Wicked the books: Before it was a musical, the smash hit was a political allegory about fascism and populism

Eight years before Wicked debuted on stage, it was a novel that reframed The Wicked Witch of the West as an activist fighting against fascism and populism.

It’s the season of the witch. Wicked fever is about to take over when the screen adaptation of the Broadway musical is released in two and a half weeks.

For fans of the musical, it’s the realisation of a long-held dream. At the Australian premiere of the film in Sydney last night, attendees in the queue could be heard comparing notes on how many times they’ve seen it on stage. Six times, one proclaimed, only to be gazumped by their friend — 12 times!

The stage production debuted in San Francisco in 2003, before going on to play Broadway, the West End and all over the world including here when it first graced Melbourne’s Regent Theatre in 2008 and had several seasons across Australia since then.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Wicked is an ambitious, buoyant and emotionally charged production with earworm belters and big feelings. It’s not surprising that since its debut 21 years ago, it has well passed the $US1 billion mark in ticket sales.

Devotees know the songs word-by-word and they could name every iteration of the Broadway cast, especially the two women who originated the roles – Idina Menzel and Kristin Chenoweth. So, a movie version they could watch over and over without shelling out for $200 tickets?

Well, that’s just a little bit exciting, isn’t it?

Unless you’ve been deliberately ignoring the hype (perhaps Andrew Lloyd Webber’s trenchant sentimentalism has scared you off musicals for life, and who could blame you), you’re probably familiar with the general story of Wicked.

It is based on The Wicked Witch of the West from The Wizard of Oz, but it reclaims her story so that she is the hero and not the villain.

Born green and ostracised by her family, her classmates and then everyone, she is given depth, a backstory and a name — Elphaba, which is formed from the initials of L. Frank Baum, who wrote the Oz books, themselves a barely veiled critique of US President William McKinley.

She is not just the cackling Big Bad Witch that must be tamed by a clueless visitor in a gingham dress and shiny shoes. She is a woman with a strong sense of social justice who also falls in love with a prince.

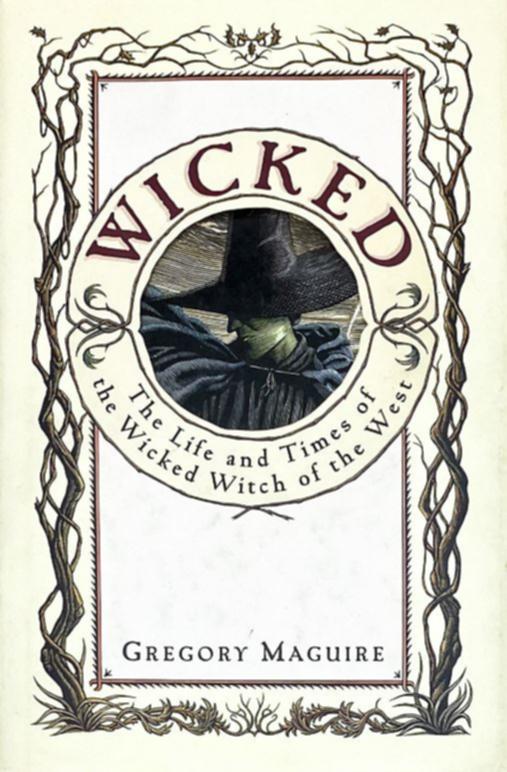

What many casual observers — and even some fans — may not realise is that Wicked is not a direct revisionist story of The Wizard of Oz. It is, in fact, based on a book by Gregory Maguire, published in 1995, and then followed up with three sequels — Son of a Witch, A Lion Among Men and Out of Oz.

While the stage production and the film re-focuses the story of the friendship between Elphaba (Cynthia Erivo) and Galinda (Ariana Grande), and the love story between Elphaba and Fiyero (Jonathan Bailey), Maguire’s book is a political and philosophical allegory, interested in how fascism, populism, propaganda and power works and is weaponised against those who are different or disagree.

The book is a fantastic read. It’s searing and smart, and grapples with heavyweight themes but packaged in a story that draws on familiar characters and tropes. By taking the stock character of the green witch in the pointy hat who is universally perceived to be “evil”, Maguire is challenging the reader to reconsider the myths we take as truth.

Maguire has always said the germ of the idea came out of the James Bulger murder in 1993 in which two 10-year-old boys, Robert Thompson and Jon Venables, kidnapped, tortured and killed a two-year-old toddler. Unable to comprehend how two offenders that young could commit such a crime, the label “evil” was thrown around, as if that could somehow explain something so inexplicable.

Not long before that had been the first Gulf War against Saddam Hussein, which also prompted Maguire to think about how words and labels are deployed to dehumanise people. Words like “wicked”.

In the novel, the main thrust of the story is not Elphaba’s friendship with Galinda or how romance with Fiyero, it is her political activism. The musical and the film touch on it but it’s a much bigger deal in the book, it’s sparked when she discovers that Animals (sentient animals who speak and are part of Oz society) are being pushed out and locked up.

The wizard is an empty shirt, a mediocre man with no real gifts or talents other than to manipulate and divide. In Maguire’s more textured story, Elphaba goes underground for several years to work against the Wizard’s forces, committing what one side could call “terrorism” in a similar way that Star Wars Rebels could fall under the same label.

The musical is its own thing and, tonally, it’s a very different proposition. It whisks audiences into a fantasy world and while it has an overarching, humanist (forgive us, book Elphaba actually hates the word humanist) message of resistance against hate, it’s not the primary thing.

You’ll get a much richer and complex experience of these ideas through Maguire’s pages.

Writing in 1995, Maguire evoked the fascist regimes of the past, led by monstrous men who exploited suspicions against the “other” to consolidate their power and control. But it’s not so “in the past” now.

In an interview with Broadway World in 2020, Maguire said, “The moral question that the play and the book ask became more urgent since the day that it was published in 1995.

“The world has become more dangerous and despotism has become more apparent, not just in the Middle East but in Europe, and our own Western Hemisphere as well. And so, it shocks me and saddens me that I think the story is more urgent now than it was 25 years ago. But I think it is.”