JACKSON HEWETT: Why markets have the Reserve Bank stuck in a holding pattern on interest rates

Australian homeowners desperate for a bit of extra cash from interest rate relief when the Reserve Bank met earlier this month might have been better served throwing whatever cash they had left over into the stock market.

In May, when the Bank cut interest rates by a quarter of a per cent to 3.85 per cent, the average Australian mortgage holder with a debt of $642,158 and an average mortgage rate of 5.93 per cent would have been better off by $97 per month. That’s not going to move the needle too far.

But if that same mortgage holder went back to the bank and used that lower rate to borrow more against the house, they could have released more than $15,500.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Had they done that, and put that money into the US S&P500, they would, on paper, be $1260 richer. Even investing in the ASX 200 would see them $436 better off. That’s a lot more than $180 in reduced interest.

While 90 per cent of Australian mortgage holders are using that extra cash to pay down a fraction of their total debt, investors are pinning their ears back and bidding stock markets to record highs.

That risk appetite is complicating the picture for the Reserve Bank of Australia, which tracks market reactions to current economic events to help in its deliberation.

In May, the Bank released a paper detailing three scenarios that might occur as a result of Trump’s trade war.

The worst of those was a global financial contagion as a result of “higher levels of tariffs . . . imposed permanently, causing global sentiment, growth and asset prices to fall sharply”.

Back then the world was facing the prospect of tit-for-tat tariffs of 150 per cent between the US and China. Fortunately, both have backed down but the US will still impose the highest tariffs since the 1930s.

China is still facing a 30 per cent tariff, Canada 35 per cent and the other big US trading partner, the EU, is looking at 15-20 per cent, which would be “a total car crash for European exports”, as one economist put it.

Reciprocal tariffs are being contemplated by all of those nations.

That sounds a lot like the RBA’s fears coming to fruition but instead of asset prices falling sharply, they have instead soared eight per cent since that warning.

Stock markets are effectively a barometer of future economic conditions — it only makes sense to pay higher and higher valuations for a company’s stock if the economy is growing, not about to crash.

It looks like the belief in the TACO trade — Trump Always Chickens Out — is far stronger than the fear of the alternative.

So baffling was/is the apparent disconnect, that it was the RBA’s first order of business.

“Members commenced their discussion of financial conditions by observing that financial market pricing continued to imply a relatively benign outlook for global growth and inflation,” the RBA minutes stated.

They noted bond yields — the most watched predictor of risk — had fallen back to pre-tariff levels, equity prices were at record highs, and measurements of equity risk low.

“Members discussed whether current financial market pricing reflected a degree of complacency on the part of market participants about the impact of these factors on the outlook for the global economy or suggested that earlier pessimism might have been overstated.”

Perhaps the traders are seeing something the Bank didn’t, with a recent report from JP Morgan suggesting the global economy grew at its longer-term trend of a 2.4 per cent annual rate in the first half of this year.

Global supply chains have learnt the lesson of COVID, a Wall Street Journal article suggests, and are able to roll with the trade punches. Investments have continued to be made, trade has been redirected and importantly, governments have been propping up their economies.

There’s enough momentum abroad and in Australia to give the RBA pause to see what happens next. In its minutes the Bank noted that employment is still strong, spending is improving and house prices starting to climb. Despite the sense the economy is stuck in low gear, there is enough juice to keep inflation a little higher than first predicted.

The Bank concluded that interest rates are still “modestly restrictive” but hardly a brake on the economy.

The minutes show a Reserve Board that wants to cut, but uncertain about where the global economy will land.

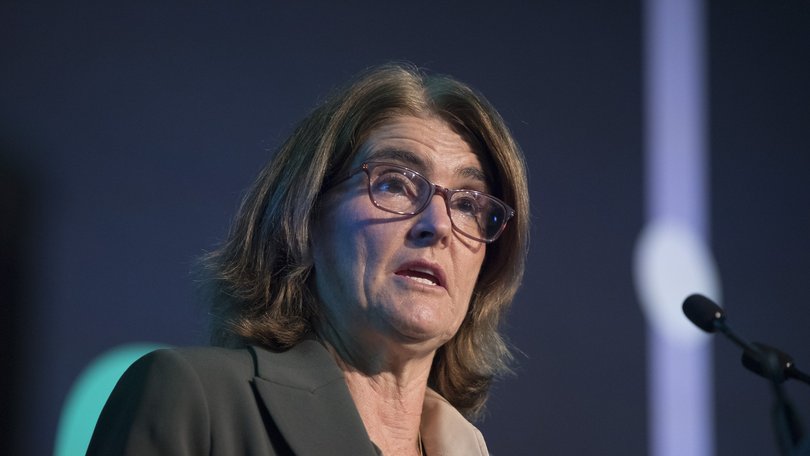

In her press conference following the rates decision, RBA Governor Michele Bullock was adamant that the the Bank wasn’t ‘keeping its powder dry’ in the event of a global downturn, which means that barring any significant event between now and 12 August, there will be a full focus on the domestic economy.

On that front, Australia’s economy is like lukewarm porridge and a 0.25 per cent rate cut won’t do much to change that.

Maybe that’s why productivity reared its once again.

The minutes make an almost tacit admission that rates can only do so much, and unless the productivity problem is solved, the economy is facing a low growth future.

“The (Bank) staff’s forecast for output growth continued to assume that annual productivity growth would pick up, despite no rise in productivity since 2016. Members noted that this assumption materially influences the medium-term outlook for growth in the economy’s supply capacity, incomes and demand,” the minutes said.

“If productivity growth proves to have been persistently lower than had been the case historically, the recent subdued outcomes for GDP growth may not have been far below the rate of growth in supply capacity.”

Translation: the economy can’t grow any faster than its ability to be productive. That’s not encouraging when productivity is at 60-year lows.

Over to you Jim Chalmers.