THE NEW YORK TIMES: Chinese food and drink chains including HeyTea, Haidilao & Chagee take America by storm

THE NEW YORK TIMES: Restaurant and drink brands, some with thousands of stores in China, are taking root in American cities to escape punishing competition at home.

The economic relationship between the United States and China is as fraught as it has been in recent memory, but that has not stopped a wave of Chinese food and beverage chains from moving aggressively into the United States for the first time.

Chinese tea shops in New York and Los Angeles are offering consumers drinks topped with a milk or cheese foam. Fried chicken sandwich joints are trying to lure diners in California with affordable fast food.

Restaurant and drink brands, some with thousands of stores in China, are taking root in American cities to escape punishing competition at home.

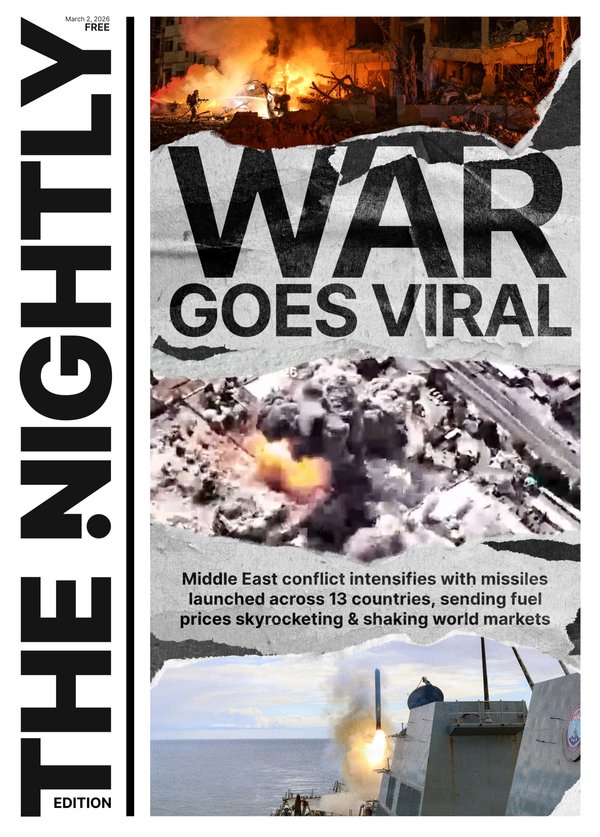

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.HeyTea, a tea chain originating in Jiangmen, a city in southern China, has opened three dozen stores nationwide since 2023, including a flagship operation in Times Square in New York.

Two other rival tea brands, Chagee and Naisnow, opened their first US stores this year. Luckin Coffee, a chain with three outlets for every one Starbucks in China, opened several spots across Manhattan.

Wallace, one of China’s largest fast-food chains with more than 20,000 stores selling fried chicken and hamburgers, landed in Walnut, California, for its first shop.

Haidilao, China’s largest hot-pot chain, is redoubling its efforts in the United States after entering the market more than a decade ago.

The American expansion comes at a challenging moment for China’s food and beverage industry. The Chinese economy is no longer growing at a breakneck pace, hampered by a long-running real estate crisis and sluggish consumer spending.

To survive, restaurant chains are undercutting one another on prices, inciting an unsustainable, profit-killing race to the bottom.

“China’s food service industry is suffering from severe oversupply,” said Bob Qing, the founder of Tomato Capital, a Chinese firm that invests in restaurants.

In China, there are three times more food and beverage establishments per capita than there are in the United States, according to Qing. And half the new restaurants that open in China close within a year.

Many Chinese fast-food restaurants have expanded internationally in recent years, especially in Asia, but the United States, according to Qing, holds significant appeal because it is “the only market as mature and large as China.”

But a US expansion is not without its challenges. Chinese brands must walk a geopolitical tightrope because of China’s position as an economic rival — or adversary — to the United States.

While their global expansion is celebrated in China as a sign of the country’s progress and development, it can be viewed as a threat to America’s local businesses.

Chinese food and beverage chains are moving into the United States as many American brands that stormed into China decades earlier are pulling back.

This month, Starbucks sold a controlling stake in its China operations to a Chinese investment firm, Boyu Capital. The fast-food conglomerate Restaurant Brands International sold most of Burger King’s China business to a Chinese private equity firm.

