The Economist: An American sovereign wealth fund is a risky idea

Donald Trump’s latest proposal has worryingly broad support.

Not long ago America’s main concern with sovereign-wealth funds was how to regulate these large pools of money controlled by foreign governments. Now, seemingly overnight, the hot new idea in Washington, DC, is that America should join the club. It is easy to understand the allure. A well-managed SWF can, in theory, let the government direct more cash towards its strategic aims, without—if returns are strong — the need to raise taxes. In practice, achieving this balance is difficult. In America a SWF looks like a risky solution to a problem that does not truly exist.

As is often the case these days, credit for the idea’s popularity goes to Donald Trump. In a speech on September 5th Mr Trump said that he wants to create an American fund if he wins November’s election. Characteristically, he promised it would be the greatest such fund in the world. Critics were just starting to mock the notion when it turned out that Democrats were thinking along the same lines. President Joe Biden’s advisers have been working on a blueprint for a fund to promote America’s national-security interests, including by investing in emerging technologies.

To understand SWFs — and why America does not need one — consider two issues: the source of their wealth and how they use it. Traditionally, funds have been the preserve of countries flush with either commodities (Norway and the United Arab Emirates) or foreign-exchange holdings (China and Singapore).

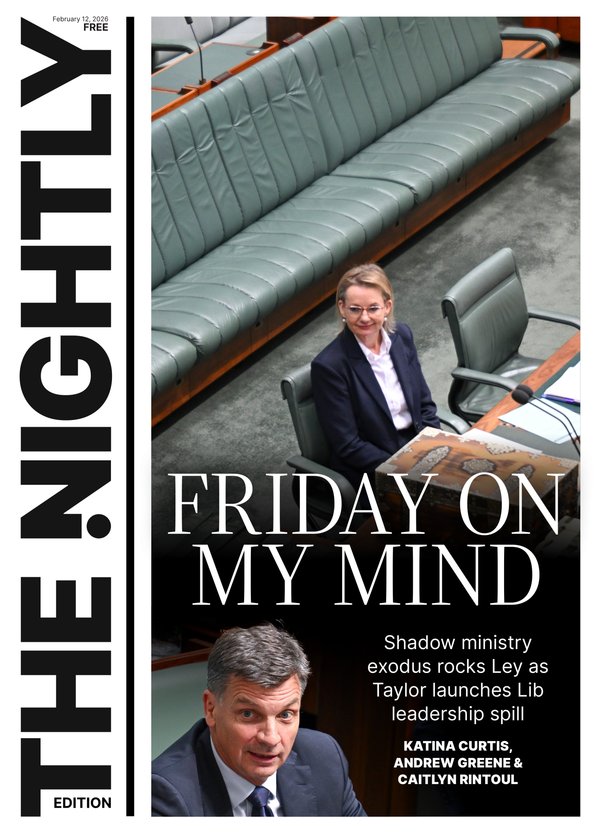

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.You might assume that the creation of a wealth fund is proof that these countries are rich. To some extent, that is true. But the funds also reflect scarcity: resources are finite, and good financial management is needed to ensure future generations benefit from the current bounty. (In the case of countries with bulging foreign-exchange holdings, their resources are proceeds from intervening in markets to restrain their currencies from appreciating.)

America has no such windfall to manage. Although the country is an energy superpower, just a tenth of its oil and gas drilling occurs on federal land. Royalties from this brought in $US17 billion ($25.5b) of revenue for the government last year. After disbursements to states and tribes plus environmental costs, only $US7b went to the Treasury. The government could approve more drilling on federal land, which Mr Trump has promised, or charge higher royalties, which Mr Biden has done, but revenue increases would be incremental. Even if federal receipts from drilling were to double, they would still amount to less than 0.1 per cent of GDP. By contrast, the Norwegian government’s earnings from oil are about 10 per cent of GDP.

There is another way in which America could secure more funding for its SWF: by earmarking a broader array of revenues for the fund via, say, special bond issues. Yet this only drives home the point that wealth funds ultimately sit on government balance-sheets, and that their funding, whether from oil royalties or bond sales, could just as easily go to something else. The decision would, in effect, be either to spend money capitalising the fund, rather than on schools or highways, or to issue more debt—and America is already borrowing plentifully thanks to an annual budget deficit of about 7 per cent of GDP.

Once money is allocated to a SWF, the big question is how the fund’s managers, acting on government instructions, put it to work. For countries trying to ensure that resource bonanzas survive for the benefit of future generations, the ambition is to secure a good return. Typically, that requires investing in a wide range of assets, from equities and bonds to property and private credit. Some wealth funds are also tasked with making strategic investments on behalf of their countries. Gulf states, for instance, are using their funds to build up their renewable-energy industries.

Messrs Trump’s and Biden’s advisers reason that America should likewise have a fund that generates extraordinary profits and can be directed at strategic initiatives. On closer scrutiny, however, their logic comes apart. Although getting good returns on public assets sounds laudable, it is necessary to consider the opportunity cost. Every dollar assigned to the fund could instead have been invested directly by the public had they been taxed less. Implicitly, the government would be saying that it is better at directing capital than citizens and businesses. If that were true, why stop with a small wealth fund? Increase tax rates so that the government has yet more resources to allocate centrally—an argument that no sane politician would ever make.

There is one specific, limited area where America could experiment with a SWF-like model: boosting returns on the assets that back its social-security system. Indeed, a bipartisan group of senators last year floated this idea. The social-security system is low on money, and the law restricts its managers to investing their reserves in government bonds. Giving managers a bit more flexibility might help, though it would expose them to more risk.

Return to sender

Creating a fund for strategic projects is another thing entirely. Such a fund would be redundant. Mr Trump wants one to build airports and highways, ignoring the fact that the government is in the midst of a $US1 trillion-plus infrastructure splurge. Mr Biden’s advisers, for their part, have ruminated about using a fund to promote technological pre-eminence and energy security. They may recall this is the exact purpose of the $US1trn-plus industrial policy that is the centrepiece of their administration’s economic agenda.

To be fair, a SWF would have one clear advantage over relying on existing budgetary mechanisms to pay for strategic initiatives. It is fiendishly hard to get serious legislation through Congress, and follow-up questions in committee hearings can be uncomfortable. A sovereign fund would, if big enough, provide a way round these pesky democratic procedures. Ultimately, though, that is not an attraction for anyone other than politicians.