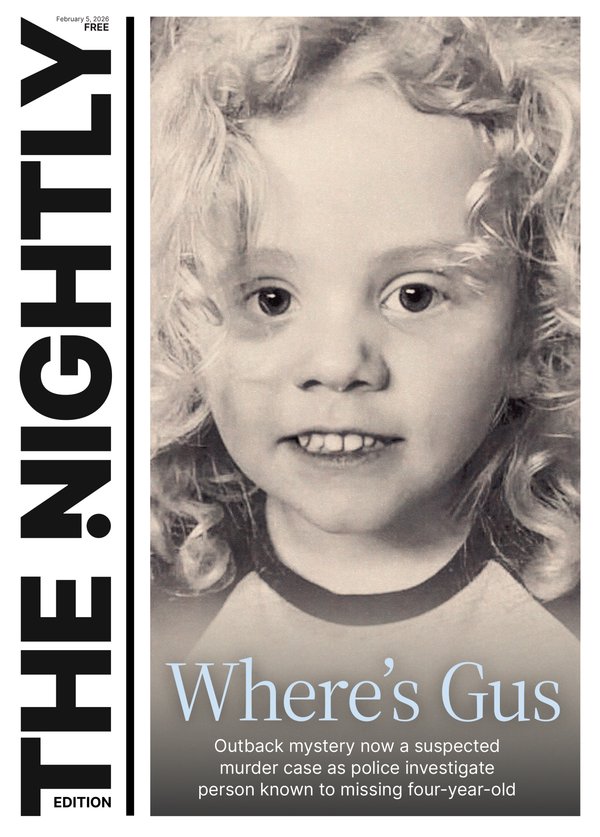

Kirsty Clarke: A mother’s mission to rescue kids from online child sexual abuse and lock up perpetrators

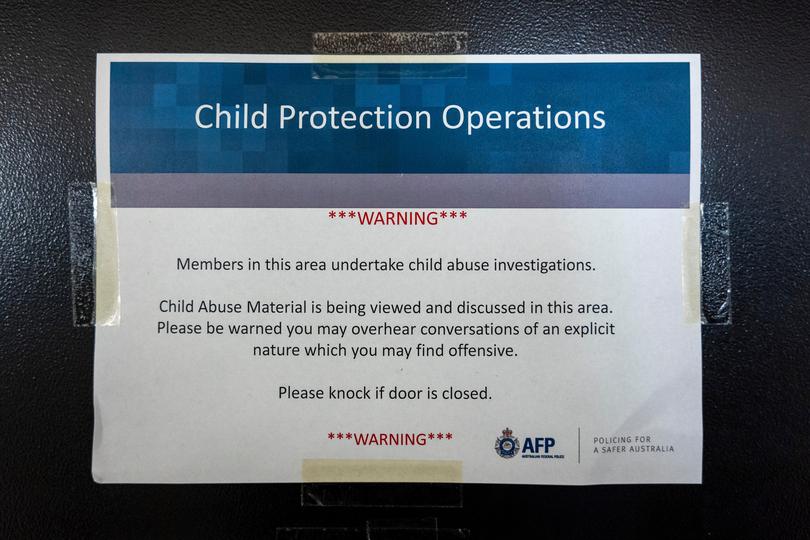

When this victim ID specialist sits down at her desk in the AFP’s Canberra headquarters each morning, she faces an excruciating dilemma.

When Kirsty Clarke sits down at her desk each morning, in the bowels of the Australian Federal Police’s Canberra headquarters, she faces an excruciating dilemma: which child to rescue from horrific sexual exploitation first?

The mother-of-two is a member of the AFP’s little-known Victim Identification Team, whose job it is to locate perpetrators and the children they abuse in sexual exploitation material that has been seized during the execution of search warrants.

The small and predominantly female team is a mix of professional members and sworn police officers who are “passionate about their crime type” and have worked in child protection for years.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.These women spend their work lives analysing horrific photos and videos of child sexual exploitation and abuse to identify perpetrators and put a name to their victims so they can be saved.

Each day Ms Clarke and her colleagues are confronted with an overwhelming amount of material to examine.

“We are seeing a huge volume of that type of material involving children from newborns, right up into teenagers,” she said.

“We need to work out where to focus our time so I try to prioritise the most vulnerable which, for me, is children without a voice, who can’t speak up (because they are pre-verbal).

“That would be the highest priority for us but that is a moral dilemma because we see abuse of very young children through to teenagers, and who says that one’s worse than the other? They’re not.”

The victim identification specialist said the team also prioritises “contact offences” where children are in immediate danger.

“That is the violent sexual assault of children with a perpetrator in the room because we need to remove the child from that person,” she said.

“With the newborns, it’s usually someone known to the child and obviously someone in contact with them.

“Then you’ve got the blackmailing, the sextortion and (remote online) exploitation of young people, which is a huge trend that we’re seeing.”

The Victim Identification Team provides specialist support to the AFP’s Joint Anti-Child Exploitation Teams around the country, who are faced with an explosion of child sexual abuse material.

“I think it’s because offenders have more access to it and it’s more readily available,” Ms Clarke said.

“Back many years ago, the abuse was still happening, but the internet has allowed it to be shared with other offenders.

“They find their communities as well. They talk to each other. They’ve found their people, essentially.”

When JACET investigators execute a search warrant, seized devices — computers, tablets and hard drives — are sent to the forensic unit where the contents of each device are uploaded to a software program.

