THE ECONOMIST: The trouble with MAGA’s manufacturing dream

Donald Trump underestimates the difficulty of producing in America - and how his own policies will make it harder.

In the late 1940s, as the industrial capacity of Europe and Japan lay in tatters, America accounted for over half of global manufacturing output, with much of the world heavily reliant on its wares. Last year it accounted for little over a tenth, and imported $US1.2 trillion ($1.8trn) more in merchandise than it exported — to the displeasure of its president.

By placing America’s enormous market behind a wall of tariffs, Donald Trump hopes to force companies to relocate production there, making it once again a manufacturing powerhouse. Various businesses, from Eli Lilly, a pharma giant, to Schneider Electric, a maker of electrical equipment, have recently announced plans to oblige Mr Trump.

On April 28 IBM piled in, saying it would invest in making mainframe and quantum computers in America. Yet others, from PepsiCo, a pedlar of beverages and snacks, to Diageo, a booze business, have warned that tariffs will squeeze their profits. Mr Trump underestimates how difficult it will be for firms to shift their factories to America — and fails to appreciate the various ways in which his policies are likely to backfire.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Start with the labour supply. The average pay for a production worker in America is more than twice the level in China and nearly six times that in Vietnam. Yet those wages are still not attracting enough Americans into manufacturing. In the Census Bureau’s most recent survey of factories, a fifth said that an insufficient supply of labour was contributing to their inability to operate at full capacity.

Foreign bosses hoping to manufacture in America lament the paucity of skilled workers such as welders, electricians and machinery operators. This month C.C. Wei, boss of TSMC, a Taiwanese chipmaker, said its effort to produce chips in Arizona was “being constrained by the labour shortage” in the state.

Anyone counting on automation to solve the problem risks being disappointed. Howard Lutnick, Mr Trump’s commerce secretary, recently insisted that “the army of millions and millions of human beings screwing in little, little screws to make iPhones” would soon come back to America, where the work could be automated.

Yet a robotic overhaul of American manufacturing may still be a long way off. In 2023 there were just 295 industrial robots for every 10,000 manufacturing workers in the country, according to the International Federation of Robotics, an industry association. Although that was up from 255 in 2020, it was dwarfed by China’s 470 and South Korea’s 1,012. Contrary to Mr Lutnick’s claim, Apple is now said to be planning to assemble America-bound iPhones in India.

The difficulty of building factories is a second barrier to manufacturing in America. Annualised spending on factory construction has doubled, adjusting for inflation, over the past four years, spurred on by subsidies offered by the previous administration to makers of chips and various green technologies.

Many of the resulting projects, however, have been mired in delays or shelved altogether. Solvay, a European chemicals firm, has paused construction of a plant in Arizona intended to make electronics-grade hydrogen peroxide for semiconductors. Pallidus, an American manufacturer of chip components, has axed plans to build a factory in South Carolina.

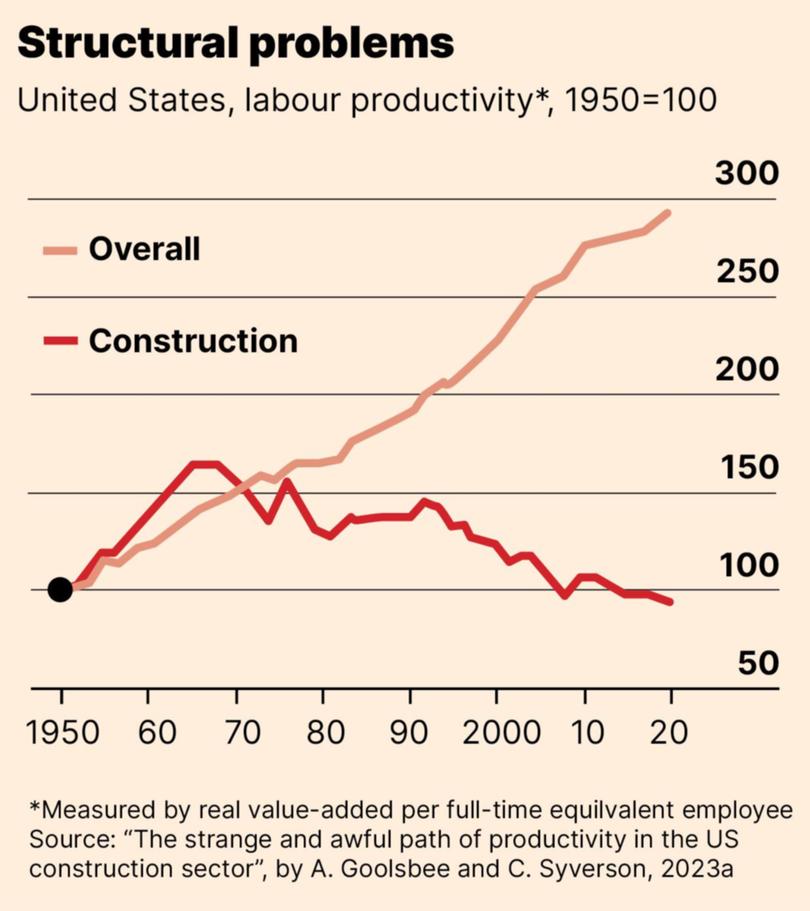

That reflects the troubled state of construction in America. According to a 2023 paper by Austan Goolsbee and Chad Syverson of the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business, productivity in the sector, measured as output per worker, has fallen by two-fifths from its peak in the 1960s. The authors blame excessive regulation, NIMBYism and a lack of incentives to deliver projects on time, among other things. Labour shortages have also buffeted the construction sector in recent years.

In the meantime, America’s existing factories are ageing. Over half of the roughly 50,000 manufacturing facilities across the country are more than three decades old; the average plant was built some 50 years ago.

America’s inability to build has also resulted in ageing and overextended infrastructure — a third barrier to manufacturing in the country. Much of the electricity grid was constructed in the 1960s and 70s and is at or near the end of its useful life, a factor behind increasingly frequent power outages.

Meanwhile, factories seeking a new connection to the grid face years of delay. Transport infrastructure is no better; one in three bridges in America needs to be replaced or repaired, according to a study last year by the American Road & Transportation Builders Association, an industry group. It is a far cry from the slick transport networks that grease supply chains in East Asia.

Spanners in the works

Instead of fixing these problems, Mr Trump looks likely to make manufacturing in America an even trickier proposition.

His efforts to clamp down on immigration and deport those who have made their way into the country illegally risk worsening labour shortages both in factories and on construction sites. His tariffs are raising the cost of everything from the steel needed to build manufacturing facilities to the machinery that fills them. They are also making it more expensive to import raw materials and parts; almost a third of the intermediate inputs used in American manufacturing are imported.

Then there is the uncertainty created by Mr Trump’s tariff flip-flopping. Many bosses say they are still waiting for clarity on what duties will be imposed on which countries before they make any changes to their production footprints.

Although factory jobs in America have dwindled, the country has continued to play a central role in global supply chains, including by developing world-leading intellectual property in areas from semiconductors to pharmaceuticals. Nearly $US1trn-worth of research and development takes place in America each year, more than in any other country.

By jeopardising America’s trade ties, Mr Trump puts all that at risk. Instead of yearning for a return to the past, the president should let America get on with designing the future.