JOHN McDONALD: René Magritte, the artist whose iconic bowler hat and apple images permeated the 20th century

JOHN McDONALD: Australia’s best-known art critic explores the stunning surrealist world of René Magritte.

In Paris in the 1980s, I saw a show called Magritte and Advertising. The first part looked at the huge variety of commercial tasks by which the artist made a living when his paintings weren’t selling. Some of these, notably a brochure for the furrier, Samuel, were covert acts of Surrealism, but most were in the popular styles of the day, demonstrating Magritte’s proficiency and versatility.

The second part brought together a bewildering variety of posters, dust jackets, record covers, and advertisements selling everything from beer to air travel to toilet paper. Repeat that show today, and the possible exhibits would be in the thousands, maybe the tens of thousands. René Magritte (1898-1967), who only became successful in his later years, would have a gigantic income merely from copyright payments.

This posthumous bonanza may explain why the Art Gallery of NSW has chosen to publish a catalogue of arguably the greatest image-maker of the 20th century with a cover divided between a generic sky and an opaque patch of red. It would have been a simple matter to select an appropriate image from more than a hundred works by Magritte, but they probably didn’t want to pay for it. If I’m wrong and it was just a design decision, it was a very poor decision indeed.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

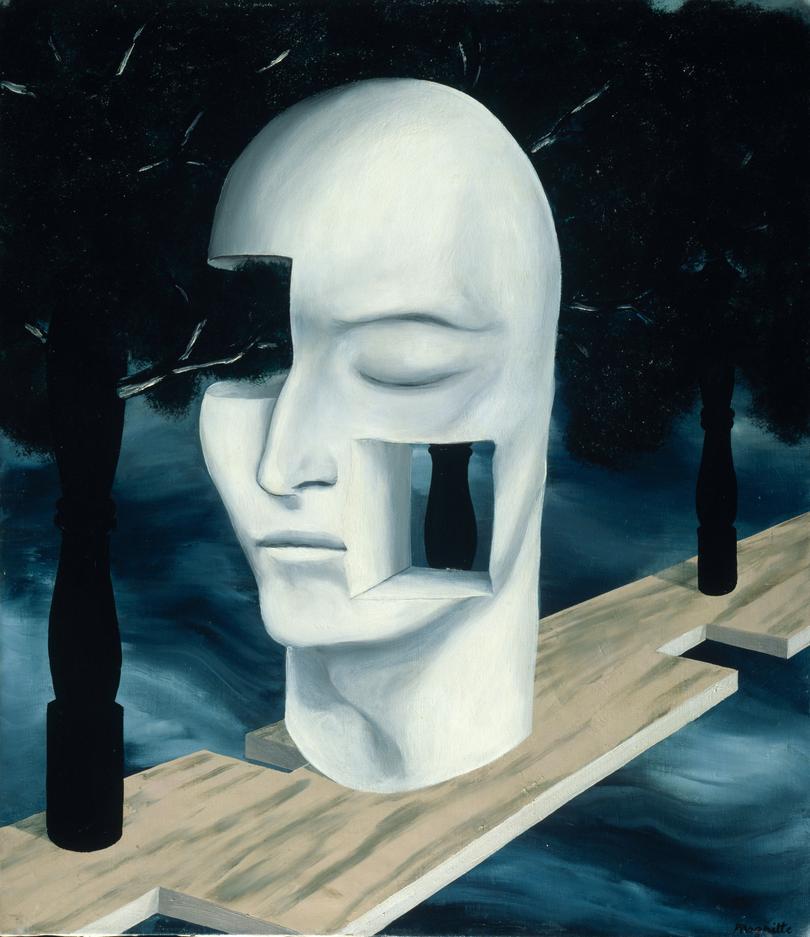

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.As for the show itself, curator, Nick Chambers has assembled a highly respectable group of works, including such iconic pictures as The false mirror(1929) - an eye filled with the sky; The eternally obvious (1930) – a woman’s nude body depicted on five small, framed canvases, arranged vertically; The listening room (1952) - an apple that fills an entire room; Golconda (1953) - men in bowler hats falling like rain; and The dominion of light (1954) – nighttime on the ground, beneath a bright blue sky.

These paintings – or images – will be familiar to many viewers. Where an important work wasn’t available, such as The treachery of images (1929) – better known as This is not a pipe, there is a drawing on the same theme. So too with The red model (1943) – the shoes with human toes.

Happily, Magritte made numerous variations on his favourite motifs. The apple in the room is famous, but he filled another room with a rose and yet another with a stone. There are multiple pictures featuring a painted landscape on an easel in front of a window, through which we see the real landscape; or a broken window that retains the image of the outside world.

The show pays particular attention to Magritte’s early work, which is often overlooked, and to his commercial art. What we see is a young artist trying his hand at every avant-garde tendency he stumbles across, notably Cubism and Futurism. It’s not great art but it’s fascinating to see these experiments in proximity to his mature paintings – if the word “mature” could ever be applied to Magritte. The amateurish nature of these pictures only serves to highlight the slick professionalism of his advertising work.

Magritte has gradually become one of most reliable drawcards for museums around the world, and the AGNSW must be hoping for some big attendance numbers. Aside from Paris, I’ve seen surveys in New York, Frankfurt and London. The Magritte Museum in Brussels, which opened in 2009, has become one of Belgium’s leading tourist attractions.

Magritte’s art has permeated the public consciousness to such an extent that one would have to live in a cave in the wilderness not to encounter some reference on a regular basis. His lifelong aim was to find the extraordinary in the ordinary, but he may have achieved the opposite. In an age of AI and Computer-Generated Imagery, his pictures are no longer as bizarre and startling as they must have seemed to his contemporaries.

