THE ECONOMIST: Why Australia is not yet a critical minerals powerhouse

On the face of it, Australia should have a huge advance in the race for critical minerals; and yet we can’t seem to get ourselves off - or, rather, out of - the ground and running.

On the face of it, Australia should have a huge advance in the race for critical minerals. Its red centre holds large reserves of the minerals and rare earths that are vital for green and military technologies. Its centre-left Labor government wants to dig and process more of them. It should be the perfect match.

But Australia is struggling to get its critical minerals out of the ground.

A string of its lithium and nickel mines have closed this year. Refineries are also in trouble. In July BHP, a mining giant, said it would close its nickel-processing facilities in Western Australia. Weeks later, Albemarle, an American company, announced it was scaling back a lithium refinery.

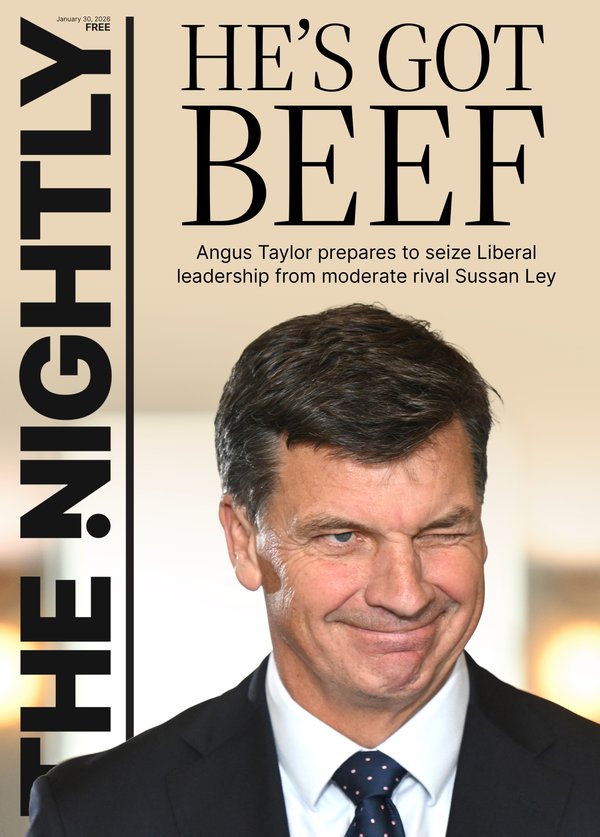

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Ostensibly the problem is a market crash. Demand for electric vehicles, which use these minerals, is weaker than expected. And supplies of minerals have soared, driving down prices.

Australian miners see a bigger hand at work. China produces more than half the world’s rare earths and refines almost all of them. It subsidises rare-earth companies. Where it lacks its own big critical mineral deposits, it has invested abroad — including in the Indonesian nickel that is flooding the market. It buys and refines the lion’s share of lithium. This lets China force down prices, says John Coyne of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute.

Australia’s rare-earth miners are dangerously exposed, complains Tom O’Leary, chief executive of Iluka Resources, one such group. In 2022 China issued a directive for its producers to “guide product prices to return to rationality”. Rare-earth prices have since plunged by more than two-thirds. This makes it hard for competitors to be profitable, says Mr O’Leary.

Chinese investors are also accused of using shady methods to secure access to Australian supply chains.

Last year Australia’s government barred a Chinese-linked fund from increasing its stake in Northern Minerals, a miner, on national-security grounds. Shares were subsequently purchased by several other funds. After an investigation, the government determined that they were linked to China and ordered them to divest their holdings in June.

For Australia, it is not just the potential for lucrative mines at home that China’s dominance severely threatens. It’s also about its own security of supply.

China cut off rare-earth exports to Japan during a diplomatic dispute in 2010, and curbed exports of gallium and germanium, used in semiconductors, last year.

Western countries face “an existential risk around security of supply”, says Mr O’Leary.

So far, Australia’s answer is to support miners with cheap loans and grants. It promises them tax breaks under a new industrial policy. But the help only goes so far.

The government lent Iluka A$1.25bn in 2022 to open a rare-earths refinery. On August 21st Iluka declared that it needs more funding to complete the facility.

There is still a long way to go to end, or even reduce, reliance on China.