THE ECONOMIST: Xi Jinping and China’s plan to beat America in the AI race

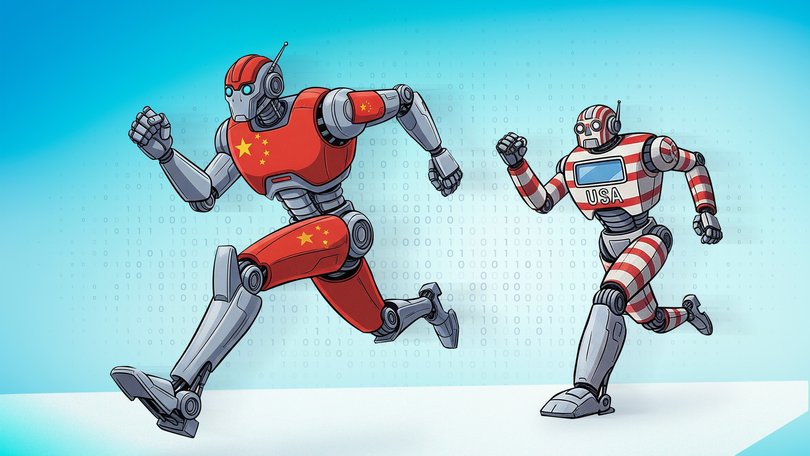

On May 21 JD Vance, America’s Vice-President, described the development of artificial intelligence as an “arms race” with China. If America paused out of concerns over AI safety, he said, it might find itself “enslaved to PRC-mediated AI”.

The idea of a superpower showdown that will culminate in a moment of triumph or defeat circulates relentlessly in Washington and beyond. This month the bosses of OpenAI, AMD, CoreWeave and Microsoft lobbied for lighter regulation, casting AI as central to America’s remaining the global hegemon.

On May 15 president Donald Trump brokered an AI deal with the United Arab Emirates he said would ensure American “dominance in AI”. America plans to spend over $US1 trillion ($1.53trn) by 2030 on data centres for AI models.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.The “DeepSeek moment” in January, when the Chinese firm unveiled a large-language model (LLM) matching the capabilities of an OpenAI model, confirmed that China is snapping at the heels of America. Yet a recent meeting of the Communist Party’s leadership suggests it is preparing for a different kind of strategic race.

“American firms focus on the model, but Chinese players emphasise practically applying AI,” says Zhang Yaqin, a former boss of Baidu, a tech giant, now at Tsinghua University. This focus on practical applications – in factories and for consumers – is how China stole a lead in e-commerce and e-payments.

On May 19 Jensen Huang, the boss of Nvidia, a chip firm, warned America could be left behind again. If American firms do not compete in China as it builds a “rich ecosystem”, Chinese technology and leadership “will diffuse all around the world”, he told Stratechery, a newsletter.

America’s view of AI is often abstract and hyperbolic. LLMs are expected to match humans’ cognitive abilities, with boosters believing this rubicon of artificial general intelligence (AGI) will be crossed in a couple of years. Sam Altman, the boss of OpenAI, reckons the next step could be superintelligent systems that actually surpass human abilities in cognitive tasks.

Being the first to develop a model that can recursively improve itself (some call this “take-off”) may create a decisive advantage comparable to being the first to develop a nuclear bomb. Barath Harithas of CSIS, a think-tank, notes that American planners think “the first country to secure the AGI laurel will usher in the 100-year dynasty”. America’s export controls on semiconductors are there to ensure China comes second.

It is true some Chinese entrepreneurs are also believers in the arms race. Liang Wenfeng, DeepSeek’s founder, has made developing AGI his firm’s mission and also reckons it may arrive as soon as in two years. Less noticed is that the government is betting on a different approach. Mr Liang’s exploits won him a meeting with Li Qiang, the prime minister, in January.

But days later a vice-premier in charge of the party’s science effort seemed to rebuke the American approach, stating: “China will not blindly follow trends or engage in unrestrained international competition.” Last month Qiushi, the most authoritative Communist Party journal, described AGI as a tool “to promote human understanding and transformation of the world”.

In China the term for AGI, tongyong rengong zhineng, typically refers to a “general-purpose AI” that is applied and has multiple uses, rather than to the Western concept of a superhuman, or self-improving system.

In April the party’s Politburo met for its second-ever study session on AI (the first was in 2018). At the meeting, Mr Xi told his lieutenants that China should focus on how it can be applied to everyday uses: more like electricity than nuclear weapons.

At least a dozen prominent researchers and government officials have aired scepticism over the reasoning ability of LLMs. Wu Zhaohui, a former minister of science and the current vice-president of a state think-tank, suggests China needs to explore different paths to AGI. Chinese experts generally expect AGI to take longer to arrive than do their American counterparts, notes Mr Zhang of Tsinghua.

“While American tech leaders often frame AI with utopian aspirations, China’s government appears more focused on using it to solve concrete problems like economic growth and industrial upgrading,” says Karson Elmgren of RAND, a think-tank. The government’s annual work report in March mentions a new campaign called “AI+”, which prioritises firms adopting AI in their existing operations, including physical facilities using automated robots. This mimics the “Internet+” campaign a decade ago to create a more sophisticated digital consumer economy than the West.

This application-oriented approach reflects a shortage of AI talent and chips, or “basic theory and key core technologies,” Mr Xi said in April. “We must face up to the gap.” Liu Zhiyuan of Tsinghua University compared China’s approach to an argument in “On Protracted War”, a series of lectures by Mao Zedong in 1938: a weak opponent can tire out a strong one, and outlast them. On May 8 Qiushi published an article by Tang Jie, also of Tsinghua, advocating China be a fast follower of American innovation, focusing on being cheaper and quicker to create applications.

China’s emerging AI strategy seems to have two parts. One is to undercut the monopoly America has over advanced AI, by replicating Western innovations and releasing the model weights for free, or “open source”, as DeepSeek has done. The idea is that the value AI generates will accrue to those who apply it, not to the model-makers themselves.

By the time AGI arrives, China will be better placed than America, with “robust social applications, search engines, agents, and hardware in place,” according to Kai-Fu Lee, a prominent Beijing-based entrepreneur. He argues that by amassing users and data early, Chinese applications can build a moat that Western competitors will struggle to cross, just as TikTok, a video app, has done.

Alongside the push to deploy AI faster and more cheaply there is an effort to create moonshots that bypass America’s trillion-dollar bet on LLMs. “If we merely follow the well-worn American path — computing power, algorithms, deployment — we will always remain followers,” said Zhu Songchun, boss of the Beijing Institute for General Artificial Intelligence, a state-run laboratory dedicated to advanced AI, in a speech last month.

In April the Shanghai government offered funding for researchers advancing towards AGI using new kinds of architectures, such as models that interact with the real world through imagery, others that can control computers with the mind, or as-yet theoretical algorithms to emulate the human brain.

Will China’s approach work? A new IMF study concludes AI could boost America’s economy by 5.6 per cent in ten years’ time, compared with 3.5 per cent for China, largely because China’s relatively small services sector means that, even if AI diffuses fast in manufacturing, the productivity gains are capped.

Yet what is clear is that China is accelerating down a different track. One sign of this is Apple: in order to reverse a decline in its revenue in China it desperately needs a local partner to provide AI services which customers now expect. But recent reports suggest the American government may block it from doing so. Without local AI applications, American tech products, such as the iPhone, risk becoming also-rans in China, and perhaps, in time, elsewhere.