From there, Victim Identification Team specialists — mostly mothers — painstakingly analyse the files to identify those involved in the production and distribution of child exploitation and abuse material.

Each image and video they review represents a crime scene that could be anywhere in the world.

Ms Clarke said the material she sees has been produced by offenders from “all walks of life” – who are well “camouflaged” into society – and involves the abuse of both boys and girls.

Her grim job is to forensically identify clues in the material that will pinpoint where the crime occurred and identify those involved.

“I look for clues such as what children are wearing, things that we can see in the background and what they’re actually saying in the videos. We do a lot of analysis on the audio,” she said.

“We’re looking for specific products that would narrow down where that child might be located by working out where in the world that product is made.”

Other clues Ms Clarke looks for include types of power-points, plants, furniture, fabrics and buildings.

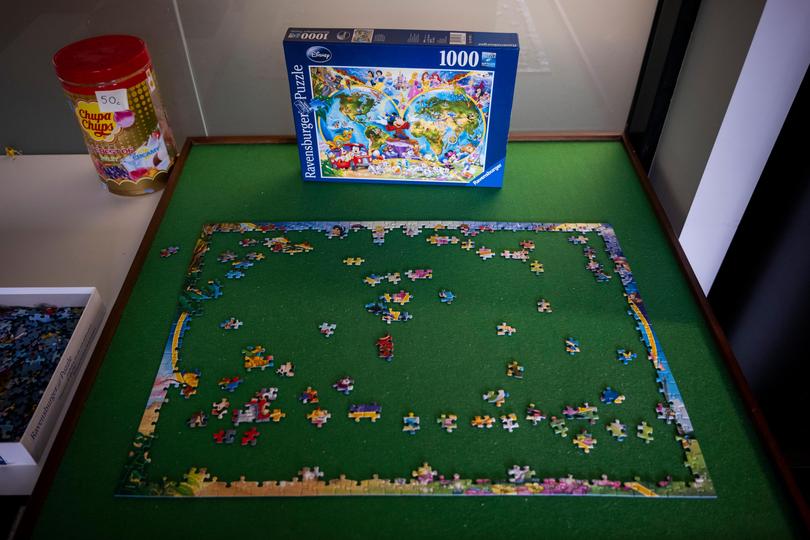

“We start to build a series of clues,” she said.

“We’re putting all the pieces of that puzzle back together to try to pinpoint the location of that particular child.”

The 37-year-old, who has worked in this field for 12 years, said that often the material her team receives lacks intel.

“It can be difficult because sometimes we won’t see a lot of clues,” she said.

“So we’ve got to really rely on what we’re seeing and the data that sits behind that.

“It’s a pretty painstaking process, to actually be able to say, this child is located in this city and we believe the offender to be this person.

“That takes a lot of work to get to that place. It can be quite quick or it can take months or years.”

If the material is information-rich, the case might be cracked quickly.

“When we see an Australian child in the material, it’s all hands on deck,” she said.

“Everyone will drop everything to look for that Australian child.”

If a non-Australian child is identified, the AFP will swiftly have its international partners execute the warrant.

“It can sometimes happen pretty fast,” she said.

“We have had cases solved overnight but they’re pretty rare to be honest.

“We’re looking at offenders who are particularly good, and becoming better, at hiding who they are.

“They’re very deceptive individuals, so we don’t see those quick turnarounds very often.”

Ms Clarke said she often has limited information, apart from what she can see in the material.

She rarely knows where the exploitation material was hosted on the internet so has to “think outside the box” to figure out its origin.

“For us, because we’re looking at the back end of it, there’s no IP address connected to the material, because we’re just getting a huge computer,” she said.

“It’s extremely difficult and there are many jobs that we simply don’t know where (in the world) that child is.

“We work very closely with the Interpol team. We put all that material up on their international child sexual exploitation database and we get help from other victim ID specialists around the world.

“We need as many eyes on the material as possible.”

In 2022, Ms Clarke received a trove of material from devices seized during a search warrant executed in Canberra.

One of the videos police obtained showed a prepubescent girl being followed by an offender, who was also filming, as she walked through an apartment building before he attacked her on a stairwell.

“Our team worked on that video for quite some time but we could only narrow it down to an Asian country,” she said.

“About a month later, I went over to the Interpol Taskforce where a lot of victim IDs specialists from around the world come together.

“I took that video over there and relied on some of the experts from Asian countries.

“What I didn’t recognise, another police force recognised, and we were actually able to find that apartment block.”

The case was quickly referred to police in that country.

“We found her so she’s been rescued and he’s been arrested,” Ms Clarke said.

“And as a result, there’s been multiple offenders and multiple other victims identified from his computers.”

From the devices seized during that particular Canberra job, Ms Clarke has referred 62 cases to overseas agencies, three offenders have been arrested and 14 victims have been removed from harm.

“They don’t have to live in that fear anymore,” she said.

While “inherently resilient”, Ms Clarke admits that exposing herself to such horrific material can take a toll.

“You’ve got to remember that we’re viewing a crime scene so I have trained my brain to, in a sense, remove the child, and I focus on the crime scene, and what we’re seeing around it,” she said.

“I need to remember why I’m viewing it and I don’t over expose myself. I never listen to any videos unless I absolutely have to and I’m able to compartmentalise very well.

“But we’re human beings. You can’t not have a reaction to something so indescribably horrific.”