Hertha Metals: Startup backed by Gates says its green steel will be cheaper than regular after breakthrough

A startup backed by tech billionaires Bill Gates and Vinod Khosla says it has successfully tested a new approach for making steel that minimises planet-warming emissions without raising costs.

A startup backed by tech billionaires Bill Gates and Vinod Khosla says it has successfully tested a new approach for making steel that minimises planet-warming emissions without raising costs above traditional steel.

Hertha Metals, based in Conroe, Texas, says it now can produce one ton of green steel per day in a pilot facility outside Houston that takes fewer steps and resources than existing methods. While the volume is insignificant, the startup describes the output as a crucial milestone for a technology that’s only a few years old.

Hertha will begin constructing a larger demonstration plant next year in Texas with an annual capacity of more than 9000 tons. It expects to move to commercial production by 2031, at which point it says it will be able to produce green steel cheaper than traditional steel.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Steel production is a major culprit driving global warming, releasing more carbon dioxide than shipping and aviation combined. A number of companies are working to lower emissions from steel, yet green supplies remain small.

Stalled growth in clean hydrogen production, which some green steel producers need, and a sharp turn in US climate policy under the Trump administration are now slowing momentum. Even if all announced green steel plants materialised by the end of the decade, they would account for 6 per cent of what global steel mills produce today, according to an April report published by BloombergNEF.

Part of that sluggish transition is due to the hefty cost of green steel, says Laureen Meroueh, founder and chief executive officer of Hertha Metals.

“Creating something solely based on being a benefit for the climate is not enough in these commodity industries,” she says.

Hertha’s expansion comes as many others in the sector have scaled back their ambition. Globally, investment for new green steel projects more than halved in 2024 to $US17 billion ($26b) registering its steepest annual decline in six years.

Ms Meroueh says that 30 per cent of that added capacity in Texas will be used to produce green steel. The remaining capacity will be used to supply high-purity green iron to American manufacturers of rare earth magnets, which are used in computers, electric cars and medical imaging devices.

A persistent shortage in the US makes high-purity iron a valuable product, Ms Meroueh says, and she expects Hertha’s demonstration plant to break even or even turn a profit.

To reduce their carbon footprint, some green steelmakers capture CO2 from conventional steel mills, which is what India’s Tata Steel has done.

Others, such as Swedish startup H2 Green Steel, replace the coal widely used in conventional steelmaking with green hydrogen, a carbon-free fuel.

There are also startups, including Colorado-based Electra, that use emissions-free electricity to produce green iron, then convert that iron into green steel in electric arc furnaces.

But none of them have broken away from a two-step process of steelmaking that involves reducing iron ore before turning the iron into steel.

Hertha takes a different approach.

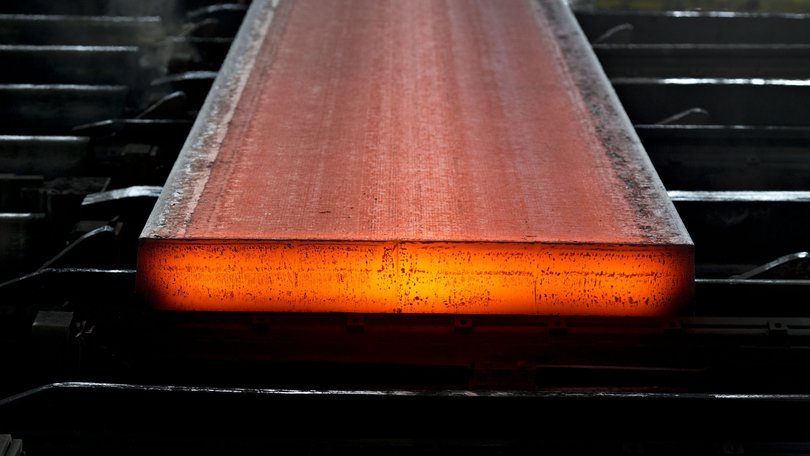

The startup melts lumps of iron ore in a furnace at a temperature of around 1600C using electricity, while introducing natural gas into the furnace and splitting it into carbon and hydrogen.

It also relies on patent-pending methods to influence how the chemical elements in the furnace react to one another.

With all of that happening simultaneously, Hertha says it can go from iron ore to steel in one step, bringing down costs.

Simplifying steel production is an “ambitious attempt,” says Allen Tom Abraham, who leads sustainable materials research at BloombergNEF.

Despite the fact that the industrial steelmaking technique has been around for more than a century, Mr Abraham says that many conventional steel mills still describe their furnaces as the “black box,” due to the challenge of fully understanding the chemical reactions going on inside.

It also remains to be seen whether Hertha’s approach can deliver on its promise as it tries to scale up.

“For many emerging technologies, what works well on a pilot scale doesn’t necessarily work well on an industrial scale,” Mr Abraham says.

Ms Meroueh is tight-lipped about exactly how Hertha’s technology works, citing proprietary concerns.

When natural gas and renewable-generated electricity are used, Hertha estimates that it can cut carbon emissions by more than 50 per cent compared to traditional coal-based steelmaking.

If the company uses hydrogen made with renewables, it claims to almost completely decarbonise the process. But it is unclear when the company would be able to make that switch, since green hydrogen remains prohibitively expensive.

Mackenzie Cool, a senior associate working on industrial transition issues at think tank RMI and climate tech accelerator Third Derivative, sees Hertha’s work as “a promising innovation for cleaning up steel production.”

Methods that zero out carbon emissions in steelmaking could cost more than the status quo even in 2050, according to BNEF estimates.

That cost gap has posed a major hurdle in technology deployment. German conglomerate Thyssenkrupp warned earlier this year that its multi-billion-dollar steel plant using green hydrogen risks becoming economically unviable.

Cleveland-Cliffs Inc, America’s second-largest steelmaker, also announced in June that it has cancelled its $US500 million plan to build a hydrogen-based green steel project in Ohio.

“Techno-economics is the most critical thing” for climate tech deployment to scale, says Rajesh Swaminathan, a partner at Khosla Ventures.

Hertha raised more than $US17 million and plans to launch a series A funding round later this year to finance its expansion.

Originally published as Startup claims its green steel will be cheaper than regular steel