Nick Bruining: Death, superannuation and who can get their hands on what and when

There’s a lot of rules around super and what happens to your savings when you die. It can get even more complicated when someone is acting on your behalf. Here’s your guide to avoid a payout delay.

One of the big issues that arises on the death of a partner is the need to make changes to the death benefit nomination of a superannuation fund.

That can become problematic if the surviving partner has lost “capacity” — perhaps through dementia or some other medical condition.

Under superannuation laws, a super fund can only pay a death benefit to a dependant of the deceased or the estate of the deceased, often referred to as the legal personal representative, or LPR. It usually cannot make a payment to anyone else including siblings, parents, charities or best mates.

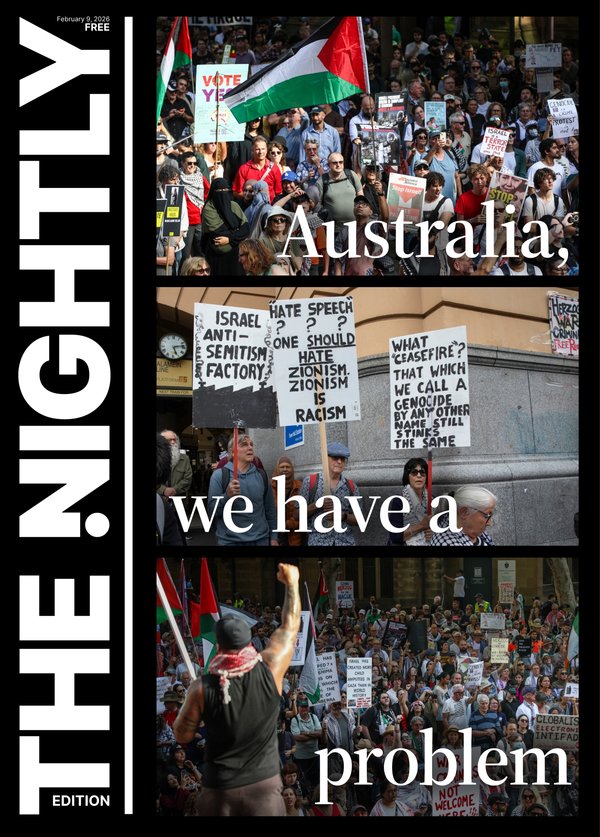

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.A non-lapsing binding death benefit nomination is regarded as the Rolls-Royce document that instructs the super fund which dependants the money is to be paid to.

When the money is paid to a dependant that is not a financial dependant, tax is payable on the taxable portion of the fund, which in most cases is the bulk of any death benefit payment.

Usually, offsets and rebates reduce the tax payable to 15 per cent plus the Medicare levy. The gross amount of the payment can upset income-tested government benefits such as paid parental leave, family tax benefits and even extra superannuation contributions tax.

Financial dependants — which would include the spouse or partner and possibly under-age children still living at home — pay no tax on a death benefit payment.

For that reason, financial planners generally recommend that when there are no “tax-free” financial dependants left, the death benefit nomination should be changed to direct that the death benefit is paid to the estate. While the 15 per cent tax is still payable, there’s no Medicare levy and distributions from an estate generally don’t form part of a beneficiary’s assessable income.

When the surviving partner who receives a deceased person’s death benefit still has their wits about them, making a change to the death benefit nomination form is a relatively simple process.

Download the form from the super fund’s website, fill in the details, sign and have it witnessed and send it back to the super fund. Job done.

And thanks to a Queensland Supreme Court decision dating back to 2018 known as the Giles case, most super funds are now happy to accept changes made by a properly authorised attorney, set up through an EPA.

In 2013, Mr Giles lost capacity and his spouse and sister signed a lapsing binding death nomination. This type of nomination is slightly inferior to the non-lapsing variety because it needs renewing every three years.

Without detailing the nitty-gritty of the case, the court allowed the re-signed nomination to stand while making some important points.

These included the issue of conflicts of interest.

An EPA used to change the death benefit nomination that might depart from the original intentions of the super fund member might land the attorney in hot water. For example, if all the kids are nominated in an original death benefit nomination form and an EPA is used to change the payment to just one child, that could be seen as a conflict of interest.

One final point to note.

Most of the large Australian Prudential Regulation Authority-regulated super funds have standing policies in place. When a single nominated death benefit recipient is no longer with us, the default position is to pay the proceeds to the estate.

While that means the end result is the same as a changed nomination form directing the proceeds to be paid to the estate, there could be significant delays in processing the payment because the super fund, by law, will need to make extensive enquiries.

This can sometimes delay the payout by months.

Nick Bruining is an independent financial adviser and a member of the Certified Independent Financial Advisers Association.

Originally published on The West Australian