Could Bluey be a victim of Donald Trump’s tariffs?

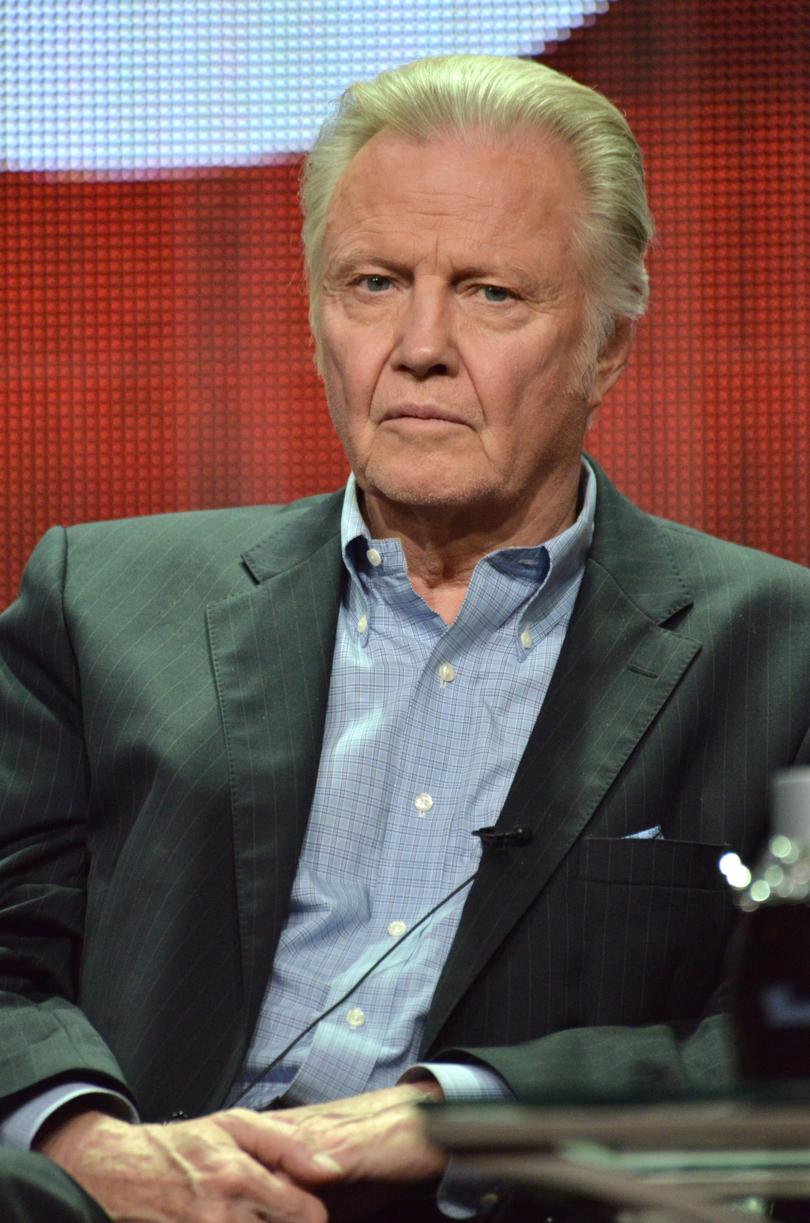

Three days after Donald Trump announced a tariff against movies, could actor Jon Voight’s proposal to ‘make Hollywood great again’ shed any light on how things will shake out?

There are fears one of Australia’s most popular exports Bluey could be hit by Donald Trump’s undefined movie tariffs.

Three days after Mr Trump’s blockbuster announcement that he would impose a 100 per cent tariff on all movies produced outside of the US, confusion still reigns as to what will be legislated and how any of it would work.

Overnight, Australia’s ambassador to the US, Kevin Rudd weighed in saying “I don’t think we want to see a tax on Bluey”.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.The Australian animated series is beloved in the US, and was in 2024 the most watched series by time spent (more than 20 billion minutes) across all streaming platforms in America.

The show comes from Australian production studio Ludo, and is made in Brisbane. Ludo is working with Disney and the BBC on a full-length feature film for cinema release in 2027.

As a co-production between Australia, the UK and the US, the Bluey movie speaks to the interconnectedness of the global entertainment industry, and the logistical challenges of instituting a tariff scheme that is, purportedly, designed to reinvigorate the American screen sector.

After the initial social media post from Mr Trump implying a blanket tariff, White House spokesperson Kush Desai appeared to walk the president’s comments back, saying “no final decisions” had been made.

“The administration is exploring all options to deliver on President Trump’s directive to safeguard our country’s national and economic security while making Hollywood great again,” he said.

