WENLEI MA: Please stop watching things with subtitles on

WENLEI MA: Unless you have accessibility issues or it’s a non-English language project, please stop watching TV shows and movies with the subtitles on. The madness must stop.

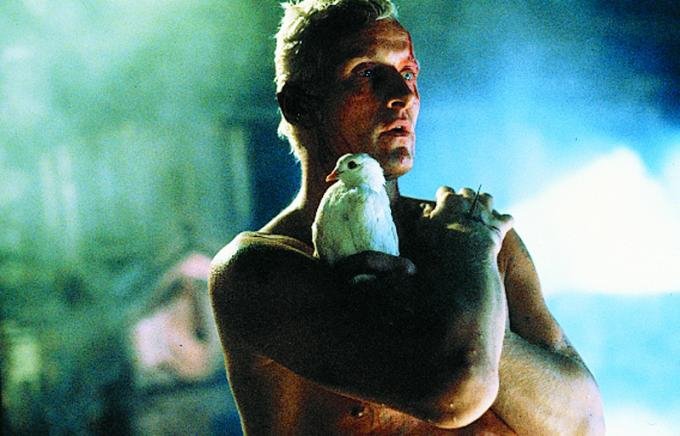

The 11-piece orchestra was positioned on stage, surrounded by neon lights with a large screen above them. Almost 9,000 people were taking their seats, settling in for one of cinema’s greatest stories: Blade Runner.

Ridley Scott’s sci-fi masterpiece was to be screened with a live orchestra accompaniment, and for the experience, I’d shelled out $149 for my seat. The movie started to play and at the first line of dialogue, subtitles came up.

English subtitles for an English-language film playing in an English-speaking country. I was enraged. It really hit a nerve. I want a refund.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Subtitles is the petty hill I will die on.

The fact the subtitles scourge was expanding to a public arena, beyond the personal choice of home entertainment, ran through me like a ghostly chill. What if this becomes the norm? What if every cinema session had mandatory subtitles just because young people can’t seem to watch anything without reading it at the same time?

I know just saying “young people” tags me as an old person yelling at clouds, but, for me, it represents all that is unholy about how people watch things in 2024. Not with an appreciation for the art, craft and vision of the filmmaker or storyteller but with their half-arsed attention while scrolling through TikTok.

I want to acknowledge, if you need subtitles for accessibility reasons, obviously that’s what they’re for, and I’m aware of the privilege of not needing subtitles because I don’t have accessibility issues. That’s not my beef. Nor is subtitles for non-English language TV shows or films, because the alternatives – not watching them or, god forbid, a dubbing track – is way worse.

Research released this week by American company Talker found 30 per cent of Gen Z-ers say they “always” watch with subtitles on. And anecdotally, I know loads of 20-somethings who do. They’re also watching mostly on laptops and mobile phones, which makes both me and Christopher Nolan want to crawl into a hole.

Sometimes there are practicalities involved – maybe you’re trying to not disturb someone sleeping or when I was a kid, when my baby brother’s screams reverberated through the whole house, I remember watching Xena, Warrior Princess with closed captions that sometimes threw up descriptors like “horse neighs”.

And I will concede that streaming technology has led to a kind of compression and flattening of audio tracks for home entertainment so that in some instances, it is legitimately harder to hear some dialogue over the ambient soundtrack. But most titles don’t feature Tom Hardy muttering behind a Bane mask.

So, “always” instead of as a last resort? That’s wild. It’s defeatist.

Films and TV shows are made of a thousand deliberate choices. Each frame chosen for its visual impact, for an actor’s performance. Every sound effect, bar of a composition, line of dialogue adds up to a whole.

It definitely doesn’t add up to occasionally glancing up from your phone to watch the bottom fourth of the screen to try and figure out what’s been going on. Or having crucial dramatic moments spoiled because the subtitles are ahead of the spoken dialogue.

That terrible Blade Runner Live experience (the screen was also tiny, the whole thing was a rip-off, highly not recommended) was ruined by the presence of the intrusive subtitles not only pre-empting what the characters were about to say, creating a second conversation in my head, it was also a blight on cinematographer Jordan Cronenweth’s striking visuals. Tears in the rain? Forget about it, read this instead.

People flick through online videos with brutal efficiency, giving it four seconds before dispatching it for the next. With the battle for attention, it can feel an impossible ask that someone focus on just one thing for an entire two-hour movie, or even a 27-minute episode of a streaming comedy.

An American psychologist, Dr Gloria Mark from the University of California, Irvine, found in a 2004 study that participants on average kept their attention on a screen for two-and-a-half- minutes. By 2012, it had fallen to one-minute-and-25-seconds. Now, it’s 47 seconds.

It’s grim and some of it will rely on tech companies to play ball and figure out a way to deliver crisper dialogue tracks. Or for algorithms to stop prioritising and serving up bite-sized “content”. It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy.

But for some, especially Zoomers who have self-conditioned to always have subtitles on, it’s not because they can’t hear it, it’s because they’re not willing to. It’s going to take something else for those recalcitrant hold-outs to experience a TV series or film the way it’s meant to be: Stop being distracted and pay attention.

Before we’re all doomed to suffer through subtitles in public.