JOHN McDONALD: Bangkok Art Biennale explores deep themes on an earth under attack

JOHN McDONALD: From Beethoven being conducted to a hearing-impaired choir to swimming with tigers in high heels - there’s no shortage of artistic ambition in the environmentally-minded Bangkok Art Biennale.

When the British scientist, James Lovelock, published his book, Gaia: A New Look at Life on Earth in 1979, it quickly became a best-seller. Lovelock’s thesis was an attractive one, suggesting that the planet and its countless organisms worked together in a process of co-evolution. It was roughly the same conception of the world found in Plato’s Timaeus, now bolstered with modern scientific authority.

Because Lovelock’s view overturned Darwin’s ideas about the survival of the fittest, the thesis was vigorously disputed by thinkers such as Richard Dawkins and Stephen Jay Gould. Over the past 40 years that debate has never ceased, but while the scientists may remain unconvinced, Gaia, named after the Greek goddess of the earth, has enjoyed a huge popular success. True or false, the idea of the planet as a self-sustaining organism has been taken up by environmentalists who see global warming as a danger to this natural order.

It’s an idea that holds a special fascination for artists, who have never shied away from overarching cosmic theories, or magical or Utopian thinking. Being an artist means having a licence to dream, and a willingness to explore creative responses to intractable problems.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.For its fourth instalment, the Bangkok Art Biennale has adopted the theme, Nurturing Gaia. As might be expected, there is an emphasis on the environment, but also a much broader understanding of sustainability, looking at what it takes to live together in an increasingly fractured world. In line with the ‘mother earth’ motif, it’s a powerfully feminine show, even though male contributors are slightly in the majority. Featuring 76 artists or groups of artists, from 39 countries, the show confirms Thailand as a rising force in international contemporary art.

The BAB was launched in 2018, by Apinan Poshyananda – artist, curator, art historian - the best-connected figure in the Thai art world. As director and CEO, Poshyananda leads from the front, happy to explain his ideas and pick out highlights as the press visited eleven venues over two days. If you’re familiar with the traffic in Bangkok, you’ll recognise this as a heroic effort.

Most biennales change creative directors from one show to the next, but the continuous involvement of one uber director makes good sense. It ensures consistency and removes the problem of each new curator having to learn everything from scratch. A wholly benevolent dictator, Poshyananda employs a seven-person advisory committee, and a team of four curators who select both Thai and international artists. This year, the curators were Pojal Akratanakul and Paramaporn Sirkulchayanont from Thailand; Akiko Miki, from the Benesse Art Site, Japan; and Irishman, Brian Curtin, who lives and teaches in Bangkok.

As usual, the show includes a few big names, both living and dead. The posthumous headliners are Louise Bourgeois and Joseph Beuys, and the best-known contemporary artists are Anish Kapoor and Tony Cragg, both represented by new public artworks at One Bangkok, a towering development that will include luxury apartments, five-star hotels, high-end retail and a central entertainment arena.

The works by Cragg and Kapoor are placed on the edges of this central plaza – two shiny, stainless-steel creations: the former a large, abstracted figure, seemingly captured in motion; the latter, a long, curved mirror-wall that flips the viewer’s reflection upside down. The artists have made many variations on these themes, and the new works are essentially trophies, signifying Bangkok’s membership of an élite group of world cities that possess such glittering baubles. Perhaps the National Gallery of Australia thinks Lindy Lee’s shiny new sculpture will put Canberra in this category – the only difference being that Cragg and Kapoor are global brands, Lee a local product.

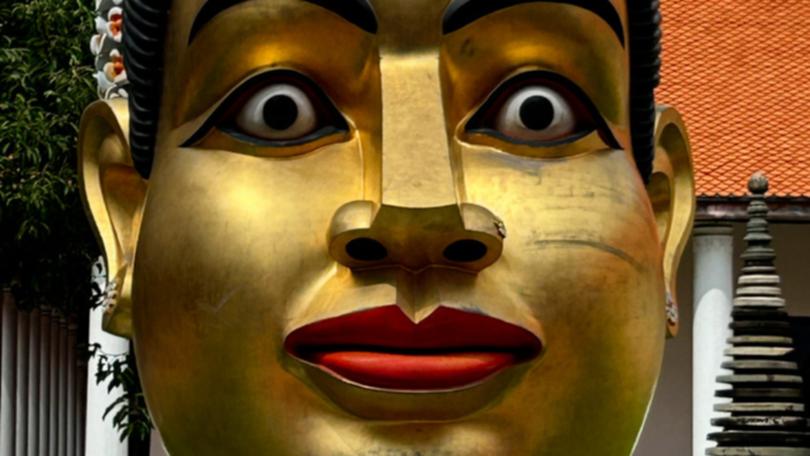

One of the unique features of the BAB is the installation of artworks in the grounds of Buddhist temple complexes. This required long and delicate negotiations when first suggested in 2018, but today there are four temples participating - Wat Pho, Wat Arun, Wat Prayoon and Wat Bowon. For the most part, the offerings are modest, being overshadowed by the temples themselves, with spectacles such as the gigantic Reclining Buddha, in Wat Pho.

