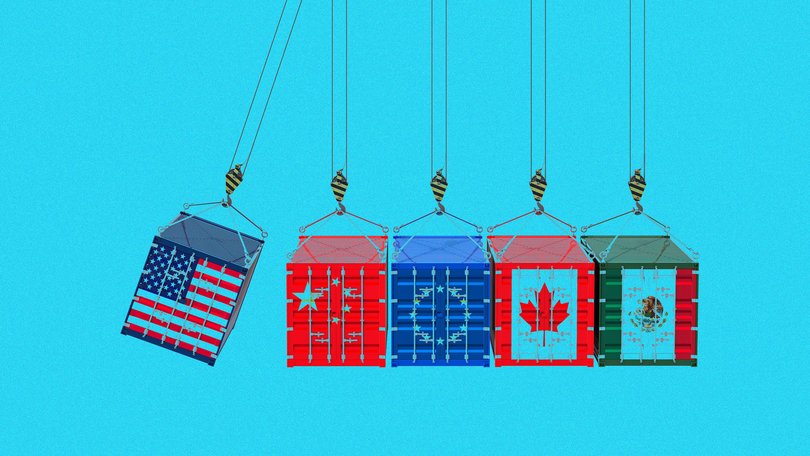

THE ECONOMIST: Who is feeling the pain of Trump’s tariffs?

THE ECONOMIST: Following the launch of US President Donald Trump’s trade war, it now has an effective tariff of over 16 per cent, the highest since the 1930s, and rates could go even higher.

Following the launch of President Donald Trump’s trade war, it now has an effective tariff of over 16 per cent — the highest since the 1930s. And rates could go even higher.

Mr Trump has written strongly worded letters to many of America’s biggest trading partners threatening further levies on August 1.

Who pays for these tariffs?

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Most economists reckon that ordinary Americans will lose out, as prices in shops rise. Mr Trump and his coterie, by contrast, blithely insist that the rest of the world will shoulder the load by cutting their selling prices.

So far, the evidence is giving the know-nothings a glimmer of hope.

Mr Trump’s critics in the economics profession have history and research on their side.

Studies show that when a country imposes duties on its imports, its foreign suppliers often keep their prices roughly the same. The tariff is layered on top. So it was during the first Trump Administration, which slapped tariffs on China and others. A study from 2019 found “complete pass-through of the tariffs into domestic prices of imported goods”.

Some foreign firms are taking a similar stance in response to Mr Trump’s new levies.

In April, Ferrari added up to 10 per cent to the price of its cars. Britain’s Ineos said it would charge more for its Grenadier off-roader. Canon, a camera-maker, has warned dealers to brace for price increases.

But the broader pattern is more benign. There is, for example, surprisingly little evidence so far of tariff pass-through into inflation.

In June, America’s core consumer prices — excluding food and energy — rose by 0.2 per cent on the previous month, below the consensus estimate of 0.3 per cent. Economists have found some evidence of tariff-induced price rises — in car parts, for instance — but they have had to look harder for it than they had expected.

What explains this surprising result?

American firms, not consumers, may be paying for the tariffs by accepting lower profits, suggests research by Deutsche Bank. Some firms also boosted inventories before the tariffs were implemented, allowing them to avoid raising their prices for now.

America’s foreign suppliers may also be sharing more of the load than they did in Mr Trump’s first term.

Nintendo, a Japanese electronics firm, is keeping the American price of the Switch 2 games console at $US449.99 ($680). Many Chinese manufacturers seem prepared to follow Nintendo and absorb duties: Fuling, a supplier of cutlery, says its clients expect it to shoulder part of the increased tariff costs. TIRTIR, a South Korean beauty brand popular with American Gen Zers, has signalled that it can absorb most of the tariffs.

The Bank of Japan tracks the prices of the country’s car exports to America. In yen terms, they have fallen by 26 per cent in the past year.

Some of that decline may reflect exchange-rate movements. An unchanged dollar price brings in fewer yen when the American currency is weak. But that only raises another question: why are Japan’s carmakers not raising their dollar prices more vigorously in response?

More comprehensive data points in a similar direction. The Economist assembled a series on export prices from a number of America’s largest trading partners, including Canada, Germany and Mexico.

In the past, exporters in these countries have shown themselves perfectly willing to raise prices — during the inflationary surge of 2021–22, they hiked them by more than 15 per cent over a 12-month span. Yet in the past year, the average local-currency price of their exports has fallen by 3.6 per cent.

Nothing of the sort happened during Mr Trump’s first trade war.

Why might foreign suppliers be so forgiving?

Some bosses worry more than before about the American consumer. With high inflation such a recent memory, people angrily insist that everything is already too expensive.

Households have little tolerance for paying even higher prices. The opposite may be true of the foreign companies themselves. They are in a good financial position to withstand the tariffs.

Aggregate margins of listed companies in emerging markets have become fatter over the past decade, increasing by over two percentage points. European firms have enjoyed similar gains. These companies can afford to take a small hit to profits — at least for now.

Before long America’s economy is likely to feel the pain of the trade war more acutely. Although some Chinese firms may have lowered their prices, these cuts are not nearly deep enough to offset the huge rise in tariffs they now face, points out Deutsche Bank’s research.

In addition, foreign companies that have borne the costs until now may not be able to bear them forever — especially if, as promised, the Trump administration imposes even higher tariffs on August 1. The president loves defying his adversaries, in the economics profession and beyond. But he is always his own worst enemy.

Editor’s update: On July 27 America reached a trade deal with the European Union that includes a 15 per cent tariff on most EU goods.

Originally published as Who’s feeling the pain of Trump’s tariffs?