The Economist: Why the US Federal Reserve has gambled on a big interest rate cut

It’s a bold move that carries economic and political risks.

The Federal Reserve’s decision to lower interest rates by half a percentage point, announced on September 18, is momentous for two reasons. As the first cut by America’s central bank since it lifted rates to quell inflation, it marks the start of a monetary-easing cycle.

It also represents a bet by the Fed that inflation will soon be yesterday’s problem and that action is needed to support the labour market. For the first time since 2005, one of the Fed’s governors in Washington, DC, dissented from the decision. Michelle Bowman preferred to cut rates by a quarter-point.

When the Fed raised rates between early 2022 and mid-2023, it telegraphed the size of each rise in advance. This time there was uncertainty about how big the reduction would be. A week earlier, market pricing implied roughly 65 per cent odds that the Fed would cut rates by a quarter-point and 35 per cent odds of a half-point.

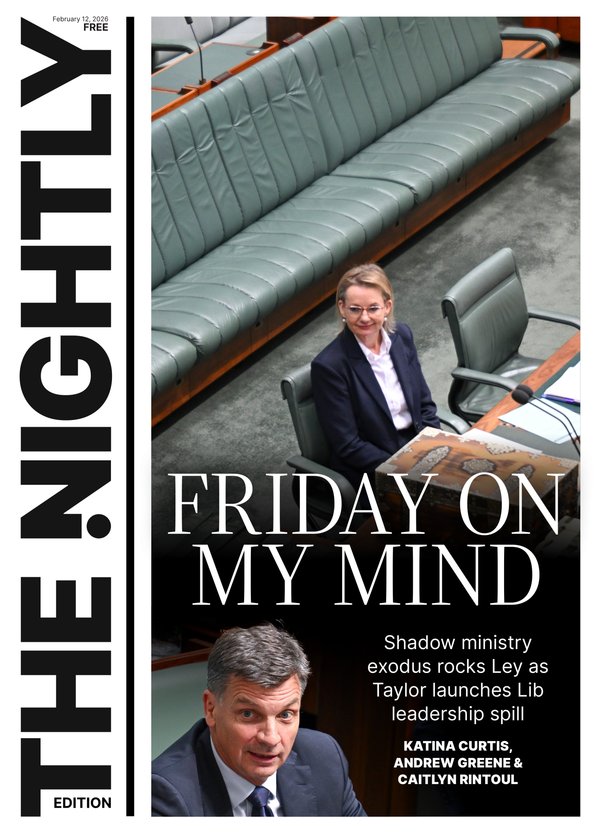

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.By the day before the decision, pricing had flipped, indicating a 65 per cent probability of a half-point cut. The fact that some investors, albeit a minority, were still positioned for a smaller move helps explain why stocks rallied at first after the Fed opted for a bigger cut.

The argument for a half-point cut rested on several pillars. Crucially, the Fed is confident that it is on track to bring inflation under control. Price rises have slowed to an annual pace of 2.5 per cent, not far from its target of 2 per cent. With oil prices sagging and rents rising more slowly, there is a good chance that inflation will soon ease further.

So the Fed’s worries have shifted to the job market. The unemployment rate of 4.2 per cent is low, but nearly a full percentage point higher than early last year. And firms have pared back their hiring. Jerome Powell, the Fed’s chair, portrayed the rate cut as a recalibration of monetary policy in line with a lessening of inflation risks and an increase in unemployment risks.

The Fed’s cut is a form of insurance. It takes months for rate reductions to filter through the economy. Given this lag, and given the expectation that the economy will continue to slow, it makes sense for the Fed to make a bigger move now in order to get ahead of the coming weakness.

The central bank was late in raising rates in 2022. This time, it hopes that starting with a bigger cut will steer the economy towards a soft landing, avoiding the recession which many analysts once thought inevitable. “We don’t think we’re behind,” said Mr Powell. “We think this is timely. But I think you can take this as sign of our commitment not to get behind.”

The Fed’s big cut nevertheless poses some dangers. Despite the cracks in the labour market, the economy as a whole appears to be holding up well. Resilient consumption has put it on track for annualised growth of 3 per cent in the current quarter, well ahead of most forecasts just a month ago.

A hefty rate cut against a strong economic backdrop risks sending the wrong signal to markets. The central bank judged that this risk was manageable. According to projections released on September 18, the median forecast of Fed officials is that they will reduce rates by another 1.5 percentage points by the end of next year. They could easily make fewer cuts if inflation proves to be a more stubborn foe.

Another danger is politics. Coming just before the presidential election, the big rate cut may attract criticism from Donald Trump as a sign that the Fed, a regular target of his ire, is trying to help Kamala Harris.

Yet a quarter-point cut could just as easily have invited a charge from Democrats that Mr Powell had been intimidated by Mr Trump. Mr Powell has long said that he tunes out the political din. He may well need a hefty pair of noise-cancelling headphones in the coming weeks.