The backroom deal that delivered Australia’s atomic ban was done when ‘nuclear’ was a dirty word

In the shadow of Chernobyl and French weapons testing in the Pacific, ‘nuclear’ was a dirty word back when Australia’s atomic destiny was decided in the form of a Commonwealth ban.

Back when Australia’s atomic destiny was decided in the form of a Commonwealth ban on power production, nuclear was considered a dirty word.

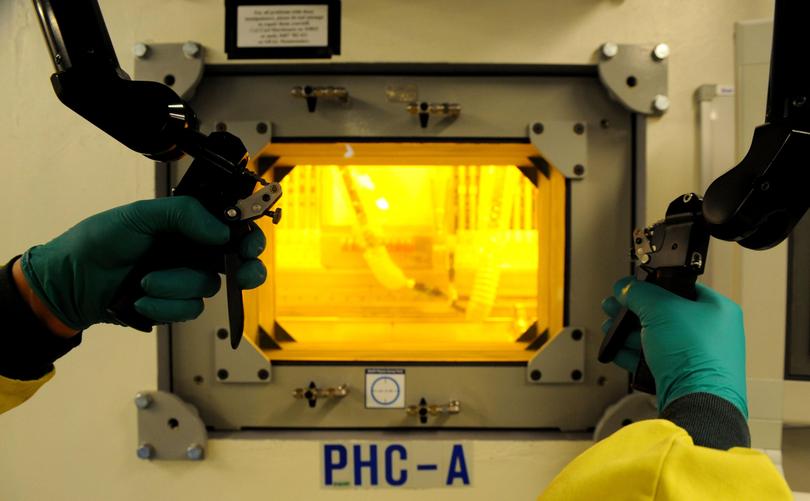

It was 1998 and then prime minister John Howard was wedged into a deal with the Greens and Democrats in order to build a new nuclear facility in Sydney, the site of Australia’s only reactor since 1958 which is used for medical applications such as radiation treatments and x-rays.

In order to get a new reactor at Lucas Heights, 40km south of the CBD, Mr Howard agreed to a last-minute amendment to the National Radiation and Nuclear Safety Act after a debate that lasted less than half an hour and introduced legislation banning any more nuclear facilities from being built in Australia.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.

Just over a decade since the Chernobyl disaster and as Midnight Oil frontman Peter Garrett was publicly celebrating a victory lap after France had recently stopped its nuclear weapons testing program on the islands of our near neighbours in the Pacific, a nuclear ban was politically palatable.

In the dying days of his long prime ministership in 2007, Mr Howard tried to start a new conversation about nuclear energy and repealing the moratorium but it failed to cut through and Labor swept into office after his 11 years at the top.

Effectively nuked, the argument lay idle until Wednesday when Opposition Leader Peter Dutton unveiled his cornerstone election pitch: seven nuclear power plants across five states with the first to begin operations between 2035 and 2037.

Overturning the moratorium and countering the state-based bans in NSW, Queensland and Victoria are among the key initial challenges of carrying out the Coalition’s bold plan to get nuclear into our energy mix.

Labor premiers across Australia and some Liberal opposition leaders said they wouldn’t support any change in State laws to let nuclear take hold with NSW Premier Chris Minns adamant he has the legal power to keep a ban in place.

“If there’s a constitutional way for a hypothetical Dutton government to move through the state planning powers, I’m not aware of it,” Mr Minns said on Wednesday.

Constitutional law expert Greg Craven said Commonwealth law would trump State legislation. Professor John Quiggan from the University of Queensland said this might take the form of the Commonwealth using its Defence powers, such as were implemented in the post-war years to build the Snowy Hydro, to overrule the states.

“But of course, this would still require a lengthy period of litigation if the states still opposed the legislation,” said Prof Quiggan.

“They could potentially override it, but using a defence power would also be politically risky in the sense that they’d have to make some kind of clear commitment on nuclear weapons one way or another.“

Nuclear engineer Jasmin Diab said overturning the Federal moratorium was essential for Australians to engage fully in the upcoming debate.

“At the moment, no government wants to invest taxpayer resources into investigating possibilities of nuclear when there’s a legislative ban,” Ms Diab, the president of Women in Nuclear Australia, told The Nightly.

“You see it in the discussions we’re having around nuclear, we are missing a lot of the expert voices because a lot of our nuclear experts work in government.

“What I’ve been saying a lot is lifting the ban doesn’t necessarily mean Australia will go nuclear, but it allows us to talk about it on a living level playing field.

“We are missing a lot of the important voices around nuclear and we’re missing a lot of the detailed analysis.”

The great shame, Ms Diab said, was that the argument had now become entirely political.

“The problem is that politicians ruin a lot of great discussions with their ideology,” she said.

“It’s so polarising now when energy policy shouldn’t be polarising. It should be, what’s the best for our country.”

Nationals Senator Matt Canavan now supports nuclear after earlier opposition and has been pushing for the moratorium to be lifted for some years.

“We got this ban because of a deal in the middle of the night between Labor and the Greens. There were no committee processes, there was no consultation,” he said.

“The bill was to produce new medicines for all Australians. There was no prospect of nuclear power being generated at the time and that’s why our government eventually accepted the amendment because it was a difference between people having access to nuclear medicines or not.

“We have an accidental ban on nuclear power, not something that was well considered or thought through.

“The Australian people never voted on whether to have a ban on nuclear power.”