The standout work among the temples is Jessica Segall’s (un)common intimacy, at Wat Prayoon, a two-channel video installation showing the artist in a red swimsuit with white polka dots – and, believe-it-or-not, red high heeled shoes - swimming with a tiger, then with a crocodile. It takes a minute or two to get a grip on what we’re seeing. Is it real? Is it done with props? AI?

It’s all real, shot in a tank of water in Florida, where people are apparently allowed to keep large predators as pets (no Trump jokes, please). Segall, a New Yorker who believes humans are more dangerous than these creatures, jumped fearlessly into the pool with them to prove her point. It’s mesmerising to see her exchanging touches with the tiger’s paw or caressing the croc’s scaley flanks. She emerged with only a few scratches, having achieved the most extreme interspecies communion since David Attenborough huddled with a family of gorillas in the forests of Rwanda.

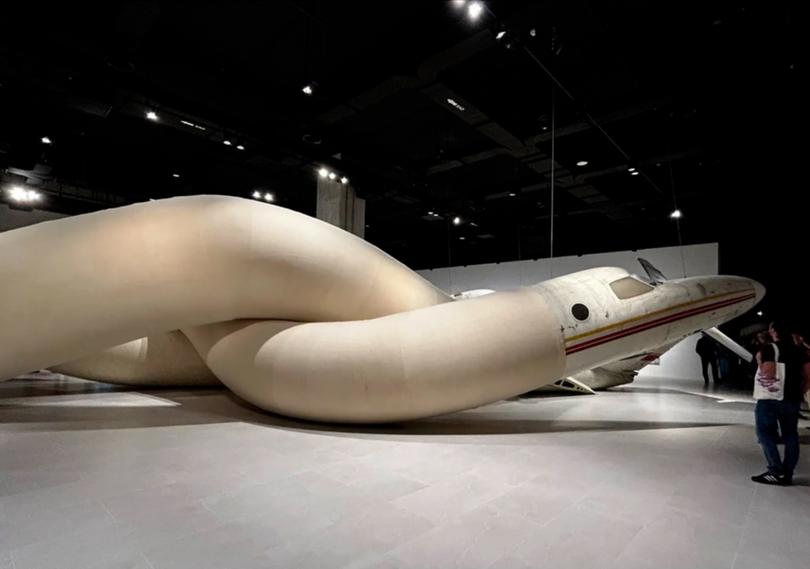

The largest section of the Biennale was to be found at the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre, with another substantial component at the Queen Sirikit National Convention Centre – a building so vast and empty that the entire exhibition could have been housed within its walls with room to spare. It was, however, the only venue big enough to house Adel Abdessemed’s Like Mother, Like Son - an installation composed of three jet airplanes that twist and curl like serpents.

One surprise this year was the number of Irish artists, no doubt courtesy of curator, Brian Curtin. Among a lively group of works, Amanda Coogan gets points for difficulty, in conducting a version of Beethoven’s Ninth (Ode to Joy), with a “silent choir” of Thais with hearing disabilities. Beethoven may have been deaf when he composed the work, but he didn’t have to communicate with a mixture of Irish and Thai signing, in front of a huge hoarding covered in secondhand clothes.

As a symbol of Gaia in action, I was struck by an image by Japanese artist, AKI INOMATA (she prefers all caps), who showed footage of an octopus crawling inside a glass model of an extinct ammonite. It suggested both the continuity of life, and a belief that history acts as our defence against present-day dangers.

I’m only able to scrape the surface of this sprawling exhibition, but the two most absorbing parts of the show were those at the National Museum and the National Gallery. In these venues, being used by the Biennale for the first time, the curators were able to make connections between contemporary works and aftefacts from the permanent collections, putting sexually charged sculptures by Louise Bourgeois alongside two lingas from Kerala, basically phalluses with legs.

At the National Gallery, Aideen Barry contributed another musically themed video, combining Inuit throat singing with the Irish harp, in a strange electropop anthem that took its inspiration from a decree by Queen Elizabeth I in 1603, that all Irish harpists should be hanged and their instruments burned. It says a lot about the globalisation of art that one can travel to Thailand to see a collaborative video between the Irish and the Inuits about a dark moment in history.

George K. from India, filled a gallery with life-sized sculptures of transgendered figures, a group that suffers from extreme social marginalisation, although these people were drawn from a festival in Tamil Nadu. In an adjoining room, Agnes Arellano from the Philippines exhibited four fantastic figures of goddesses, as part of a series based on the Pleiades, or ‘the Seven Sisters’.

The vivid nature of these works, along with a huge outdoor installation by Thai artist, WISHULADA, in which plastic waste has been artfully transfomed into a multi-limbed melée of entwined figures, lent a strong sense of theatricality to the National Gallery presentations.

It was a carnavalesque response to a theme that could so easily have become a didactic exercise in environmental consciousness-raising. It showed that it’s possible to make works about important subjects that provoke delight and curiosity, not guilt or despair.

Maybe the age-old balance of life on earth is under imminent threat, but in Bangkok, in this up-beat Biennale, the roar of life goes on.

John McDonald few to Thailand courtesy of the Bangkok Art Biennale

Bangkok Art Biennale 2024: Nurture Gaia

Multiple venues, Bangkok

Until 25 February 2025