Domestic competition is especially fierce in China, where milk tea shops have sprouted up over the past decade. According to some estimates, there are 420,000 milk tea shops in China.

Some stores have started selling drinks for less than $1, while others offer free online orders. Many of these brands carry an upscale version of bubble tea, which has been wildly popular for years.

They brew loose tea leaves instead of using tea bags or powder and add fruit slices, fresh milk or whipped cream cheese foam on top.

HeyTea, which helped pioneer the trend and has about 4,000 stores in China, stopped accepting new franchise applications this year. The company started its American expansion two years ago as the battle among tea brands intensified.

At HeyTea’s store in Times Square one recent afternoon, lines stretched out the door with groups of customers waiting for elaborate drink concoctions such as a signature fruit tea topped with cheese foam.

“They are getting so big now,” said Farida Abdelaziz, 20, who waited up to 30 minutes with her friends for drinks.

Naisnow, a smaller Chinese tea brand, opened its first US store in Flushing, a predominantly Asian neighbourhood in New York, in October.

The lines were long and sales were brisk. Its most popular items were avocado and kale-based drinks made for the United States. The company said it aimed to expand to 500 stores over the next three to five years.

Jerry Yao, Naisnow’s deputy manager in charge of overseas development, said one difference was already apparent: “The margins are definitely better than in China.”

The transition to the United States is not always smooth. The hot-pot chain Haidilao, which has a cultlike following in China, struggled when it first entered the market in 2013.

It did not provide English-language menus. The prices were higher than customers had expected. And its trademark over-the-top service came across as intrusive.

In China, Haidilao’s staff provides free manicures to customers waiting for a table, performs noodle-making dances to entertain guests and even peels shrimp by hand for diners.

But the staff’s attentiveness was initially perceived as “eavesdropping” in the United States, said Qu Cong, the chief financial officer of Super Hi International Holdings, Haidilao’s overseas business entity.

“For American customers, there’s a strong sense of boundaries, so simply copying the practices used in China might not work,” Qu said.

Haidilao provided more guidance, in English, on how to navigate the hot-pot dining experience, in which diners dip various raw ingredients into a pot of boiling broth at the table. It tweaked the spice levels on some soup bases and expanded the beef selection.

The chain generated social media buzz over the summer when one of its restaurants appeared in the final episode of “And Just Like That...,” the sequel to “Sex and the City.”

In the episode, the hostess sees that Carrie Bradshaw is dining alone and brings out “Tommy Tomato,” a plush doll, to fill the empty seat.

Chinese brands must weigh how much to cater to local tastes. When Wallace, a fast-food chain, opened its first US store last year, it stripped down its sprawling menu to focus mainly on fried chicken sandwiches.

Ricky Chen, the president of Wallace USA, said the standard chicken sandwich the company served in China came with lettuce and mayonnaise.

For American diners, Wallace removed the lettuce and added a pickle, which is something Chinese customers “don’t really eat.” It also made its food saltier.

Chen likes Wallace’s chances in the new market. “American fast food is getting too expensive,” he said. At its location in California, Wallace offers three full-size chicken sandwiches for $10. By comparison, a single chicken sandwich at Chick-fil-A or KFC sells for about $6.

Wallace does not hide its Chinese roots, Chen said. But it also does not promote them. At first, most of his customers were Asian because they were familiar with the brand. That has since changed.

Wallace said it planned to open 10 more locations by the end of 2026.

Chagee, a tea brand that started selling shares on the Nasdaq stock exchange in May, said customers did not perceive it as a Chinese brand. It derives its name from an ancient Chinese love story.

Its logo features a concubine in a Beijing Opera costume, faintly resembling the Starbucks two-tailed mermaid logo.

Emily Chang, Chagee’s chief commercial officer in North America, said she was hired to develop the company as an ABC, or American-born Chinese, brand.

She said that it had more than a dozen stores “in the pipeline” and that it planned to move beyond California. Chagee started in Los Angeles in April.

Qing, the restaurant investor and consultant, said that despite geopolitical tensions, the United States had welcomed China’s food and drink brands. He said the US Embassy in Beijing invited him and chain restaurant owners to tour various American cities earlier this year.

“This is one of the few industries in which people are still willing to engage in that kind of exchange,” he said.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

© 2025 The New York Times Company

Originally published on The New York Times