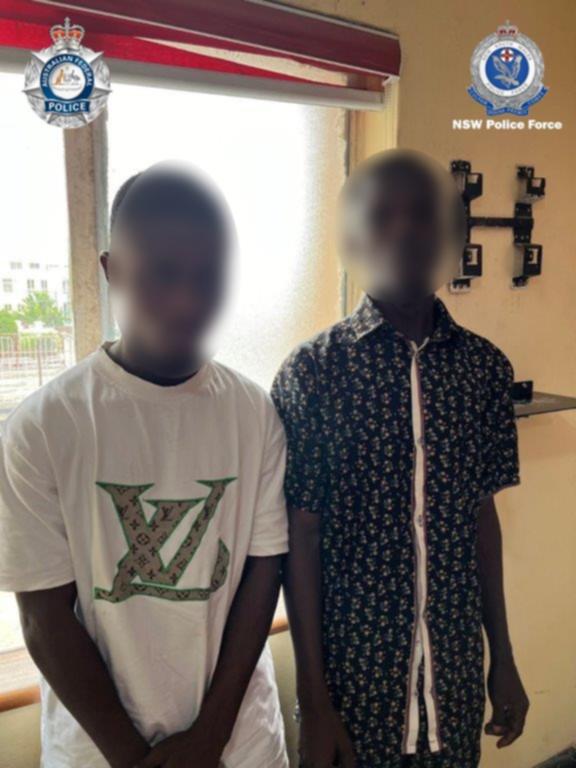

It comes after New South Wales Police this week revealed that a teenager had taken his own life late last year after being blackmailed by two men in Nigeria, who had threatened to disseminate his intimate images unless he paid them $500 in gift cards.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.“I’m personally aware of four teenagers who have died from suicide that have been linked back to sextortion … all in the last two years,” Ms McLean said.

“All that is new about this (NSW case) is that it hit the media and there was an arrest. It was the first one that was made public, and that’s the difference.

“It was only luck that the police decided, for whatever reason, to look in his phone.”

Sexual extortion is a form of online blackmail where someone tricks you into sending your sexual images and then threatens to share them unless their demands are met.

To entrap their victims, criminals set up fake social media accounts where they frequently pretend to be attractive young women on Instagram and Snapchat, and use tried and tested scripts.

Ms McLean said the crime itself has been around for at least 15 years, but the explosion of cases involving children was new.

“It’s not an emerging issue. I took my first report of sextortion in 2009 so it’s not a new crime,” she said.

“It’s been around a long time, but it’s really only been in the last two years that we’ve seen this explosion, where they’re targeting kids because they’ve worked out that kids are an easy target.

“These organised criminal gangs have worked out that instead of hitting up an adult for $5000, it’s easier to hit up a kid – or 200 kids – for $50 each.”

The author of “Sexts, Texts and Selfies” said that perpetrators were predominantly based overseas in West African countries such as Nigeria.

Usually they demand victims transfer money, or send them cryptocurrency, gift cards or online game credits.

“It’s very hard for a kid in Australia to send money to Nigeria so they demand iTunes gift cards and other gift cards which are basically electronic money,” she said.

“You can purchase it and send it in an email, which is a very easy transaction for a kid to do rather than having to go and try to find a money transfer place.

“We also know that when girls are the victims, (the criminals) will often ask for more photos instead of money.”

When targeting boys, the demand is usually for payment.

“Most teenage boys happily and willingly share dick pics and (offenders) know that they will come up with some money,” she said.

“I know teenagers who have paid $5000 because they’ve had part-time jobs and they’ve thought that it would fix the problem which of course, it doesn’t.”

Ms McLean, director of Cyber Safety Solutions, said victim “suicides are not new either” and the risk of self-harm among young people ensnared in sextortion was “very very high”.

“I’ve never seen a crime type in 30 years that will tip a mentally-well young person into crisis so quickly,” she said.

“It is the shame; humiliation and the messages (victims) will get from these people are hideous.

“They will say things like ‘I will ruin your life, I have ruined your life, you will never recover from this, your parents will hate you, how much can you pay before you’ll kill yourself?’

“Victims are fed all of these horrible messages which in general are not nice but when they’re targeted at you, and you know you’ve stuffed up, (we see) mentally-well teens with no issues suddenly take their own life.”

The author and educator said that, in her experience, offenders primarily target kids on social media before moving the conversation to a different platform.

She said SnapChat was by far the worst social media platform for sextortion.

“I think there is a perception (with SnapChat) that it can’t be traced and things like that but it can happen on any app that allows communication,” she said.

“Normally they find them on one platform and move them onto another.

“Kick is another one they use.”

While social media companies can and should do more to keep young people safe online, Ms McLean said educating kids and parents is “our best option”.

“We need to encourage kids to disengage (with offenders) and tell someone straight away,” she said.

Her strong advice to parents who become aware of their child being blackmailed is to shelve fear and judgement.

“If you become aware this has happened to your child, the first five steps are mental health support,” she said.

“If that means going to the Emergency Department, the GP, sleeping on the floor next to their bed at night, that’s what you have to do.

“Make sure they know they are not in any trouble; they haven’t done anything wrong and they’re the victim of someone else’s criminal act. And that it can be fixed.”

If your child is under 18, report it to The Australian Centre to Counter Child Exploitation, which is run by the Australian Federal Police and has a dedicated portal for reporting such crimes.

If your child is over 18 and their intimate images or videos have been shared, report it to the e-Safety Commissioner, who can have the material taken down.

Ms McLean said it was impossible to grasp the scale of the “underreported crime” because data about the causes of youth suicide is rarely recorded.

She said it was not, but should be, “standard practice” for police to search the phones of youth suicide victims to determine whether online abuse had pushed them to end their life.

“My argument to Victorian Coroner for the last five years has been that every time there is a youth suicide, you should look into his phone and their social media to see if we can find a pattern of anything,” she said.

“Personally I believe it should be mandatory and written into police procedural manuals that if a young person, up to 18 or 20 years old, commits suicide, their phone needs to be checked, as does their social media.

“It might show nothing but it might show they’ve been sextorted. Unless we do this next step, we won’t know (if sextortion was involved).

“For everyone’s benefit, you need to find out the causal factors for suicide if you can.”

If you’re in crisis, call Lifeline on 13 11 14 or Kids Helpline on 1800 55 1800