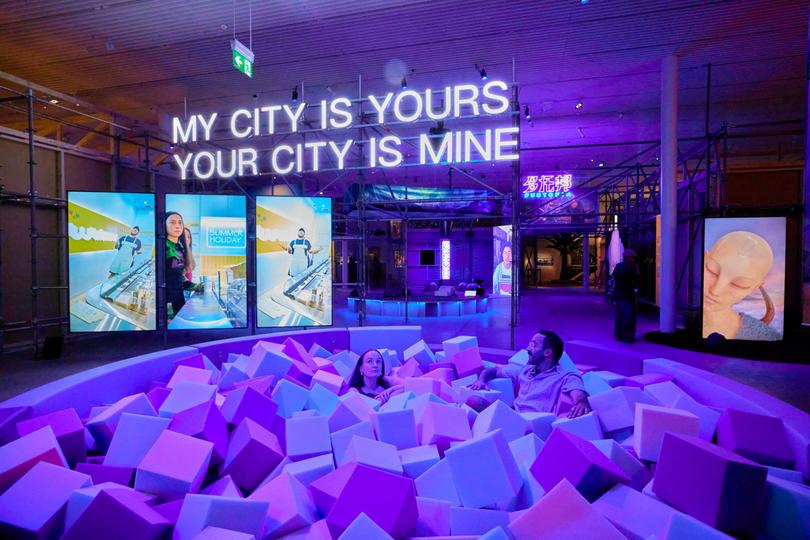

JOHN McDONALD: Cao Fei offers humour and humanity in post-Mao China in My City is Yours exhibition

After growing up in a China that modernised at a furious rate, Cao Fei uses her innovative art to scrutinise globalised techno-utopias and the consumer revolution with wit and warmth.

When China entered its age of reforms in the late 1980s there was an explosion of political art – sarcastic, angry, resentful of decades of hardship. This generation of artists had come to maturity at a time when the only acceptable art had been propaganda, with its relentless parade of smiling, heroic workers, soldiers and peasants. Artists had spent too many years feeling isolated and fearful, starved of creative freedom, and now they were getting their revenge.

The political art persisted even after the events of Tiananmen Square in June 1989, which put a clamp on nascent calls for democracy. There were sorrowful elegies for the Mao years, and Pop Art gags at the Great Helmsman’s expense. Most of this work was made for a western market, as Chinese collectors were virtually non-existent.

Cao Fei, whose show, My City is Yours, may be seen at the Art Gallery of NSW, is one of the supreme examples of what happened next. Born in 1978, the year in which Deng Xiaoping’s “open door” policy welcomed a tide of foreign investment, Cao grew up in a country hungry for everything the west had to offer - a time vividly described in Orville Schell’s chronicles of China in the 1980s. It’s also significant that she came from the southern city of Guangzhou, a centre for new business and industry.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Cao says she was obsessed with pop music, MTV, and Hollywood movies, which weren’t accessible to preceding generations. Cao has never known a China without a free market, advertising and a stock exchange. She wasn’t around to mourn Mao Zedong, who died in 1976. She had no traumatic memories of the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), her formative years being a period of huge energy and optimism.

Like most artists, Cao drew inspiration from the world around her, but it was a time of transition, as China modernised at a furious rate. She gravitated towards photography, film, performance and the emerging technology of the Internet, attracting attention with a short film called imbalance 257 (1999), made while she was still a student at the Guangzhou Academy. An anarchic exercise, with echoes of the French New Wave, it’s included in the AGNSW survey, along with almost everything else Cao has produced over the past 25 years.

Her works have grown progressively more ambitious as the technology has become more sophisticated. A high point was the creation of a virtual environment - RMB City (2007) – which incorporated many of the iconic buildings of China, past and present, as if they had been thrown into a shopping cart. Alongside such fantastic inventions she has forged two avatars for herself – China Tracy, a futuristic-looking heroine who plays the celebrity in RMB City; and Oz 2022, a bald, non-gender-specific apparition - half human, half octopus - who hovers around a new sky-city called Duotopia (2022).

One crucial aspect of these works is Cao’s willingness to embrace a globalised culture. RMB City may be packed with distinctively Chinese references, but it welcomes visitors from around the world, inviting them to contribute to a multicultural lifestyle. This is the utopian side of Cao’s work, born at a time of techno-optimism, when it was widely believed social media and the Internet would usher in a new era of international communication and understanding.

Nowadays we know this was no less of a fantasy than Herbert Marcuse’s predictions of the 1960s that the progress of technology would enable us to work only 2-3 days per week, leaving heaps of free time for self-education and the arts. Nobody alerted the bosses or the workers to these glorious possbilities.