It would be hard to produce a great Magritte exhibition, but just as difficult to put together a bad one. Although he had all the skills, Magritte’s paintings are wilfully pedestrian in their flat, expressionless surfaces. There are artists whose work only comes alive when seen on the gallery wall, but with Magritte one might as well be looking at a poster. He is a favourite artist among writers, philosophers and popstars – Paul McCartney bought his work, while Paul Simon wrote a song about him – but not for other artists. Magritte returned the indifference, never caring much for his fellow painters.

When he painted the sky, it was almost always pale blue with a few fluffy clouds. Whether he set out to depict a loaf of bread, an apple, a bottle, a chair, or a man in a bowler hat, it was pretty much the same thing. If he wanted to include a lion or a turtle, he’d find an image in a well-thumbed copy of the Larousse Illustré. He dealt in ‘types’ rather than oddities, relying on surprising combinations to get the reaction he desired.

Magritte hated to be called a “fantastic” painter. He insisted that he only depicted those things one saw in everyday life. He rejected the description of Surrealism as “pure psychic automatism”, popularised by the movement’s self-styled generalissimo, André Breton, preferring to work in a completely rational manner. It wasn’t his only disagreement with Breton, with whom he had a fractious relationship. It was partly a provincial issue, with Magritte and other Belgians feeling they were being treated like hillbillies by the sophisticated French. In response, they forged their own brand of Surrealism, more philosophical than the Parisian variety, shot through with deadpan humour.

The artist’s cultivation of the ordinary extended to the way he lived his life – a banal existence in the suburbs of Brussels, with his wife, Georgette – who had been his childhood sweetheart. He never had a studio, preferring to set up his easel in the lounge room. He dressed in sober suits and ties, even at home.

Throughout his career, Magritte was the most consistent of artists – aside from a burst of a few months in 1948, when he broke with the habits of a lifetime and created a series of deliberately ugly, luridly coloured paintings. In his so-called Vache series (the word means “cow” but is used as an expletive) he made an “Up yours!” gesture to French good taste, sold nothing, then reverted back to type. The show contains a selection of these aberrations, and they should still manage to raise a few eyebrows.

Magritte used to say he spent his time thinking rather than painting. He believed a work wasn’t truly finished until it had a title, usually supplied by literary friends such as Paul Nougé and Louis Scutenaire. Like Elvis, Magritte always had an entourage – writers by preference. He read Heidegger and Pascal, but preferred Nick Carter crime stories. His favourite book was Treasure Island. He wrote enough himself to fill a large volume – long letters, random notes, philosophical musings such as his Words and Images text (1929), displayed in this exhibition; an autobiographical lecture, even a detective story.

Magritte often claimed to be bored with painting - and it shows. It was the ideas behind the canvases that stirred his interest. He spoke about “problem” pictures, in which he set out to find solutions for the “problem” of the rose, or the door, or the egg, or the sea. The results were idiosyncratic, but to the artist they were as satisfying as finding an answer for a tricky piece of calculus.

Variation on sadness (1957) is one of those “problem” pictures. A chicken that appears to have just laid an egg looks quizzically at a boiled egg in an egg cup. It’s the old conundrum of the chicken and the egg, but the title imbues the scene with melancholy. We imagine the chook reflecting sadly upon the mysteries of life and death.

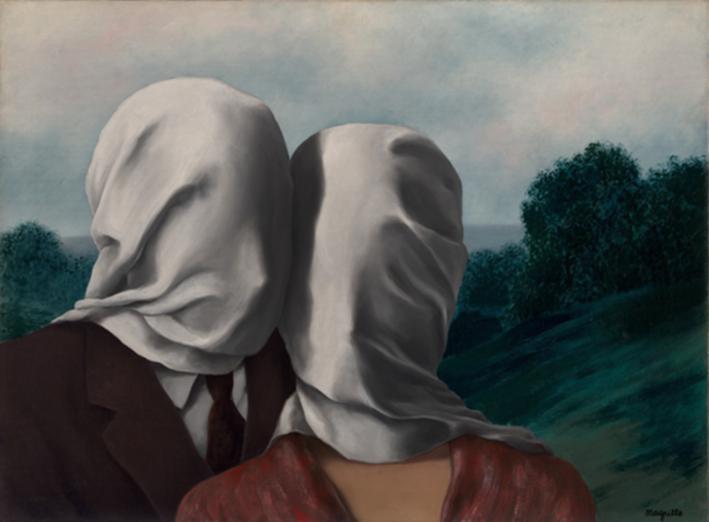

In The Lovers (1928), from the collection of the National Gallery of Australia, we see a man and a woman with their heads covered in shrouds. The title prompts us to think of “blind love”, or perhaps love and death. Magritte would ask the questions and leave his audience to come up with their own answers. He was adamant that his motifs should not be seen as “symbolic” or subjected to psychoanalytical interpretations. He painted concrete forms, drawn from everyday life, popular magazines or the encyclopaedia. “There is only one mystery,” he told a prying interviewer, “the world.”

Magritte

Art Gallery of NSW

Until 9 February 2025

John McDonald is one of Australia’s best-known and respected art critics, having spent more than 40 years reviewing visual arts, fashion, film, journals, and books. McDonald was the senior art critic for The Sydney Morning Herald for 41 years and was also well known for his weekly film column in that time. He has also worked as the Head of Australian Art at the National Gallery of Australia.