In the days since American studio bosses have been jostling for facetime with the Trump administration, and governments around the world are considering what it might mean for their local screen industry.

In the 2023-24 financial year, international film and TV productions spent $767 million in Australia, down from $1.2 billion the year before, according to Screen Australia. The decline is at least partly attributed to 2023 Hollywood strikes which impacted the volume of productions.

Foreign Minister Penny Wong said collaboration between the US and Australia is good for both countries. “Audiences in the US as well as in Australia like to see Australian actors. We know American films are also filmed here in Australia. You know, The Fall Guy, the Elvis film. So, the reality is that the industry is set up where we do cooperate together,” she said.

“We certainly will be engaging not just for the economic opportunity, which you point out, it’s a big, big earner for Australia, but also because it’s a good thing for us to be working together on films, and on entertainment.”

This week’s tariff announcement, as vague as it was, has it roots in Mr Trump’s January appointment of actors Jon Voight, Sylvester Stallone and Mel Gibson as his envoys in Hollywood. At the time, few took it seriously. Gibson said he found out about it on the news.

Voight certainly answered the call. He spent the weekend with Mr Trump at Mar-a-Lago in Florida, and while the proposal put forward by him was more detailed and nuanced, it did contain the word “tariffs”, albeit in a specific circumstance.

Likely, Mr Trump, who once declared “tariffs” as the “most beautiful word to me in the dictionary”, heard it and ran with it, in line with his approach to shoot first and ask questions later.

Mr Trump has since said he doesn’t want to “hurt” the industry and that his team will meet with Hollywood leaders to keep them “happy”.

So, what was in Voight’s proposal? The five-page document had been circulated around the industry and was leaked to Deadline, which published it in full. While Mr Trump only mentioned movies, Voight’s proposal includes all theatrical, broadcast, cable and streaming productions, specifically mentioning the likes of Netflix, Apple and Amazon.

Streamers, especially Netflix, have global operations and produce programming in many countries, some of which fall under content obligations set out by other nations to protect their cultural output.

While Voight and Mr Trump have called other countries’ requirements as an uneven playing field, many of them were established to ensure that those smaller markets were protected by being overwhelmed by the US’s cultural soft power.

The US entertainment industry is dominant globally and according to a Motion Picture Association report, in 2022, the American sector produced a $US15.3 billion trade surplus, meaning the US made more money from the rest of the world than vice versa.

Voight’s proposal was generally focused more on carrots than the stick, making the case for increased state and federal tax incentives for US-made productions, inducement for theatre owners to upgrade facilities, increased job training, shifting ownership of content from streamers and broadcast networks to producers and creators, and uncapping tax incentives in California.

The part that refers specifically to tariffs is a proposal that if a US-based production chooses to shoot or make that title overseas, a tariff of 120 per cent should be placed on the amount equal to any foreign incentives that production receives.

The Australian federal government offers a 30 per cent tax offset, on top of state incentives, for productions that spend more than $15 million in the country. For example, The Fall Guy starring Ryan Gosling, received almost $45 million from the Australian and NSW governments. Under Voight’s tariff proposal, that amount would be tariffed at 120 per cent by the US government.

Voight has also floated the idea of “treaties” between the US and other countries for co-productions that would qualify for US incentives and be exempt from “the excise tax”. He suggested the first treaty should be negotiated with the UK and then be used as a template for other countries.

The US screen production industry has suffered a downturn as it loses projects to countries including Australia, the UK, Canada and New Zealand which offer not just financial incentives but also experienced crew and talent at lower rates. The US guilds keep wages high, adding to the cost of shooting in the US.

FilmLA estimated that production in Los Angeles has declined by 40 per cent in the past decade. In the first three months of this year, it is already down 22 per cent, in large part due to the wildfires that burnt throughout the city in January.

LA has also lost productions to other US states including Georgia where there are large hubs in Atlanta. Many in the industry agree it’s a problem, even if they’re not onboard with Mr Trump’s tariffs threat. The guilds including the Directors Guild of America and IATSE, which looks after technicians and craftspeople, have lobbied for increased protections.

Voight told Variety, “It’s come to a point where we really do need help, and thank god the president cares about Hollywood and movies. He has a great love for Hollywood in that way. We’ve got to roll up our sleeves here. We can’t let it go down the drain like Detroit.”

While everyone waits to see how Mr Trump’s latest tariffs play shakes out, Mr Rudd makes the point that one of the great benefits of the free flow of films, streaming and TV programs around the world is that exposure to different kinds of stories create empathy and curiosity about other cultures.

He said, “What happens if we al lock down our countries with competitive, punitive arrangements against each other’s movies? Movies are the way in which we kind of understand each other more. So, I’d be all for opening this up.”