The Economist: How to tax billionaires—and how not to

It is easy to understand why the world’s non-multimillionaires may want to soak the very rich.

The rich are different from other people. They have more money and, in most places, they pay much less tax.

Going by one broad definition of income that combines consumption and someone’s change in net worth, America’s best-heeled pay just a few cents on every dollar of their fortunes.

Lately, those fortunes have ballooned thanks to a soaring stockmarket.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.One study found that unrealised capital gains account for $6trn of the $11trn in wealth held by the richest Americans.

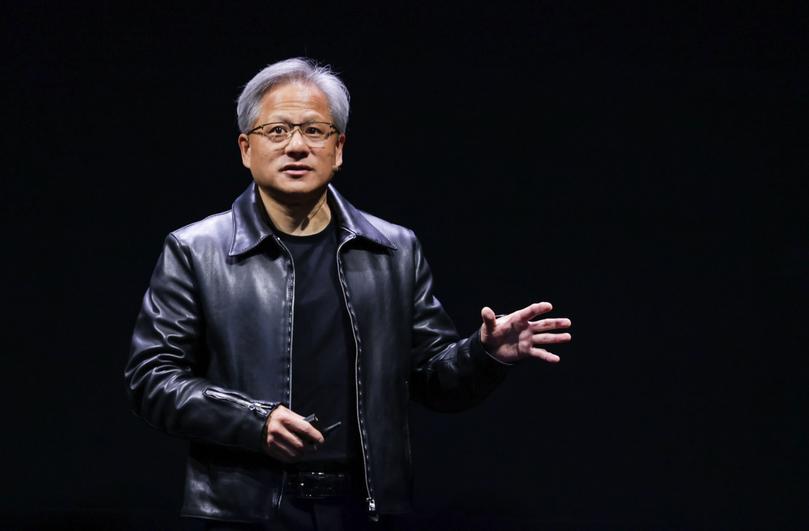

Since 2023, as the artificial-intelligence frenzy has fuelled demand for both Nvidia’s GPUs and also its shares, the chipmaker’s founder, Jensen Huang, made more than $100bn.

But until he sells some of his stocks, the money is off-limits to the taxman.

Cash-strapped governments want to get their hands on a slice of these riches.

Next year Australia will start taxing unrealised gains in employee pension-fund accounts with balances of more than A$3m ($2m).

As part of his re-election campaign, President Joe Biden is promising to find $500bn over ten years for social programs by charging a 25 per cent tax on the unrealised capital gains of individuals who, like Mr Huang and 10,000 other Americans, are worth $100m or more.

It is easy to understand why the world’s non-multimillionaires may want to soak the very rich.

It is equally easy to grasp the appeal for governments, which the wealthy are playing for fools by coming up with clever ways to live in the lap of luxury without ever realising any capital gains.

One of these manoeuvres is to buy assets, offer these as collateral for loans and roll over the loans until they die.

At that point any capital gains accrued over the owner’s lifetime are zeroed out and the clock starts anew for their heirs, who then themselves “buy, borrow and die”, as this (perfectly legal) device is known.

However, taxing unrealised gains is complex and wrongheaded. It is also unnecessary. A similar end could be met with much less controversial means.

Taxes should be simple to administer and collect.

Ideally, they should also raise revenue while distorting behaviour as little as possible.

Taxing unrealised gains fails on each of these counts.

Calculating someone’s net worth is nightmarishly complicated even once, at their death, let alone every year.

America’s Internal Revenue Service took 12 years to put a value on Michael Jackson’s estate.

France, Sweden and a few other European countries that have tried to levy wealth taxes have abandoned their efforts after generating lots of administrative headaches but little actual revenue.

Taxing unrealised gains would also cause wild swings in the liabilities of people who own volatile assets, such as Mr Huang and his Nvidia shares.

Mr Biden’s proposal, which assesses the tax over five years, smoothes out some of this volatility.

But some taxpayers will still fail to get a rebate for their unrealised losses.

That could discourage angel investors and other serial risk-takers from backing promising ventures whose stratospheric valuations could suddenly collapse, and which can be hard to price.

And, in America, taxing unrealised gains may be unconstitutional.

Any day now the Supreme Court will rule in a case in which the plaintiffs claim that a one-off levy on foreign investments in 2017 was illegal because it taxed their unrealised gains.

Even if the justices issue a narrow ruling that leaves the principle intact, Mr Biden’s idea will be challenged.

What, then, are the tax authorities to do?

In America, they could start by ending the rule that lets inheritors reset the clock for capital-gains each time someone dies.

This provision of the tax code, called “step-up in basis”, was introduced in 1921, five years after estate taxes, which are assessed on the market value of assets at the owner’s death.

The goal was to avoid double taxation. If heirs paid estate tax on this fair value, they should not also pay tax on any further capital gains.

This rationale looks flimsy now that the biggest estates are built not on earned income, which would have been taxed throughout an estate-builder’s life, but on assets’ appreciation, which was not.

Heirs who get rich thanks to their benefactor’s “buy, borrow, die” are therefore treated very differently from those who inherited a fortune by amassing taxed income.

Scrapping step-up in basis could yield perhaps a quarter of the $500bn, or 2 per cent of GDP, that Mr Biden hopes to get from his wealth tax, at a far lower administrative cost.

Taxing capital gains at death would raise the same again.

He could realise much of the rest by closing other loopholes, notably the “carried interest” provision which lets buyout barons pay capital-gains tax rather than (typically higher) income tax on their private-equity firms’ investment profits.

Going after unrealised gains is easy to understand and therefore good politics. But it is bad economics.