Cao was sensitive to the cultural drift. Although she might have liked to believe technology was leading us to a better, more connected future, she could see that it had produced a globalised consumer inferno, a world of glaring inequalities in which the pursuit of wealth and fame outstripped any progressive political ideals.

She began to look behind the scenes at this consumer revolution. In her project, Whose utopia (2006) she undertook a residency at the OSRAM lighting factory in Foshan, an industrial district in the Pearl Delta. She asked the factory workers about their dreams and hobbies, getting them to publish a newspaper, form a rock band, and cultivate their special skills. In the accompanying film, the camera pans slowly around the factory, where we encounter one worker after another, singing, dancing, playing an instrument or doing Tai chi, while the wheels of industry turn in the background.

There’s a feeling of surreality in watching workers behave in this manner, absorbed in their own activities on the factory floor. It goes against all the time-honoured principles of taylorised efficiency, imbuing each worker with a personality. In place of anonymous drones, we see individuals. There’s a feeling of joy at this infiltration of personal pleasure into the workplace. Cao’s workers aren’t raging against the machine - they are letting it run in the background while they do their own thing.

It may be only a brief distraction from the routine of the assembly line, but it’s a precious moment. The film highlights another characteristic of Cao’s work – its irrepressible sense of humour. As essayist, Hou Hanru, puts it in the catalogue, “ultimately, she asserts that the most important thing is to have fun – the most pungent weapon to resist all ideological and economic dominations!”

One becomes so accustomed to artists making heavy-handed political statements that Cao’s oblique, up-tempo social critique can be completely disarming. When she revisits the factory theme in Asia One (2018), we find ourselves in a massive distribution centre in which consumer goods are being packed into boxes to be sent all over China. The film begins in a subdued style but evolves into a disco version of a model revolutionary opera, announcing a benign partnership between humans and machines. She also finds room for a giant inflatable octopus, a symbol of global capitalism which spreads its tentacles in all directions.

When a genuine streak of apocalyptic doom surfaces in Cao’s film, La Town (2014), it’s so eerie and playful that one watches in a trance. This strange ruin of a town constructed from tiny figures and model buildings, is a failed utopia, a place where the sun never shines, overrun with poverty and violence. A voiceover, inspired by the voice in Alain Resnais’s Hiroshima mon amour (1959), transforms it into a melancholy dreamscape.

Now in her 40s, Cao has lived through so many changes and social upheavals in China that she is already prey to nostalgia for familiar things that have disappeared. Chief among them is the old Hongxia Theatre, where she had a studio from 2015-20. One enters this exhibition through a facsimile of the Hongxia and exits via a reconstruction of the now-shuttered Marigold restaurant from Sydney’s Chinatown. These two immersive installations define our experience of the artist’s city, which is also our city. There’ll be many viewers, self-included, with memories of the Marigold.

Cao offsets the nostalgia with a series of Hip Hop videos, shot in Guangzhou, Fukuoka, New York and Sydney, in which ordinary people perform in extrovert fashion for the camera. An unusually personal note is struck by The Golden Wattle, an installation in honour of her late sister, Cao Xiaoyun, who lived in Sydney.

Curators, Cao Ying and Ruby Arrowsmith-Todd have assembled one of the most comprehensive collections of Cao’s work ever shown, and it can’t be taken in at a glance. By the time the Marigold installation looms you’ll feel overwhelmed by the sheer quantity of visual information you’ve absorbed. There are hours of film to be watched and detailed environments to be negotiated, courtesy of Charlotte Lafont-Hugo and Gilles Vanderstocken, of Beau Architects, Hong Kong, who have completely reinvented the unsatisfactory volumes of the AGNSW’s new building – now officially known as Naala Badu, a name that hasn’t proved catchy.

Despite the high-tech trimmings of so much of Cao’s output, what comes through most strongly in this vast survey is the human dimension. The artist may love to fly through space in the form of an avatar with octopus tentacles, but she is also a person who cares about those anonymous beings who work on assembly lines; who worries about the fabric of urban life being destroyed by rampant over-development, and the loss of innocence we find in so much popular culture.

It’s been noted on many occasions that pop culture is getting angrier, darker, scarier and nastier, partly as a reflection of audience preferences. It suggests a world in which the level of collective anxiety keeps rising, for obvious reasons. Cao is subject to the same anxieties as everybody else but what’s remarkable is her ability to keep finding ways to make work that’s vibrant, intelligent and entertaining. She demonstrates that bridging the gap between high and low culture need not be pure science fiction.

Cao Fei: My City is Yours

Art Gallery of NSW, Sydney

Until 13 April 2025